The Darkest Day

The train out of Umeå was over an hour late and the sun had been setting in northern Sweden well before 2 pm for many days. By the time I arrived in Luleå, though it was just the early evening, it felt like the darkest hours of nighttime and I was exhausted from the day’s travel. Winter felt like it had finally arrived when I was in Sundsvall just five days earlier, and though little snow had accumulated, the air in Norbotten Province was cool and biting. There was no one at the Amber Hotel reception to greet me when I arrived and just a key card waiting at the front desk with my name and room number on it. I descended a winding staircase into the hotel basement and entered my room. It felt like a bit of a dungeon with but a small submarine-like window in the corner that let in little if any natural light. It was not the most welcoming of rooms, but the renovations were modern and the bed was comfortable and my stay was only for three nights.

The Arctic Circle is the northernmost point at which the centre of the noon sun is visible on the day of the winter solstice which means that towns north of the Arctic Circle experience a day, or days, of total darkness every 21st of December. My objective since arriving in Scandinavia was to cross from Sweden into Finland via the Haparanda/Tornio crossing where the Torne river empties into the Gulf of Bothnia and then travel southward through the Baltic states. I had conceived the idea of crossing the Arctic circle for the solstice shortly after I had returned to Sweden from Norway and, with all of the uncertainty when crossing borders, I wanted to give myself plenty of time to assess the situation at the border in order to be well prepared for any covid-related restrictions they might enforce. A day of total darkness might not be on everybody’s bucket list but, travelling in search of winter, the shortest day that I would ever experience seemed as intriguing an objective as any. While travelling through Karlstad and Stockholm I spent hours researching routes and accommodations in both Sweden and Finland and found that there were far more, and far more affordable, options in Finland. However, there were no transit routes into Finland from Sweden as there had been with Norway and all bus routes through the northern border stopped at Haparanda. I had found a quaint looking Airbnb in a little village called Kalix not too far from Haparanda and figured that I would go to the trouble to travel to the border and ask questions. Arriving in Luleå on the 1st of December, I figured that giving myself almost 3 solid weeks until the solstice was plenty of time to figure out both how I was going to cross and how I was going to get up north of the Arctic Circle.

Brittmarie lives just outside Umeå’s town centre in a cute little house a short walk from the river. In her early seventies, her husband passed away a few years ago and she decided to open her guestroom to travellers as a way to add a little extra income to her pensions. She is a kind and caring woman who goes to great lengths to make her guests feel comfortable and welcome in her home. In my room, there was a little desk where I could work and Elvis, her kitty-cat, was always curious and underfoot. In the mornings, Brittmarie would prepare a huge breakfast with ham and soft-boiled eggs, yogurt and muesli, and freshly squeezed orange juice with ginger. On my second day in Umeå, she mentioned that she sensed that she may have caught a cold and, to be safe, would take a rapid covid-test to be able to rule it out. She had demonstrated a sense of caution from the moment I had booked her accommodation, but with this added element of concern, we decided to keep an even greater distance from one another for my final night’s stay. The following day, her son drove by the house to grab her sample and take it off to the lab and I checked out and continued my journey north.

When I woke in Luleå after my late arrival the previous day, there was optimism in the air and a swing in my step. Though we were losing more daylight due to the season, for the brief time that the sun was out it was magnificent. Luleå town centre sits on a peninsula that juts out into the river and, during these cold days, it had frozen over which brought skaters out into the middle of the ice carving tracks through the reflective orange twilight of the sunrise and sunset that are never broken by the day. But for my winter jacket that I had brought all the way from Canada, I still hadn’t suffered enough through winter temperatures to have outfitted myself with proper winter clothes but I was beginning to sense that it was almost time. I needed to keep my hands in my jacket pockets to keep from freezing and I could feel the tickle of the frosty air making my nose run. I could see my breath in the cold air and I found myself clearing my throat during my entire walk on the pedestrian walkway along the perimeter of the town. There was only about 4 hours of sunlight that day and I made sure that I was outside for all of them, but when the sun set it was time to return to my little dungeon in the basement of the Amber Hotel and get to work.

There was a lot on my plate that day. Besides the slate of deliverables my clients were expecting, I needed to figure out how to get to Finland and concoct some kind of plan of what I would do when I actually got there. People on the east coast of Canada and the US were just beginning their workdays and messages started to come in looking for news on various projects or updating me on the status of various other things and cutting into the time that I actually needed to complete the items on my to-do list. I was starting to feel a little overwhelmed and brewed myself up a cup of tea to help me relax and settle into the afternoon.

