Blue Dollar

I grabbed Jenia by the wrist and urged her to hurry lest the old man at the currency exchange realize his error and come chasing after us. On the one hand, it felt like stealing and I should stop and say something. On the other, it felt like retribution for my stolen phone and the universe restoring balance.

I think the old man got confused, I told Jenia. He gave me double the money that he was supposed to.

We had just arrived at the border at Villazon and La Quiaca. Saying goodbye to Bolivia, I had just turned 200 bolivianos into close to 8,000 Argentinian pesos. In terms of purchasing power, that was a conversion of about $40 into $80. Suddenly, everything in Argentina was half-price.

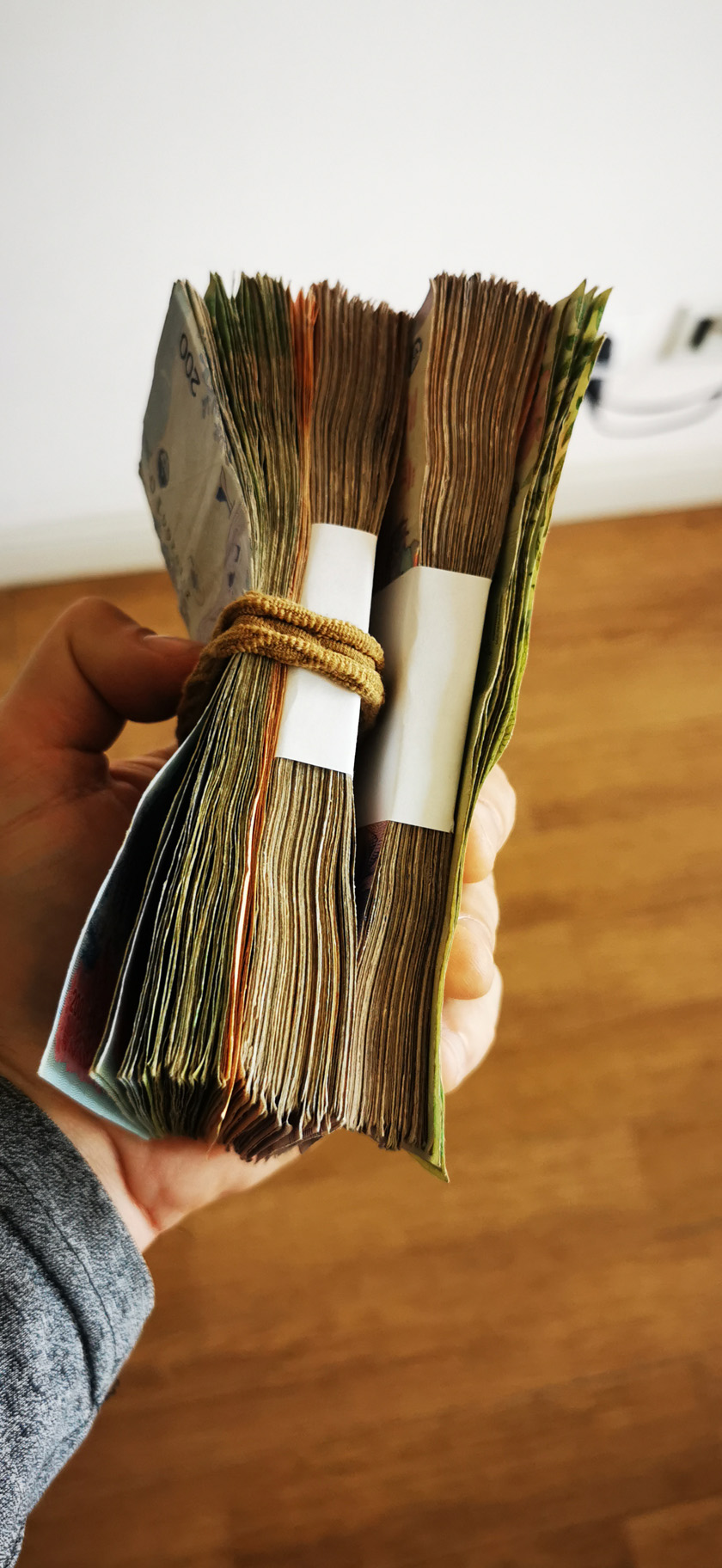

By the time we reached Salta, Jenia was going through the first sales period for her course. Her clientele of mostly ex-pat Russians scattered about the globe, because of the conflict in Ukraine, scrambled to find ways to send money to her accounts. One client, based in the Middle East, decided to send their payment for the course to Argentina using Western Union. Jenia was selling her course for about $500 USD which, according to currency converters at the time, was worth about 70,000 pesos. My legs felt queasy leaving the Western Union office with a gangster roll of cash amounting to close to $150,000 pesos. Walking through the streets of Salta, I felt as though we had a mark on our backs and that everyone who walked past us knew what we were carrying. We placed all of the money on the kitchen table in our apartment and could not believe what we were looking at. In over six months of travel, that was the best mood that I had seen Jenia.

By the time we reached Salta, Jenia was going through the first sales period for her course. Her clientele of mostly ex-pat Russians scattered about the globe, because of the conflict in Ukraine, scrambled to find ways to send money to her accounts. One client, based in the Middle East, decided to send their payment for the course to Argentina using Western Union. Jenia was selling her course for about $500 USD which, according to currency converters at the time, was worth about 70,000 pesos. My legs felt queasy leaving the Western Union office with a gangster roll of cash amounting to close to $150,000 pesos. Walking through the streets of Salta, I felt as though we had a mark on our backs and that everyone who walked past us knew what we were carrying. We placed all of the money on the kitchen table in our apartment and could not believe what we were looking at. In over six months of travel, that was the best mood that I had seen Jenia.

