The Barbographer of Hamburg

“Today, our perception of the world is constructed by the .jpeg, the .pdf, and the .gif.”

Joachim looked at me with intense eyes and referenced Kant and Heidegger as he expounded on ideas of what is and what can be known, and the spaces that exist between reality and perception. The cultivation of our epilation was a modern detachment from our wildness and an expression meant to separate the human from our animal selves. As a philosopher, for Joachim, human hair was a symbol of this connection to our simian roots and one of our deepest connections to the animal kingdom. But as an artist, human hair was the ornamentation of a particular space and the richest decoration of the human canvas.

Joachim Jacob grew up in Bremen and had the opportunity to study art in Berlin in the 1980s but gave it up over concerns of the AIDS epidemic that was decimating the gay community at the time. Instead, he made a more conservative choice and stayed in Bremen and earned a diploma in biology where he would eventually earn a fellowship to pursue his doctorate in the United States of America. Joachim travelled to Arizona to meet with his professor and one of his old college friends from Bremen. When he saw his friend spending her days sitting for eight hours every day at a computer in a lab, he asked himself if this was really the life that he wanted. The final decision was made on a trip through one of Arizona’s blooming deserts where Joachim felt so inspired by the beauty of the landscape around him that he decided to pursue a life of art much to the chagrin of the professor who had accepted his doctorate proposal.

Joachim returned to Germany and continued to study and had his work shown in various vernissages around Bremen and other parts of the country, as well as earning an invitation to Québec to help with the design of a forest landscape in the Lac des Laurentides. Joachim has an interest in a variety of art styles including architecture, design, and ornamentation, but it is hair, and specifically beards as a subject, that remains the focus of his work.

Joachim returned to Germany and continued to study and had his work shown in various vernissages around Bremen and other parts of the country, as well as earning an invitation to Québec to help with the design of a forest landscape in the Lac des Laurentides. Joachim has an interest in a variety of art styles including architecture, design, and ornamentation, but it is hair, and specifically beards as a subject, that remains the focus of his work.

It was a bright and sunny day in Hamburg and I was sitting at a restaurant along the collanaden of Gustav-Mahler-Platz when a man on a bicycle stopped to ask me a question. I told him that I did not speak German at which he asked if I spoke French. This was how I met Joachim. He stopped when he saw me because he wanted to ask me if I would like to have my beard photographed. It seemed an odd request and my first instinct was that this was some sort of fetish thing, but he was genuinely kind and explained what he did and openly admitted that it was something that would probably sound strange to me. Over the years, I have learned that when anyone claims to be an artist the easiest thing to do to parse out whether or not they are legitimate is to ask to see some of their work. Joachim handed me a business card that described his business as part of the Institute for Discovery of Surfaces in the Barbography and Pelology Department. It sounded made up. But as someone who had invented their own job title, who was I to judge? He said that the website on the card was not a good place to go, but that if I sent him an email that he could send some samples of his work as attachments.

I was reluctant and skeptical, but after returning to my hotel at the end of the day and behind the safety and security of my computer screen, I decided that there was no harm in reaching out. Within a few minutes, Joachim’s reply came and immediately I could see that he was at least a genuine artist and not just a weirdo with a beard fetish.

Three years before meeting Joachim I travelled to Bilbao in the north of Spain. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao is one of the most famous architectural landmarks in the whole country and one of the foremost Modern Art museums in the world. It was here, in its grand hall, that I was first introduced to the work of Richard Serra and his torqued ellipses. When exploring the art world, very occasionally, as an enthusiast you get exposed to something or someone’s work, and they are able to pull you into their world and teach you how to see in a way you would never have discovered on your own. The bridge that they build transports you to their point of view. Pointillism and the work of Chuck Close altered my perception of sight and seeing through paint on canvas, but it was the work of Richard Serra that undid how I perceived space and the way in which we used walls and shapes to create and distort our sense of it. When I saw Joachim’s work for the first time, it was the influence of Richard Serra that I found the most striking.