I walked over 20,000 steps that day and was beginning to feel like I would rather just lie down and rest than sit at this teeny-tiny little desk in my dungeon working the afternoon away. It was seeming like a gruelling workday and I was going through the motions and editing on instinct, trying to stay on top of it all, and responding to the alerts as they came in. Suddenly, there was a buzz on my phone and instead of a message from a client, it was a message from Brittmarie over 300 kilometres back down south in Umeå. She had tested positive for coronavirus.

Having come in contact with someone who had tested positive, I knew that I had a responsibility not to spread the virus if I also had it and that meant quarantining and getting a test. I immediately cancelled my booking in Kalix and extended my stay in the dungeon for five more nights. At the time, I was still attributing the tickle in my throat to the cold weather and my half-hearted work effort to the 10 kilometres I had covered exploring Luleå. I figured if I could get a test and it came up negative that I could be on my way with not too much of a setback to my plans and still with plenty of time to enter Finland and head up to the Arctic Circle.

That was a difficult night.

I was sick. Though the probability was high that I had contracted covid from Brittmarie in Umeå, the only way to make it certain was with a positive PCR test. I reached out to a friend who works in London for the NHS and since the start of the pandemic had been providing support to patients in the UK. She advised me to manage symptoms by taking paracetamol and ibuprofen and by staying hydrated. Bless her, but she knew too much. They say that if you give a man a hammer all he will see is a nail and so she went on. She had been working with the sickest of the sick including thousands who had succumbed to the effects of the virus and she advised me that the critical period is between 7 and 10 days from the first symptoms when patients often start to rally and see symptoms improve only to then completely U-turn and end up in the hospital with complications.

I still had not seen a single person who worked at the Amber Hotel but they had a telephone number and I thought it best that I should call and see what kind of assistance they could provide. There was little. Not only did the receptionist who responded have few answers as to how to go about getting tested in their town but they also seemed little concerned that they had a health hazard now stowed away in the bowels of their hotel. How was I even going to get food? I would have been happy to pay them extra money to ensure that I didn’t starve, but they had a “we-just-don’t-do-that” sort of attitude. I had found Swedes not only friendly but warm and inviting compared to their Scandinavian neighbours. But now, at my most fragile, from the people most in the position to be helpful, I was encountering a rare form of unexpected and next-level indifference.

I could barely move or get out of bed the entire day. I moped. I slept. I tried to work, but could not muster enough energy or concentrate for more than a few minutes. I left the hotel only once to stumble into the streets to a pizza shop to get takeaway while waiting out in the cold while it was being prepared. I had Netflix running most of the day but couldn’t stay awake even through a single episode of Community. The day was a write-off and by the end of it, though now certain I was sick with covid, I was no closer to proving it or knowing what to do if my condition worsened. The one thing I did accomplish (if one could even call it an accomplishment) was I informed my mother of the situation. Her face melted when I broke the news like I had been handed a death sentence. I reminded her that most people who get the virus do, in fact, survive. I was still relatively young and healthy with no underlying risk factors and it was more than likely that I would be just fine. Still, in the way that we all see ourselves as unique and special, I could not shake the idea that there was the possibility that I could be one of the exceptions.

That second night was the worst.

I had slept most of the day but was exhausted and somehow I couldn’t really sleep. By 2 am I was wired though barely able to move and soaked through with sweat. All of that moisture felt cold against my skin as I shivered completely unable to handle the swings in my internal temperature. The sheets from the pillow where my head had laid to the tip of the bed where my feet had been were sopping wet. Happily, the Swedes expect two people in a double bed and provide two sets of covers. The bed also had a thin blanket as a cover which I draped over the wet sheets so that I could now at least lie on something dry and I tossed the duvet into a corner of the room and would now use the one from the other side of the bed. I had to change all of my clothes. I grabbed my pyjamas and my t-shirt and my underwear and dropped them to the floor. Even on the carpeted floor, they made a heavy and damp slapping sound when they fell. Had I the strength, I could have wrung a bucket full of water from them and I have pulled clothes from a washing machine less saturated with wet than what I had worn that night. I slept in fits and starts oscillating between feeling like I was freezing and needing to cover up or feeling like I was about to overheat or spontaneously combust. All the while, the lion’s share of my mental energy was spent thinking that, no matter what, I could not allow myself to sweat onto this set of bed covers because this was all I had.