Can I buy you dinner? she asked with a cheeky grin.

The Western press had been reporting about the Argentine economy in free fall, paralyzed by rising inflation, and predicting that the country would soon become poor. Determining whether or not Argentina was an affordable country in which to travel was difficult to gauge. Unlike in other countries where the exchange and the value of goods are directly measurable against a certain standard, Argentina stood apart because of the gulf between the various methods of how to pay for goods.

In Salta, we visited a grocery store to load up on wine, deli meats, and other sundries. Naturally, as I had in every other country in South America, I charged everything to my card and we blew through $50 without blinking. Had we paid with cash, assuming we had acquired the cash off the exchange and not from an ATM, all of those groceries would have cost me only half the money.

I had heard whispers of the “blue dollar” during my first trip to Argentina but never discovered exactly what it was, how to acquire it, nor how the system worked. What I did notice during my first trip was how the country was cash obsessed even in the era of cards and online banking. Many businesses only accepted cash – effectivo, or plata, they called it. Acquiring blue dollars, or getting the blue rate, was sold to me as the best and most effective way to travel in Argentina. Currency exchanges around the world extract a fee for their services or provide a rate whereby they take a healthy slice to keep their operation profitable. At that time, the blue rate was regarded as a mysterious and illegal way to trade currencies on a blackened market, in the vein of money laundering, where the customer came out the winner in the exchange. From the point of view of the customer, it had to be a win-win because what currency exchange would trade at a loss? During my first visit, acquiring pesos at the blue rate required connections or was done hush-hush in back alleys and away from the prying eyes of police or regulatory authorities. Now, it was simply understood as part of daily life in Argentina and just the cost of doing business. Touts cooperated with official currency exchanges soliciting customers off the streets in plain sight. Some touts could offer a rate from the street and lead the customer to a hollowed-out residential apartment outfitted with nothing but a table, a calculator, and a counting machine. Like drug dealers, once you found the right source for cash, they were just a quick text message away ready to drop off cash to trusted customers.