I strolled out to the hipster neighbourhood of St. Pauli where Joachim lives just a few minutes away in nearby Altona with his partner Uwe. We had lunch and talked about philosophy and art and especially the human perception of hair; its removal and sculpting; where fashions come from and what they mean. There were no conclusions, only observations, of the trends we had each lived through from the moustachioed 1970s, the androgynous glam haircuts of the ‘80s, the clean-shaven ‘90s, the man bun of the early 2000s, to the manicured beards of today. We talked about the irony of men’s desire to retain a full head of hair into older age as a symbol of their male virility while simultaneously living through a period where bald men, such as Bruce Willis, Dwayne Johnson, Vin Diesel and Jason Statham, are cast into the most masculine of Hollywood roles and are revered for their masculinity as symbolized by their baldness. We also discussed the male gaze and its effect on the perception of feminine beauty from the point of view of both sexes. There has been an enduring knock-on effect of men seeking, and casting into categories, certain types of women, and women both conforming and rebelling against these various forms of social control. Everything from the tomboy haircut, to high heels, to bra-burning, to waxing, they all have their genesis in the male desire to separate the female sex from that same animal nature and elevate them to some unobtainable angelic ideal. It is an artistic trope that has persisted for centuries from the lithe and graceful curves of the sculpture of Venus de Milo to every 16th century Italian Renaissance depiction of Eve and reclining Venus, right through to every photo spread in Cosmopolitan and Glamour magazine. But for every convention, in the art world especially, there are rebels who have forced us to question the preconceived notions we inherit. Any visitor to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris will have taken note of Gustave Courbet’s provocative piece, L’Origine du Monde. The painting’s lewdness is designed to shock and is renowned for being one of the most seminal works of 19th century French Realism. It was Courbet’s decision to turn his back on the academic presentation of the female nude and shift the spotlight of a work of eroticism from the female form to the female genitalia in its most natural, and unshorn, state that most convincingly provokes us to question our ideas of eroticism and our animal nature. Courbet makes it clear that there has always been something linking hair with human sexuality from its colour, where on the body it is concentrated, how much of it there is, and how each individual treats what belongs to them. We have all been enculturated into a time and place where the answers to all of these small questions say something about us and our desires. Hair need not represent only our desire as concerns lust and sexuality, but can also represent our desires for power and wealth. One need look no further than ancient Egypt where the beard was the ultimate symbol of power as depicted in the hieroglyphs of pharaonic kings. When female pharaohs such as Hatshepsut, who reigned over Egypt in the 15th century BCE, are depicted in hieroglyphs they are similarly done so wearing a false beard as a symbol of their pharaonic status. In that place and at that time, to have a beard meant to rule the land.

I strolled out to the hipster neighbourhood of St. Pauli where Joachim lives just a few minutes away in nearby Altona with his partner Uwe. We had lunch and talked about philosophy and art and especially the human perception of hair; its removal and sculpting; where fashions come from and what they mean. There were no conclusions, only observations, of the trends we had each lived through from the moustachioed 1970s, the androgynous glam haircuts of the ‘80s, the clean-shaven ‘90s, the man bun of the early 2000s, to the manicured beards of today. We talked about the irony of men’s desire to retain a full head of hair into older age as a symbol of their male virility while simultaneously living through a period where bald men, such as Bruce Willis, Dwayne Johnson, Vin Diesel and Jason Statham, are cast into the most masculine of Hollywood roles and are revered for their masculinity as symbolized by their baldness. We also discussed the male gaze and its effect on the perception of feminine beauty from the point of view of both sexes. There has been an enduring knock-on effect of men seeking, and casting into categories, certain types of women, and women both conforming and rebelling against these various forms of social control. Everything from the tomboy haircut, to high heels, to bra-burning, to waxing, they all have their genesis in the male desire to separate the female sex from that same animal nature and elevate them to some unobtainable angelic ideal. It is an artistic trope that has persisted for centuries from the lithe and graceful curves of the sculpture of Venus de Milo to every 16th century Italian Renaissance depiction of Eve and reclining Venus, right through to every photo spread in Cosmopolitan and Glamour magazine. But for every convention, in the art world especially, there are rebels who have forced us to question the preconceived notions we inherit. Any visitor to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris will have taken note of Gustave Courbet’s provocative piece, L’Origine du Monde. The painting’s lewdness is designed to shock and is renowned for being one of the most seminal works of 19th century French Realism. It was Courbet’s decision to turn his back on the academic presentation of the female nude and shift the spotlight of a work of eroticism from the female form to the female genitalia in its most natural, and unshorn, state that most convincingly provokes us to question our ideas of eroticism and our animal nature. Courbet makes it clear that there has always been something linking hair with human sexuality from its colour, where on the body it is concentrated, how much of it there is, and how each individual treats what belongs to them. We have all been enculturated into a time and place where the answers to all of these small questions say something about us and our desires. Hair need not represent only our desire as concerns lust and sexuality, but can also represent our desires for power and wealth. One need look no further than ancient Egypt where the beard was the ultimate symbol of power as depicted in the hieroglyphs of pharaonic kings. When female pharaohs such as Hatshepsut, who reigned over Egypt in the 15th century BCE, are depicted in hieroglyphs they are similarly done so wearing a false beard as a symbol of their pharaonic status. In that place and at that time, to have a beard meant to rule the land.