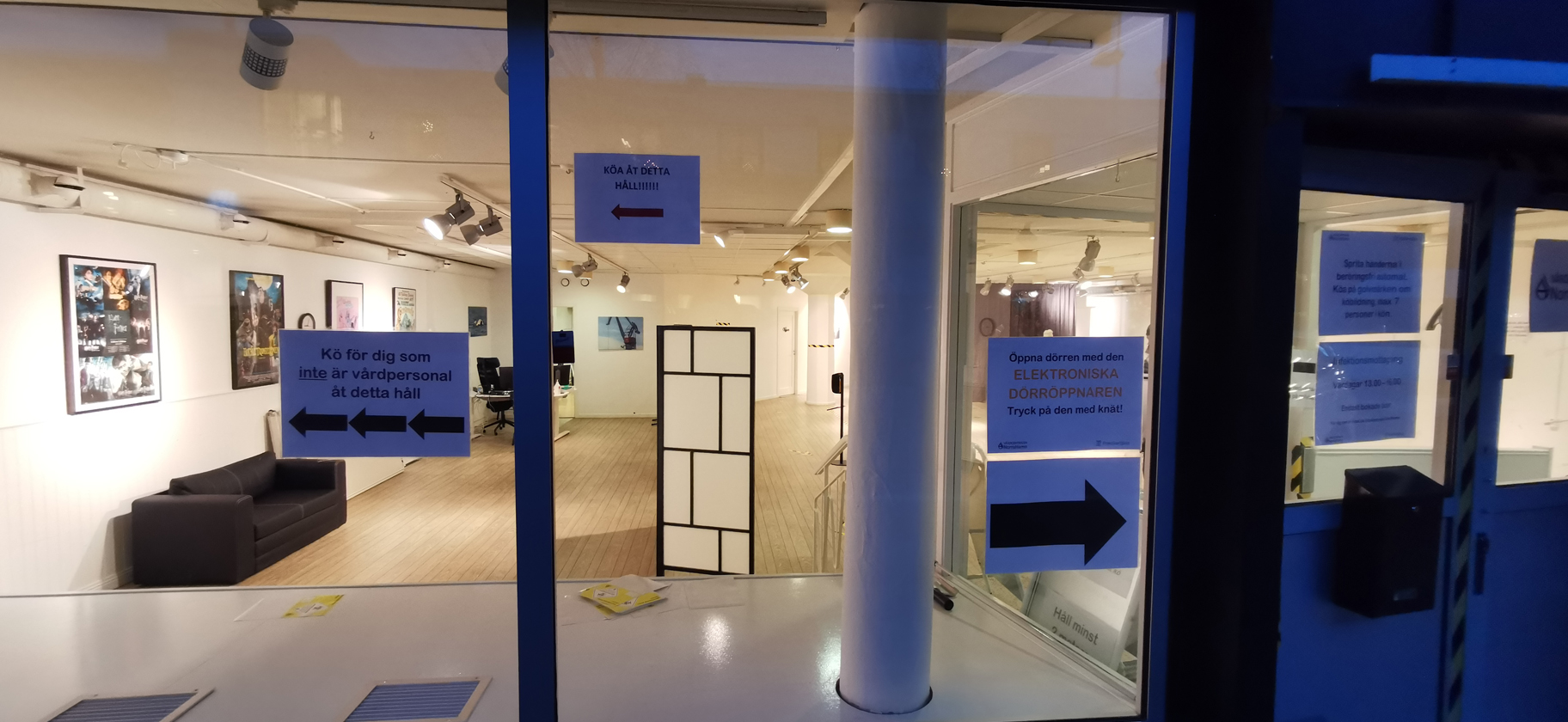

A brand new day brought fresh pain and suffering but in my few waking hours I was able to get information from Sweden’s 1177 online health service and located a clinic not too far away that did walk-in covid testing between 8:30 and 11:00 am. There was no difference between day or night for me now and it was simply about able or not able. As soon as I was able I headed out to the clinic.  It was not so much a clinic as an old storefront that they had repurposed just to keep the potentially sick people away from the hospitals. Though I did not have a Swedish health services card or residency status they only asked me for my driver’s license so that they could open a file on me and then administered the test first by probing my nasal cavity and by also taking a cheek swab. We knew the result already and I was just looking for confirmation. They were efficient and they were, above all, kind. They also now knew that I was ill, had information on where I was staying, and gave me information on what to do while I waited for my result and how to respond if my condition worsened. Normally, they would reach out by phone should someone test positive, but because I was using a prepaid phone card I could make calls but not receive them. I also did not trust the hotel to relay any messages to me, so to get the results, I would need to return in 3 to 7 days. It was such a small thing and I couldn’t have been gone from my little dungeon for more than an hour, but getting tested felt like I had taken a massive positive step forward in my recovery.

It was not so much a clinic as an old storefront that they had repurposed just to keep the potentially sick people away from the hospitals. Though I did not have a Swedish health services card or residency status they only asked me for my driver’s license so that they could open a file on me and then administered the test first by probing my nasal cavity and by also taking a cheek swab. We knew the result already and I was just looking for confirmation. They were efficient and they were, above all, kind. They also now knew that I was ill, had information on where I was staying, and gave me information on what to do while I waited for my result and how to respond if my condition worsened. Normally, they would reach out by phone should someone test positive, but because I was using a prepaid phone card I could make calls but not receive them. I also did not trust the hotel to relay any messages to me, so to get the results, I would need to return in 3 to 7 days. It was such a small thing and I couldn’t have been gone from my little dungeon for more than an hour, but getting tested felt like I had taken a massive positive step forward in my recovery.

It was a short walk, no more than a kilometre round trip, from my hotel to the testing centre. The weather in Luleå had warmed and the snow was beginning to turn to slush but it still felt like winter. The sun was rising for a short time each day at this latitude but darkness loomed over the city as its rays could not penetrate the thick clouds that had gathered in the sky. I was concerned about the effort involved, but being outside, and even just standing, felt like a relief from the agony I felt while lying in bed. Common sense suggests that when one is feeling sick that the best remedy is to stay in bed and get plenty of rest. But in the 48 hours I had been suffering with fever from the covid, I had discovered that it is during those periods of rest where the virus finds you. The virus wants you to be weak. It wants you lying down and off your guard. After returning to my dungeon, though careful not to overexert myself, I spent most of the day pacing the 4 steps from my bed to the door. Spanish clementines were in season and I had stocked up, so I would walk for 10 minutes and then stop and have an orange. I would lie on the bed and watch a show for 30 minutes, then get up and pace between the bed and the door again, and then stop and have an orange. That was my life for two whole days.

