Pub Talk – The Madness of the Imperial System of Weights and Measurements

I make it a point during all of my stops to put my workaday world aside for a few hours and visit a local pub with the purpose of sampling some of the local ales. Generally, I keep to myself and either write in my travel journal or read my book, but the character pubs I tend to spend time at have their set of regulars who recognize instantly that I don’t live around the corner. The further north I’ve travelled since arriving in Britain the more difficult I find it is to understand what people are talking about due their accent, but I was never so lost as when I struck up a conversation with a pair of couples a generation older than myself and the conversation somehow turned to the weights and measurements of the old Imperial System.

Remnants of the Imperial System exist today in most of Britain’s former colonies, including Canada, and even I’ve been raised to think of my height in feet and inches and my weight in pounds. But the metric system has taken root in most segments of society and my generation has been grandfathered in to purchasing petrol by the litre, adhering to a kilometre per hour speed limit, and deciding what clothes to wear depending on what the temperature reading is in degrees Celcius. In a backward sort of irony, the USA, despite their violent revolution, seems to be particularly keen on clinging to the old British system. In fact, they are the only first world economy to still use it. Moreover, along with Liberia and Myanmar, they are the only nations on Earth still exclusively using the Imperial System.

The Imperial System does have strong roots that older generations still cling to, like the whole feet and inches and pounds and ounces thing, but it is when one begins to explore some of the terms that are no longer in use that things get really interesting. It is impossible to design a way to explain how the system works in a logical way, for it is a system seemingly bereft of logic, so hold onto something and just try to keep up.

Money

The British still use the pound, having never adopted the Euro, and, in the case of its origins, it does refer to a weight as in the weight of silver. The term pound is not exclusive to Britain as many countries around the world refer to their currencies in pounds such as Egypt, Lebanon, and the Sudan, and the concepts of “weight” and currency have roots in other countries like with the old Spanish peseta, the peso of many Latino countries including Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Colombia and others, as well as the old Italian lira which translates literally to pound. Originally, the term pound referred to 240 silver pennies which would have been the weight of one pound in silver. Nowadays the price of silver, thanks to inflation, isn’t exactly one to one and would fetch you about 11 pounds sterling per ounce, or about 170 pounds sterling per actual pound of silver in weight. And that’s all fine and good, and nowadays you have a sensible hundred pence per pound, but it didn’t always use to be that way. At the end of the day all of these units of measurement add up to a certain amount of purchasing power and the pound today doesn’t buy what it did a hundred years ago. In fact, there are now 140 less pennies per pound than there were up until as recently as 1971. On February 15, 1971 the United Kingdom decided to decimalise their currencies scrapping their old system of 240 pennies per pound and replacing it with the current system of 100 pennies per pound. The divisions and the coinage get even more confusing. Pre-1971 the penny was divided into half-pennies (sensible) and farthings at a rate of 4 farthings to the penny (given the current use of the quarter, the farthing makes sense). Twelve pennies made a shilling (because of course), which was divisible into threepence (4 of which make a shilling) and sixpence (2 of which made a shilling), the math of which, though seemingly arbitrary, works out. There were 20 shillings to the pound for no particular reason, the florin was equivalent to the modern dime (one tenth of a pound), the half crown would have been worth the modern equivalent of 12.5 cents as there were 8 per pound as a full crown would have been equivalent to a quarter. Farthings themselves were further divisible into a half farthing and a quarter farthing and for some reason also a third farthing which seems about the equivalent of a three-dollar bill in its usefulness. Now hang on here for a second, in a wonderful twist, the coin that was in circulation that was equivalent to the pound wasn’t called “pound” but instead was referred to as a “sovereign” because common sense. At least that was the case from 1817, but before that you’d have been referring to a “guinea”, because of course.

