Nikkei

We had a lot to complain about in Peru. The sun rarely shined. Cities and towns were cramped and dusty and the traffic was chaotic. When the driving was done and we were settled, there seemed to be few outlets or spaces to simply enjoy our whereabouts and rarely did we arrive in a new city and consider it worth staying beyond a day or two. The sole area that Peru set itself apart in a positive way was its cuisine.

During the two months that we spent in Peru, whether at an upscale restaurant in Lima or Cusco, or a cheap roadside diner in a small town, a hearty and delicious meal was a guarantee. Not only are dishes enticing in concept but those responsible for the meal’s preparation come from a tradition that values the pleasure of enjoying a satisfying meal. The hallmark of any Peruvian meal is its combination of local ingredients in its preparation. Rice and potatoes are key staples, salty toasted corn (cancha) accompanies just about every meal, and there is a pervasive use of aji (spicy peppers), lime, and onions that brighten just about every dish.

Meals are accompanied by an array of tangy dipping sauces that both stand on their own or combine harmoniously into exciting new flavours that make every bite unique. Pollo Brasa (roasted chicken) is the quintessential example of this Peruvian culinary philosophy. Roasted chicken is such a universally loved meal that every culture across the world has developed its own particular take on the meal that incorporates its own local flavours and ingredients. The roasting of the chicken is ostensibly the same from country to country and where each version of the meal sets itself apart is in its gravies and sauces. In Peru, roasted chicken is served with three sauces: one white, one yellow, and one green. Each one is simultaneously soft and creamy as well as bright and tangy. It is a subtle but wholly unique, take on the dish.

Staple ingredients are also served in uncommon ways that subvert expectations and taste buds. Two popular spins on how to serve potatoes include causa and papas huancaina. Huancaina is a tangy yellow sauce with a base of spicy peppers and fresh creamy cheese that covers boiled potatoes and is served with black olives. Causa is mashed potatoes seasoned with lime and formed into patties and sandwiching shredded fish or chicken. As for rice, a popular dish is tacu tacu where leftover cooked rice is combined with beans and spices and fried into a cake.

Quinoa, the stereotypical staple of the Andes, also has its place but has become a modern, rather than traditional, ingredient. Peruvian chefs are not afraid to experiment and have incorporated Italian influences into its use with the widely popular dish, quinotto. Quinotto is a portmanteau combining quinoa and risotto where the traditional Italian use of arborio rice has been replaced by quinoa as the main ingredient. Smooth and creamy and a meal in its own right, just about every menu in Peru includes a quinotto option.

Although quinotto is an example of modern fusion, combining culinary traditions is embedded in Peruvian cuisine. Chinese food has spread itself across the globe and Peru is no exception. Chifas, restaurants specializing in this Peruvian-Chinese hybrid, can be found in every town serving chaufa and aeropuerto (Peruvian versions of Cantonese fried rice). Lomo Saltado, the Peruvian equivalent of a beef stir fry and is so popular that even traditional Peruvian restaurants will include it on their menus alongside aji de gallina and chicharron.

In Peru, the blending of culinary cultures finds its apotheosis in the tradition known as Nikkei. Nikkei refers to the immigrant population of Japanese who began settling in Peru in the 1880s, mostly along the northern coast to work in the sugar plantations. Nikkei blends together the philosophies of Japanese cuisine with local ingredients. Peru’s flagship dish, ceviche, the Latin American version of sushi, with its signature marinade leche de tigre, has been shaped over recent decades by Nikkei chefs into its modern version. The influence of Japanese immigrants on modern Peruvian cuisine cannot be understated and has threads that run throughout South America. From Colombia to Southern Patagonia, Peruvian restaurants are some of the most popular in any city, many of which market themselves specifically as serving Nikkei cuisine. Even within Peru, restaurants will distinguish themselves as serving comida norteña (northern cuisine), or Piurana (from the northern city of Piura) where these influences are most pronounced. Throughout Peru, to those who know, seeing Norteña or Piurana on a restaurant’s sign is an undeniable indicator of the food’s quality.