In the fullest fury of the illness, I figured out how to manage my symptoms with the medicines. The key dose was the paracetamol right before bed to lower the fever for long enough to actually sleep. With nothing to do, time stretched on making an hour seem like an entire day. In those bleak hours unable to sleep yet unable to keep my eyes open or concentrate my mind wandered off to all of those simple pleasures that I had left behind, that I never thought about when I was well, and that now seemed so far away and the only things I wanted to see.

I thought of the floor to ceiling windows on the sliding doors that lead to the balcony of my old apartment in Vancouver’s West End. They look out toward the mountains on the north shore that hover over the Georgia Strait and English Bay. Every morning, when the sun lights up the sky, I pull the sheets off of the bed whose lumps conform to all of my misaligned joints and fire up the Bialetti to brew myself a cup of coffee. Heading south out of the door of my building through the rain, I have to hop off of the sidewalk and into the road along Nelson for a block where the puddles gather in the cratered cobbles between Bute and Thurlow. Depending on how busy I am and what’s on, maybe I’d blow off work for a little while and head over to Scotia Bank Theatre for a matinee. I might have leftovers sitting on the stove, but the porchetta sandwich from Meat & Bread on West Pender is one of the finest lunches on the planet and whenever noon approaches it calls out its siren song. Fujiya is right across the street, though, and maybe I feel like some karaage or a California roll. Brushing past the holly hedges outside of the apartment complexes and heritage houses on Barclay, I always have the option of taking a casual stroll through Stanley Park. The geese and the mallards hang out by the Lost Lagoon all year round and just the crunching sound of the stones on the path sends a comforting tingle up my spine. If you have a moment to watch the sparkles on the water between English Bay and Sunset Beach life is good. There are benches by the Inukshuk and one in particular stares out due west past Kitsilano where, on a clear day, you can make out the line of islands in the channel. In the afternoon, when the sun begins to creep toward the horizon, it can be so bright that you need to tilt your head south toward the Burrard Bridge and Granville Island to dampen the glare. Cool winds ride along the fronts of air coming off the mountains in the east and they travel through the Fraser Valley all the way to the beaches and harbours in the city. Those breezes bring up that briny umami stink of the sea that is somehow both a little unpleasant and delicious as you walk along the seawall. It’s a steep uphill climb on Jervis up to Davie Street where I can stop in at the European Deli for some sliced cold cuts, pistachios and Turkish delight and where even in such a big city they recognize me. There is a lot of traffic running along Burrard between Davie past St. Paul’s hospital down to West Georgia and there are always a few drug-addled patients out in front who have wandered off and that loiter near one of the city’s communal gardens. If you close your eyes and can filter out all of the noise of the city, even in winter, you can make out the sound of birds chirping. It is big city living with everything you can want or need just a few steps away. It was comfortable and quaint and in those moments in the darkness, I wondered why I had traded that for the torture chamber I was now living in.