Weight

Enough about money. Now the number 12 (remember that whole shilling thing) still exists as a divisible unit in several parts of society that it doesn’t seem totally outlandish for it to be used in modern measurements. The day is made up in sets of 12 hours, and the year is divided, if a little unevenly, into 12 months, and even in modern weights and measures the foot is divided into 12 inches. It is not as simple to calculate as the decimal system but there is a certain comfort in consistency with how ubiquitous it is. But when the imperial system decided to tackle weights they went off the rails – and just wait until we get to volume. Now using a pound as our starting point much as we did with money, let’s do it again with weight where one pound is sensibly divided into units called ounces of which there are 16 which seems absolutely just about right. The British then have another unit of weight called the stone… okay? So how many pounds to a stone should we expect? Ten would be the easiest to calculate, but no. Twelve might seem logical given how pervasive it is as a divisible in other measurements, but alas no. Okay, so a pound is divided into 16 ounces, so a stone must be, for consistency sake, 16 pounds, right? Sorry, no. In a maddening, but almost expected, twist of randomness the stone is made up of 14 pounds for what seems to me to be for no other reason than to make life slightly more challenging. Then there comes the Imperial hundredweight. It’s got to be one hundred pounds, right? Nope. Instead it’s 112 pounds (or 8 stones), because ‘yay’! Then, in a joyful romp through simplicity, the Imperial ton is made up of 20 hundredweights. So, to sum, that’s 16, 1, 14, 8, and 20 (or 160 if you prefer your stone to your hundredweight) – thankfully they had the good sense to stick to even numbers. I’ll let you mull over the fact that, besides the ounce, the pound was further divisible into the drachm (1/16 of an ounce) and the grain of which there are a very sensible meticulously counted 7000 grains to the pound.

Volume

Now we have a refreshing opportunity to come up for air from the confusion. First, let’s have similar, but still separate, measurements for liquid and dry volume (it’s really not much difference at all). The main unit (our volume equivalent to the pound) seems to be the pint. Pound, pint. Pint, pound. I can work with that. Now the pint, is divided into 20 units called the ounce just as the pound weight is divided into ounces… wait, no, that was sixteen… I mean the way the pound sterling is divided into shillings, only here it’s called ounces for the sake of consistency. You can also divide up the pint into gills (basically quarter pints) which can be divided into half gills or 2.5 ounces. Two pints make a quart and 4 quarts make a gallon, then there are 2 gallons to the peck and 4 gallons to the bushel and then, finally, 12 bushels to the box. Okay, that box thing isn’t a real thing, I made it up, but you may not have known that. And all this isn’t so bad until you have to think about the fact that part of the time from 1826 to 1971 these were the legal units that ran concurrently with the British apothecaries’ volume system which deals in minims, scruples, and drachms. It has its own symbols and logical system of divisions, but let’s just not go there. It stuck around for almost 150 years, but I didn’t want to go down the rabbit hole of finding out where its footprints might still be visible today.