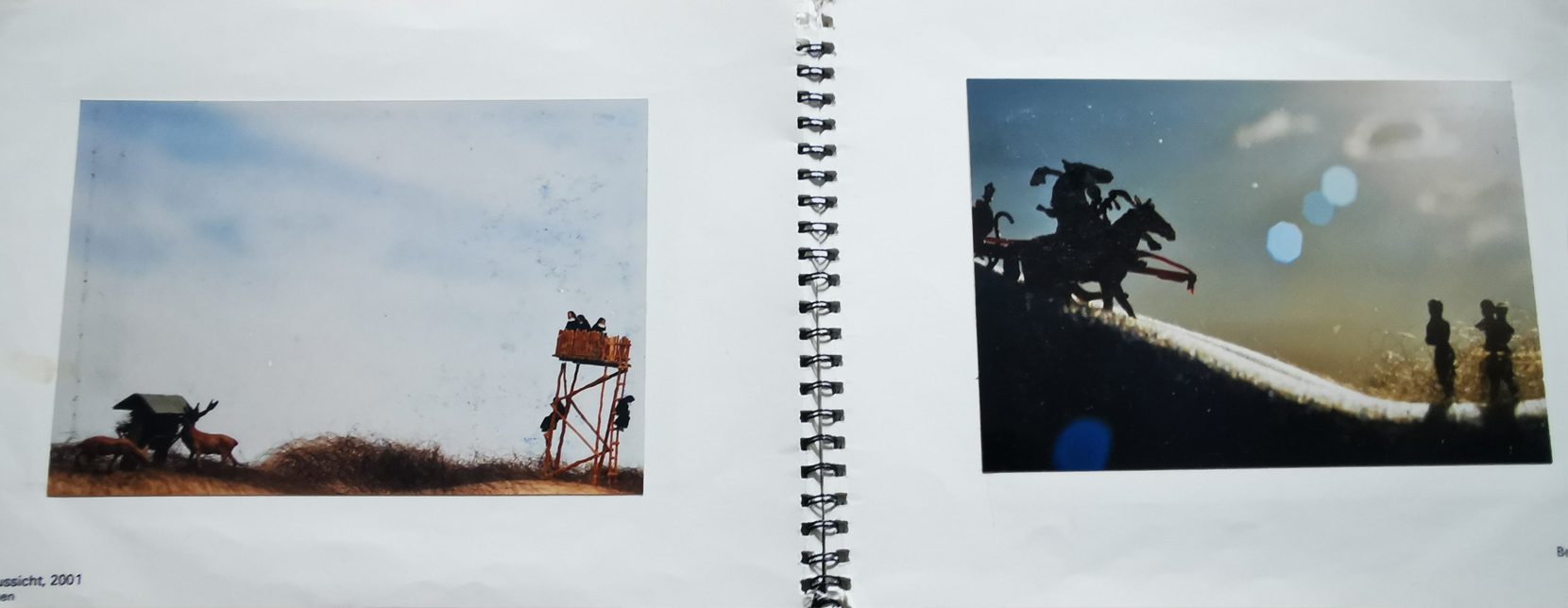

Joachim confronts many of these concepts in his work in a playful way by turning the human body and its hair into various landscapes where a hairy chin, inverted, might be a mountain slope down which skiers or young boys on toboggan slide; A man’s chest with full and lustrous hair and a cloudless sky in the background could instead be a dusty farm where tractors are busy turning soil and collecting grain; Or perhaps deer are grazing in a forest of a man’s curly pubic hair – the possibilities are endless.

Joachim confronts many of these concepts in his work in a playful way by turning the human body and its hair into various landscapes where a hairy chin, inverted, might be a mountain slope down which skiers or young boys on toboggan slide; A man’s chest with full and lustrous hair and a cloudless sky in the background could instead be a dusty farm where tractors are busy turning soil and collecting grain; Or perhaps deer are grazing in a forest of a man’s curly pubic hair – the possibilities are endless.