In the suburbs of Montreal where I grew up, I thought back to those winter nights as a teenager coming off the train from Montreal West when the sun had already set and escaping down into the basement to watch reruns of Cheers and The Simpsons. My family would sit at our dining room table and eat together just about every night and ever since I was old enough to reach the table, one of my jobs was to set it for the nightly supper. I grew up with my mom insisting on things that as a kid seemed frivolous like placemats, napkin holders, and lit candles. Now I understand better that those little routines were the signs that she and my father were not at work, that my brother and I were not at school, and that the whole family could just be together. It was what she had always wanted since she was a little girl – to have children and raise a family, and insisting on the presence of those small symbols like cloth placemats, napkin holders, and candles were the flowering of the seeds of her own youthful dreams as they were the pollen seeking fertile soil in the futures of her children. Some years ago, my mother insisted on a dinner of just my father and my brother and me, no girlfriends or extended family, as a gift to her for her birthday. We enjoyed a lovely quiet candlelit supper at Seasons in the Park in Vancouver 35 years and some on from our first (and for probably the first time in well over a decade) but it was the last with just the four of us like when we were growing up in our little house in Baie d’Urfé. You only get so many dinners together, and so many of them are eaten in haste coming from or on the way to some activity or obligation. Alone in my dungeon, chewing into my third takeaway pizza in four days, I craved any familiar face to sit with me with proper placemats, napkin holders, and candles and have supper and tell me everything was going to be alright. I was coping with the fever and the symptoms well enough but I could not shake the idea that things might get worse. And if my condition was going to get worse and I would need to be hospitalized, I begged for it all to start as soon as possible because waiting for it to happen was becoming intolerable to my psyche.

Every so often I would pick up my phone just to check what time it was. I had scrutinized every decision I had ever made; I had apologized in my mind to all of the people I had ever wronged; I had relived the near misses of every attempt on goal in every match I had ever played; I had rewritten all the run-on sentences from every essay I had ever penned; I had conceived of a perfect icebreaker for every romantic situation I had ever let slip away; I had composed marvellously insightful critiques of every novel, film, and piece of music I had ever read, seen or heard; and I had ranked from best to worst every meal I had ever eaten. And in that time, having subjected every subtle detail of my life to a thorough review, I could see that no more than 10 minutes had passed since the last time I checked the time. My brain was so fogged up that it required every ounce of my mental energy to instruct my finger to not only locate a light switch but also to turn it on – something that normally I could easily do just on instinct, but now it required actual effort. I would have conversations with myself, full two-party dialogues, about the importance of drinking water. My computer sat on the bed playing an unending stream of Netflix shows while I writhed around in the sheets unable to sleep but not really able to stay awake either. I could hear Sam asking Frodo if he could remember the shire and the fact that, though they were standing in the shadow of Mount Doom, back in that shire they’d be having the first of the strawberries with cream. That’s when I just let go and realized that the chasm between not being afraid to die and not wanting to die is wider than one imagines.