During our visit, two meals typified the breadth to which Japanese cuisine has emerged as a guiding influence in Peru.

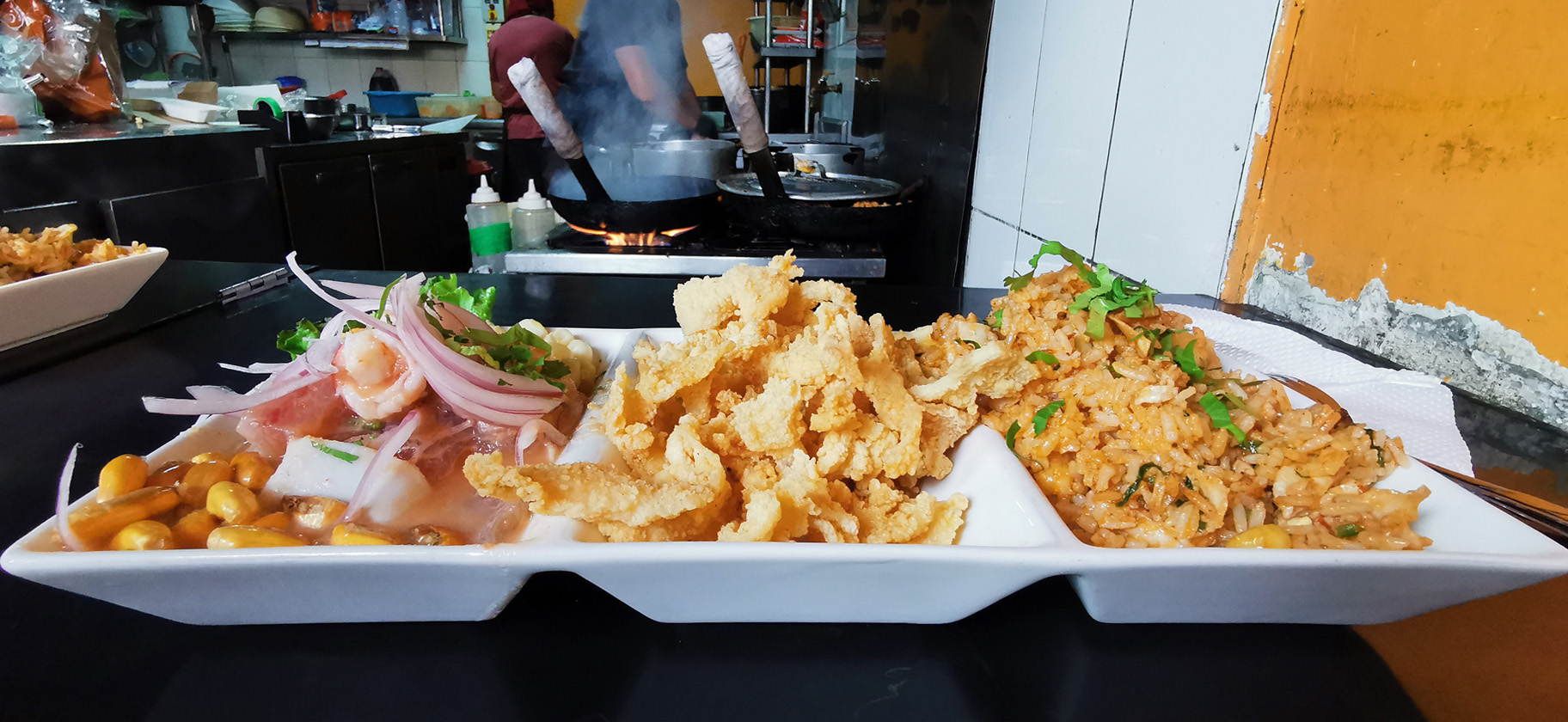

The first was a small hole in the wall in the bustling Surquillo district of Lima called Al Toke Pez. This tiny restaurant’s reputation had grown by word of mouth to such a point that there was a long lineup and only seating for about 15 people. Though they serve takeaway, there is a certain charm in its dark, understated, ambience. The restaurant’s proprietor, Toshi, was the son of an influential Japanese restaurateur whose restaurant had popularized Nikkei during the 1970s. With little interest in carrying on his father’s legacy, he moved to England to study in the pure sciences and earned his Ph.D. Upon returning to Peru, feeling somewhat lost, he decided to open a restaurant of his own design and more suited to his humble character. Incorporating the British idea of fish and chips (a hearty meal that was fast and cheap), highlighting Japanese flavours and pushing the Peruvian ideals of simplicity to the fore, Toshi popularized the combinado. The combinado, which can be found in restaurants throughout Peru, is three traditional dishes served side by side. It is the combination of ceviche, arroz con mariscos (seafood rice), and chicharrón de pescado (deep fried fish pieces). We came across the combinado several times during our trip but it achieved perfection at Al Toke Pez.

The first was a small hole in the wall in the bustling Surquillo district of Lima called Al Toke Pez. This tiny restaurant’s reputation had grown by word of mouth to such a point that there was a long lineup and only seating for about 15 people. Though they serve takeaway, there is a certain charm in its dark, understated, ambience. The restaurant’s proprietor, Toshi, was the son of an influential Japanese restaurateur whose restaurant had popularized Nikkei during the 1970s. With little interest in carrying on his father’s legacy, he moved to England to study in the pure sciences and earned his Ph.D. Upon returning to Peru, feeling somewhat lost, he decided to open a restaurant of his own design and more suited to his humble character. Incorporating the British idea of fish and chips (a hearty meal that was fast and cheap), highlighting Japanese flavours and pushing the