United States dollars had long been (and still were) top dog trading at almost three times their value, but the cash-crazy Argentines were accepting paper money from just about anywhere at a rate that always benefitted the customer. I have a stunted education in economics, ‘spend less than you earn’ is the only truly valuable lesson I ever took away, but I could not help but wonder if the country’s obsession with paper money was in some way contributing to the current state of inflation and damaging the economy.

Understanding that cash exchanged into Argentine pesos was more valuable than money used by other means, the only obstacle left was to find ways to acquire cash to exchange. The experience at Western Union had taught Jenia and me a valuable lesson: besides being a way to send and receive money, Western Union is itself a currency exchange. We discovered the Western Union app where we set up hypothetical money sends and found that the expected rate of withdrawal factored the exchange in cash. Folks travelling to Argentina for a vacation can budget their length of stay, arrive with cash in hand, and live like kings and queens. We had been in South America for over six months, so we needed to organize a way to have money sent to us. I called home to Canada and explained what we had discovered.

It’s like creating money out of thin air, is how I described it to my mother.

My mother could visit a Western Union in Vancouver and send $100 to us in Argentina. She would pay a commission on top of the money sent but was far outweighed by the purchasing power from the cash we received. From there, the benefits only depended on how we spent our money. Gasoline that was being sold for $1.75 per litre at stations in Vancouver and 160 pesos in Argentina cost us only $0.75 in real money. A $10 bottle of wine suddenly cost only $4. The best $40 rib-eye we could find would cost us as little as $5 or $6.

Once we had tested this system, using Western Union to get cash became our preferred way to pay for things in Argentina. We would constantly assess the amount of cash we were carrying, what our needs were, and how long we would be staying in the country. When more cash was required, a call was made to Canada and more money was sent to Argentina. Each transfer gets an MTCN (Money Transfer Control Number) code that is shared by the person sending the money and used by the receiver to collect the money. A name is attached to the MTCN and all that is required to collect the money is a valid piece of ID that matches the name on the transfer.

Littered throughout Argentina are small shops branded as Pago Facil or Rapipago. These institutions are used by Argentinians to collect wages and stipends or pay electricity bills and traffic tickets. Most, but not all, have some kind of affiliation with Western Union. Depending on the size of the city or town, a particular Pago Facil could have a lineup around the corner the entire day or a limited amount of cash on hand. In the popular tourist destination of El Calafate, there was a single Western Union with a fixed window of operation for withdrawals between 9 am until they ran out of cash at 2 pm. There was also a hard cap on withdrawals up to $60,000 pesos per customer per day. The town was so inundated with tourists taking advantage of the scheme that they had shunted all of the Western Union withdrawals to the single location so that the other pay points could operate in peace. A lineup would form outside the office early in the morning and I met people claiming to have been waiting from as early as 4 am. If you are not careful you can blow through $60,000 pesos pretty quickly in Argentina and I met travellers for whom the lineup in El Calafate was a daily routine.

Making the best use of the blue dollar takes strategy. Smaller transfers had a higher percentage of money lost to commissions but a better guarantee that you would be able to collect your money. It also seemed wisest to only use cash on daily expenses like gasoline and food. We thought about covering every expense including accommodations with blue dollars but it involved cutting deals with every hotel or Airbnb host. They would readily accept American dollars but had less to gain if you paid in pesos.

We continually heard rumours of an economic crisis in Argentina that seemed invisible to our eyes. Locals continued to sit idly in city parks, drink mate, and dine out at restaurants and bars. Compared to the hardened grimaces of the austere locals in Peru and Bolivia, most Argentinians walked with a lightness and pride that we were unaccustomed to seeing in South America. Everyone we met complained of rising prices but this seemed to have little effect on behaviour. It is difficult to say what effect this strange system of subsidizing paper money is having on the country or whether the continuing crisis might eventually alter consumer behaviour. What is clear is that the blue dollar has hit the mainstream.