Enough of this! For almost a year I, along with the whole world, had been fed a steady diet of the virus is death, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had said as much back in April. I was a smart guy. I could sift through the statistics and see that the virus claimed the lives of 2% of cases. That is high by epidemiological standards, but put me in a room with 49 other people and I like my chances. Those most likely to have adverse reactions are the elderly or individuals with underlying conditions like heart disease and diabetes. Still, I have the steady drip from the news media to remind me that anyone could die from the virus, even me. Every day, the scientific and medical communities were developing new treatments and ways to fight the virus – a vaccine was even on its way – but I also had the news media reminding me that every day the virus was mutating and becoming more virulent and finding new and inventive ways to outsmart us. The climate crisis seemed to have taken a backseat on the list of worldwide concerns. Though police violence and the race issue in the US was still making headlines, there had not been reports of a mass shooting at an American high school in months. Maybe now was the time to discuss gun laws and refinements to the second amendment. But who wants to listen to the guy who is lying face down in his tear-soaked pillow and suffering through that tiny inkling in his conscience that he might not get to hug his mom again? I had to accept responsibility for getting sick. I knew the risks when I decided to travel and how my lifestyle increased my potential exposure. Friends, family, and acquaintances aware of my abhorrence of the lockdown measures many countries had been living through might even think to themselves that contracting the virus was just my comeuppance. Irrepressible amounts of schadenfreude permeated coverage of public events that flouted common sense covid restrictions and the resulting uptick in confirmed cases with little regard for tabulating the unknown thousands who strictly adhered to every suggested protocol and still fell ill. There I was cooped up in my dungeon panicking over a problem that has not presented itself and rendered incapacitated by the 2% chance that it might. That 2% falls to far less when you consider that with risk factors the percentage climbs and without risk factors it plummets. The news doesn’t like to tell you about the millions upon millions of people who feel sick, descend into their basements to ride out the symptoms, and emerge days later mostly unscathed. Still, there the dreaded “what if?” lingers in your mind when it’s you.