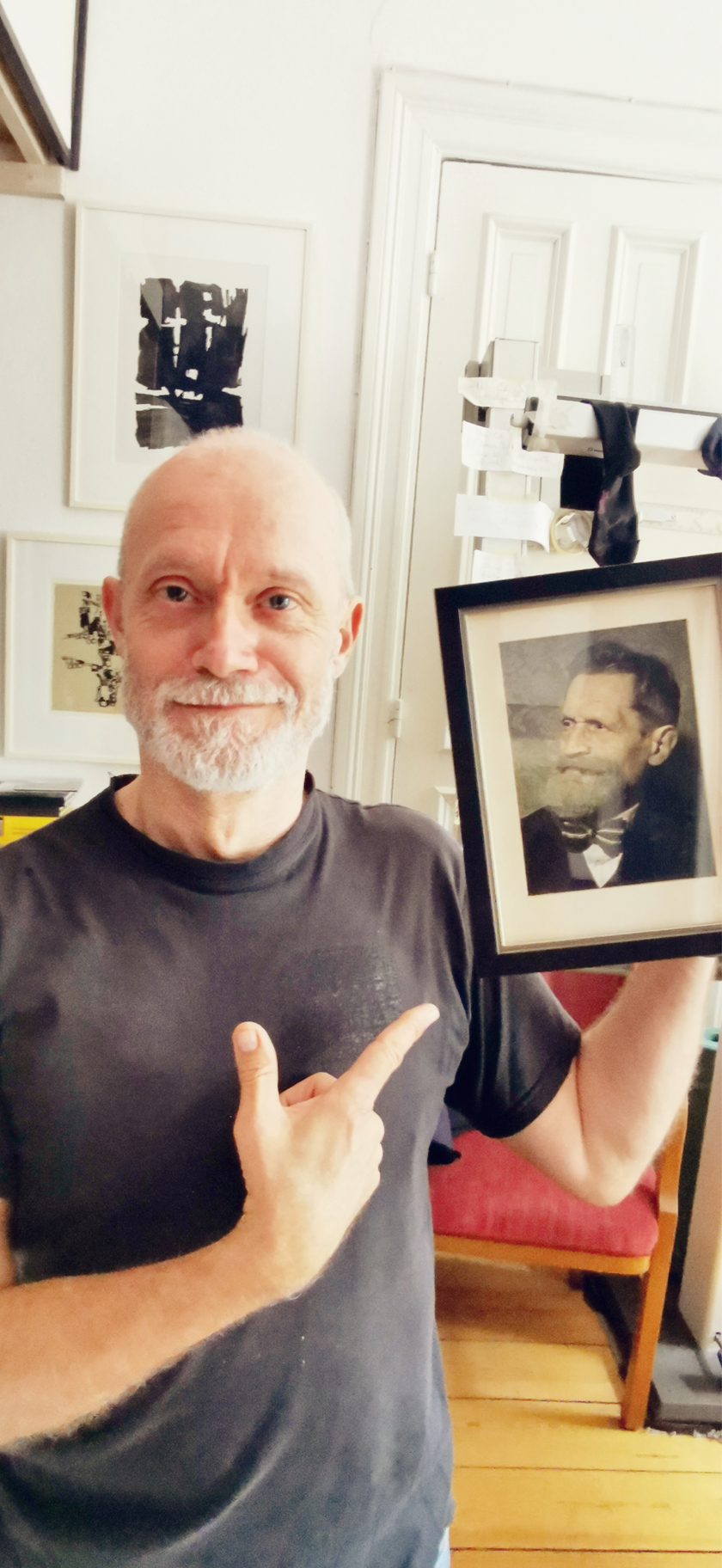

More than just a means of artistic expression, his appreciation for the bearded man has been Joachim’s great act of rebellion.Joachim showed me a very old photo of his grandfather for whom he had great admiration and who was the first person to inspire the beauty of the beard in his young artistic mind. Joachim’s father, on the other hand, was a very conservative man. While Joachim was growing up in the 1960s and 1970s his father, a devout Christian, used to bemoan the state of his country and blamed much of the internal political and social upheaval on the emerging generation of bearded hippies whom he believed to all be lazy, dope-smoking, ne’er-do-wells. For his father, there was an association between the look of long hair and a beard and the generational divide that irked him and made him untrusting of passing the torch onto these revolutionaries who thought so differently than he. Joachim described walking into his local church as a ten-year-old boy and seeing the German Christian depictions of Jesus and seeing this saviour with long hair, a beard, and teaching about love and change and couldn’t help but call out his father’s hypocrisy. How could his father revere and worship one man and his message while at the same time revile and denigrate another for the very reason that they looked similar and spread the same message? Further, as a young gay man, that archaic attitude was symbolic of the hypocrisy that continues to sustain much of the dogma of modern religions and alienate someone of his sexual orientation.

More than just a means of artistic expression, his appreciation for the bearded man has been Joachim’s great act of rebellion.Joachim showed me a very old photo of his grandfather for whom he had great admiration and who was the first person to inspire the beauty of the beard in his young artistic mind. Joachim’s father, on the other hand, was a very conservative man. While Joachim was growing up in the 1960s and 1970s his father, a devout Christian, used to bemoan the state of his country and blamed much of the internal political and social upheaval on the emerging generation of bearded hippies whom he believed to all be lazy, dope-smoking, ne’er-do-wells. For his father, there was an association between the look of