Length

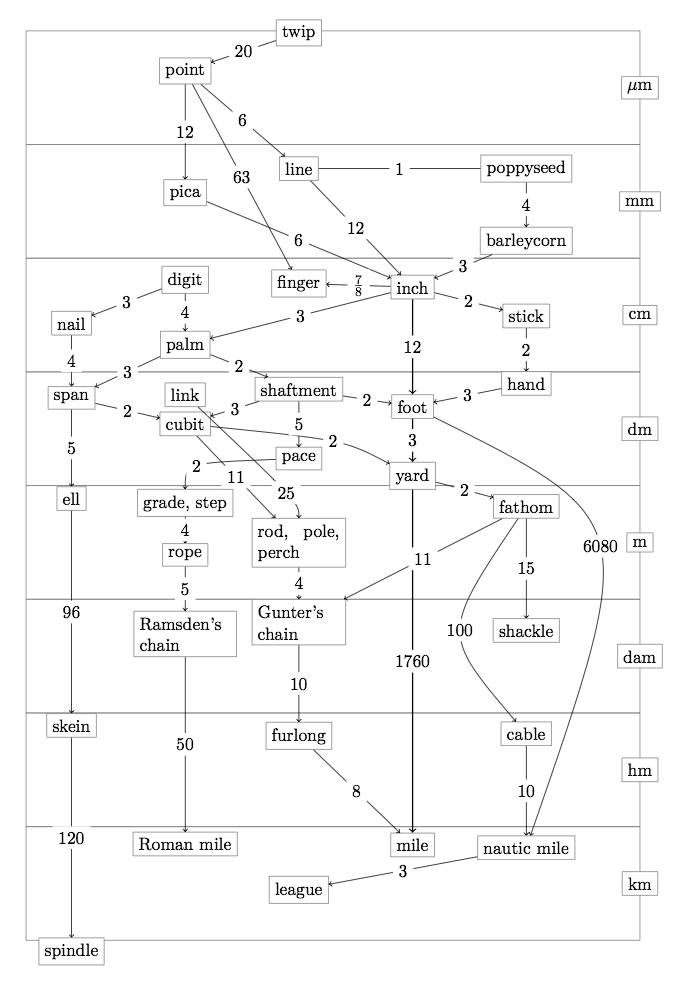

This is really where it all comes together. If you’ve felt confused up until now feel no fear as it’s all about to come together to fit into one neat and tidy little package. Our baseline (as we had with the pound and the pint) here is the foot which derives its origins from the average length of a man’s foot. To make things extra tricky, although the foot can act as our 1, unlike the pound or the pint, the foot wasn’t the standard for measurement at 1. Instead the standard 1 was the yard which, wait for it, was the length from King Henry I’s nose to the thumb of his outstretched arm. From there, sensibly, they just made sure that a foot would equal a third of that distance because we had been dividing everything else up into thirds at this point, so why not. Then we have our 12 inches per foot and, if you’re interested in dividing inches, there are 1000 thous (behold the seedlings of the metric system!). After that, what came first, the measurement or cricket, isn’t worth investigating, but after establishing the yard it was decided that the distance between widgets should be 22 of those yards – they couldn’t stop at 20 yards apparently – which is known as a chain. Ten chains (yay metric system!) equal a furlong, eight furlongs to the mile and three miles equal a league (a measurement which even the Americans have given up on.) For those keeping track, that’s 1000, 12, 3, 1, 22, 10, 8, 3 assuming your 1 is the yard. Now, of course, all of this only applies if you’re on land because at sea you are then dealing with the fathom (a comfortable 2.02667 yards) the cable (100 of those fathoms) and the nautical mile (10 of those cables) which, when calculated in actual distance, is 242.656 metres greater distance than the mile on land, or, thought of another the way, the distance of a mile on land is just under 87% the distance of a mile on water.

Now without getting into too much detail, these distances hold pretty well but there are some nuances when it comes to measuring area in which we deal in terms like perch, rood and acre. Working from largest to smallest, the acre (our 1 if you will) is measured as 1 furlong by 1 chain. The rood is defined by measuring 1 furlong by 1 rod. Now a rod, also known as the pole, comes from the Gunter’s survey unit of measurements where one rod equals 5 and a half yards. Yep. There are 25 links in that rod, of which a single link is calculated as 1/100 of that 22-yard chain or a very precise 7.92 inches. And let’s not forget that that perch is 1 rod by 1 rod. Tight.

By the end of my conversation with these two wonderful couples I could count myself as an expert in understanding the Imperial System. “It’s maddening you know,” one of them explained, “but I had to know it all once upon a time and I think it actually made my mind sharper overall”. It seems that perfecting the Imperial System made the old skull meat a little more extensible, but at least now we have Instagram.

If somehow by now you still feel as though you’re a novice when it comes to understanding the Imperial System I’m told that the chart below explains everything (about length anyway), you’ll notice that there are a bunch of terms in there that I didn’t even refer to – just go with it. Oh! And going back to measurements of length I forgot to mention that everything on land can be measured in feet and inches unless you are a horse. Horses are measured in hands for obvious reasons.