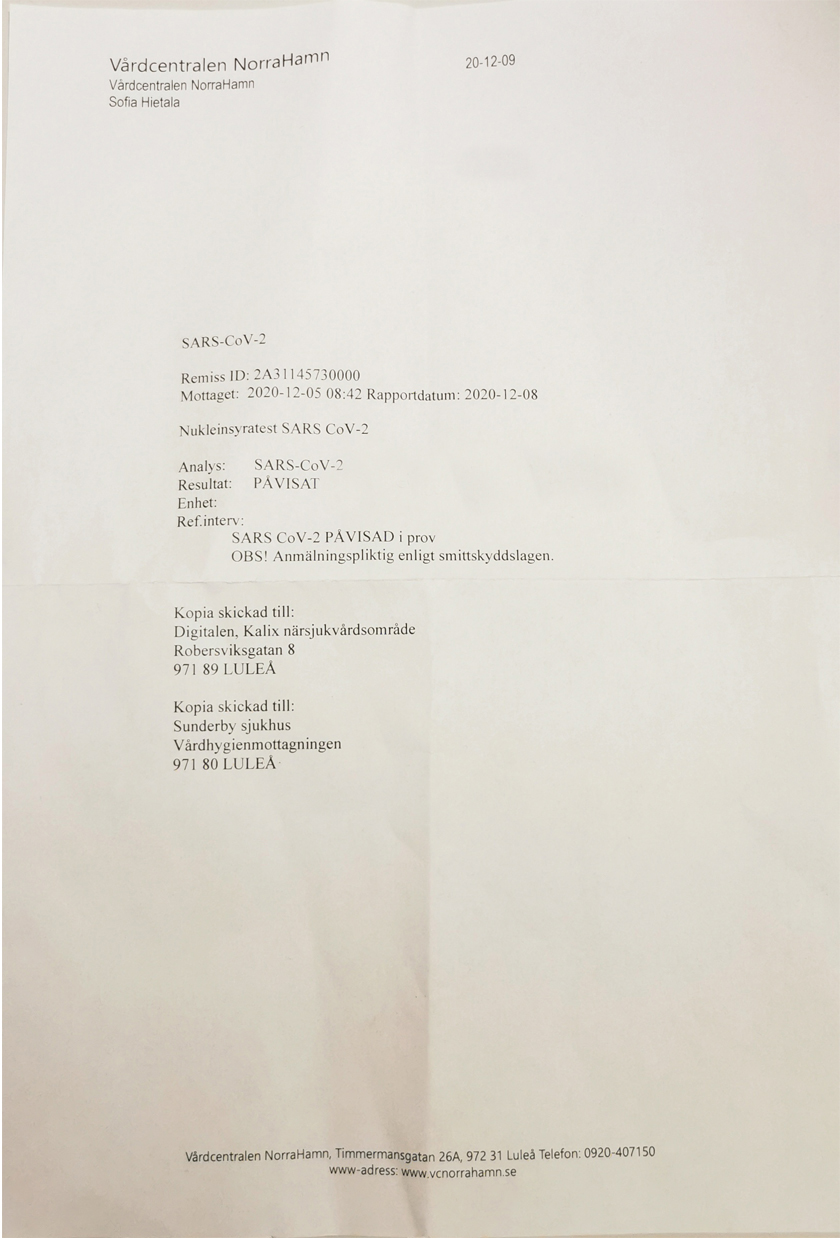

After what seemed a lifetime pondering over the details of my not yet spent lifetime, I was eventually able to sit up and construct a coherent thought or two. I could even sit at the desk and complete small projects. After 4 days of fever, delirium, and aches and pains, I got the sense that it had broken. I purchased a thermometer from a nearby pharmacy and took my temperature and, to my relief, it read a very normal 36.8 degrees. But was this just the calm before the storm that I should be dreading? What I had been told was that days 7 to 10 after the first symptom were the most critical.  I made daily excursions to the field clinic and five days after being tested the result was finally in. I had in my hands a positive test result and official documentation proving that I had contracted the coronavirus. The administrative assistant at the field clinic smiled when she handed me the paper and, behind my surgical mask, I smiled back with my eyes. There was something reassuring in getting the official result. For every story in the news about the terror and destruction that the virus had wrought, there was a fledgling news story about the virus being a hoax, that it was Bill Gates’ covert plan for total social control, or stories covering the lack of efficacy of tests that were providing scores of false positives and false negatives. Seeing the direct line from one positive result to my own gave me the sense that this democratic health system that operates outside of any one person’s control was effective not in spite of, but because of, its bureaucracy. I cannot recall ever having been so happy to have been a statistic. There was further reassurance in that my illness could not be directly attributable to Sweden’s oft-maligned stance toward aggressive lockdown measures nor my own lifestyle. Though both leaned heavily on one side of the pendulum between risky and cautious, it was bad luck and ending up at the wrong Airbnb on the wrong day that was the cause. Had I arrived in Umeå a week earlier and Brittmarie would not have yet caught the virus and had I arrived a week later she would have been ill and unable to host me.

I made daily excursions to the field clinic and five days after being tested the result was finally in. I had in my hands a positive test result and official documentation proving that I had contracted the coronavirus. The administrative assistant at the field clinic smiled when she handed me the paper and, behind my surgical mask, I smiled back with my eyes. There was something reassuring in getting the official result. For every story in the news about the terror and destruction that the virus had wrought, there was a fledgling news story about the virus being a hoax, that it was Bill Gates’ covert plan for total social control, or stories covering the lack of efficacy of tests that were providing scores of false positives and false negatives. Seeing the direct line from one positive result to my own gave me the sense that this democratic health system that operates outside of any one person’s control was effective not in spite of, but because of, its bureaucracy. I cannot recall ever having been so happy to have been a statistic. There was further reassurance in that my illness could not be directly attributable to Sweden’s oft-maligned stance toward aggressive lockdown measures nor my own lifestyle. Though both leaned heavily on one side of the pendulum between risky and cautious, it was bad luck and ending up at the wrong Airbnb on the wrong day that was the cause. Had I arrived in Umeå a week earlier and Brittmarie would not have yet caught the virus and had I arrived a week later she would have been ill and unable to host me.

With the positive test result came a checkup with a physician who listened to my lungs and measured my oxygen saturation levels and gave me the reassurance that the worst was behind me. The doctor was happy about how I had coped with the illness and the precautions I had taken not to infect others. Swedish protocols demanded that I could reintegrate into normal society only after 3 days without symptoms and at least 10 days from the first symptom. To be extra safe, I stayed in Luleå for two full weeks, and when I was symptom-free and felt well enough, I tracked down a hotel employee and asked to change to a room on one of the upper floors that at least had a window.