long hair and a beard and the generational divide that irked him and made him untrusting of passing the torch onto these revolutionaries who thought so differently than he. Joachim described walking into his local church as a ten-year-old boy and seeing the German Christian depictions of Jesus and seeing this saviour with long hair, a beard, and teaching about love and change and couldn’t help but call out his father’s hypocrisy. How could his father revere and worship one man and his message while at the same time revile and denigrate another for the very reason that they looked similar and spread the same message? Further, as a young gay man, that archaic attitude was symbolic of the hypocrisy that continues to sustain much of the dogma of modern religions and alienate someone of his sexual orientation.

After getting to know Joachim, it was clear that his fondness for beards was not simply central to his art but was the locus around which his entire worldview had developed. It had not only influenced how he saw the world but how he showed the world to see. Whereas most men today grow their beards simply to complete their “look”, Joachim’s work reminds us that there is always more going on beneath the surface because hair on the human body is always saying something about us and the times in which we are living. Are we conforming? Are we rebels? Or, maybe we are just hypocrites?

Before parting company, there was still the question of whether my beard would ever make its way onto Joachim’s canvas. I figured, if somehow my beard could contribute to a better understanding of the connection between ourselves and the hair that grows on us, and perhaps steer us all in the direction of re-wilding even just a little bit, then I was never going to deny Joachim the opportunity to make use of it. We climbed onto the roof of his apartment building with all of Hamburg in view and where I stood completely still while he orbited around me snapping photos. What sort of creation Joachim will sculpt with the photos he took of me only he knows, but over the course of speaking with him that day he had pulled me into his world and built a bridge so that now when I gaze into the mirror I no longer see my beard as simply completing a look but a statement of me in this time and in this place.