Peruvian ideals of simplicity to the fore, Toshi popularized the combinado. The combinado, which can be found in restaurants throughout Peru, is three traditional dishes served side by side. It is the combination of ceviche, arroz con mariscos (seafood rice), and chicharrón de pescado (deep fried fish pieces). We came across the combinado several times during our trip but it achieved perfection at Al Toke Pez.

The second meal was at an upscale restaurant situated along Cusco’s Plaza Mayor called Limo. Limo’s menu feels more Japanese and features popular Japanese dishes like maki rolls, udon noodles, and gyozas. Borrowing from the Spanish tapas concept, plates are small and meant to be shared. Unlike the combinado that is meant to fill you up as much as it is meant to be delicious, great care has been put into controlling the flavours in every tiny morsel of each of Limo’s dishes. Each one is meant to be savoured in one or two slow and deliberate bites and, depending on what one orders, a vast array of flavours can be covered in a single meal. The experience and philosophy behind Al Toke Pez’s combinado is perfection in a single dish. On the other hand, the experience of Limo is about enjoying the journey that your palette travels over a series of hot and cold dishes that combine the array of savoury, spicy, sweet and sour.

Much the way an Asian restaurant in Mexico will make little cultural distinction when it serves Cantonese fried rice, Japanese sushi, Korean bulgogi, Vietnamese pho, or pad thai on the same menu, a Latin American restaurant in London is just as likely to serve Mexican tacos, Chilean empanadas, Peruvian ceviche, and lomo saltado alongside one another. Setting aside subtle regional variations, Peruvian cuisine is evolving a gestalt that has begun to set itself apart and challenge the heavy hitters of the world stage. Nikkei, and Peruvian cuisine more broadly, is setting itself up to become a vogue new culinary trend that is ready to export itself to globalized cities from London to Tokyo. In the decades to come, I expect I will be able to travel far beyond Peru’s borders and dip delectably prepared roasted chicken into pollo brasa’s distinctive sauce trio, and it won’t be long before the Americans, French, Turks, Indians, and Indonesians develop their own version of Toshi’s combinado.