I had lost my sense of smell and I could only imagine what it must have seemed like to the poor person tasked with cleaning the room after I had gone. I had left stacks of pizza boxes in the corner and there was a bag filled with now rotting apple cores and clementine and banana peels. There was a set of bed linens with Rorschachesque mosaics of sweat lines stained into them heaped into a corner of the room and another set that I had been brewing in for over a week. During my illness, a maid came by on one of my previously scheduled check out days but I declined any form of turndown service in order to protect the staff. To finally be out of that dungeon was a relief, and though Luleå and the Amber Hotel will always be a special place because of what I lived through while I was there, I can’t imagine ever going back.

I had lost my sense of smell and I could only imagine what it must have seemed like to the poor person tasked with cleaning the room after I had gone. I had left stacks of pizza boxes in the corner and there was a bag filled with now rotting apple cores and clementine and banana peels. There was a set of bed linens with Rorschachesque mosaics of sweat lines stained into them heaped into a corner of the room and another set that I had been brewing in for over a week. During my illness, a maid came by on one of my previously scheduled check out days but I declined any form of turndown service in order to protect the staff. To finally be out of that dungeon was a relief, and though Luleå and the Amber Hotel will always be a special place because of what I lived through while I was there, I can’t imagine ever going back.

As I made my way up to Kalix now short on time to inquire about entry regulations into Finland, I couldn’t shake the thought that were it not for the state that the world was in, there would not have been much of a story to tell. I had lost the first half of December but by now my mind was sharp again and I could take a step back and look at my illness from a different angle. I realized I was not special, and thank goodness. The simple truth is I have had worse illnesses and the virus is not death and when you are clear of it you see the statistics of it far more accurately. I never want to suggest that there is nothing to fear, but the fear that the world has concocted surrounding the virus is far worse for the average person than the actual illness. The aches and pains of fever come and go and can be managed with medication, but the psychological turmoil of talking about dying and worrying about ending up in hospital stays with you the whole time.

I travelled out to Haparanda where there is one pedestrian crossing leading to a megamall on the Finnish side in the town of Tornio. People from the respective communities hop back and forth across the border to the mall sometimes just to get a milkshake. Local traffic was able to travel through, but there were no public transit options from one side of the border to the other. A makeshift fence was blocking the route to the mall and two officials in a van were controlling traffic. In my friendly and honest way, I explained who I was and what I was hoping to do. They looked at me as though I were a pig in midflight. I had to even go back further and explain that the reason I had come on that day was just to ask questions, not to actually cross, because the world was so weird. They asked me where I wanted to go and all I could say was to the north of Finland. They asked me how I would get there, but I had no idea. The winter solstice was just 2 days away and getting up to the north of Finland would surely take up those days. I asked if they would let me take 2 days to travel up there so that I could quarantine in the north. They laughed. They said they would only let in residents of Finland, or non-residents with family members in Finland who were residents. For all others, it was a hard no. I began to try to negotiate with them about places to quarantine and providing proof of a negative test result but it was starting to get complicated. I began to ask myself how important this all was to me.

Travelling north of the Arctic Circle for the solstice was the primary objective and entering Finland by any means necessary posed a threat to that. To their credit, Finland was a model by European standards of the effectiveness of strict lockdown measures, so trying to undermine the logic of their protocols was a losing battle and I was not willing to engage or try to charm my way across the line. I could, however, simply search for alternate routes along my path to nowhere in particular and Sweden does have well-established communities in Lapland. I turned around and went back to Kalix and on the 20th of December took the bus that rides the northern route through Töre up to the old mining outpost of Kiruna.

The next morning I laced up my boots, put on my coat and my mitts, and walked out into the woods at the edge of town following the snowmobile trails through the forest. It was a spectacularly clear day, and though the sun would never rise above the horizon, at midday it lit up the sky enough to turn the clouds pink and light the paths along the way. For a few hours, the sky on the southern edge of town sparkled purple and blue with a line along the southern horizon of bright orange that drifted from left to right. They say that no matter what hardships you endure along the way as you travel through the darkness the sun will come out tomorrow except that this was my day without a sunrise. It was the shortest day that I would likely ever experience in my entire life but it was not even the darkest day that I would face that December. That darkest day was spent in a hotel basement in Luleå worrying that I might not have the chance to see this day on this day, or hug my mom again, or tell this story because the palace of fear that we had built for this monarch of all illnesses, clad in invisible robes, was so grand that we have lauded upon it more power than it deserves. The darkest day is not the one without sunlight, it is the one spent afraid.

My story with the coronavirus has a happy ending, but not everybody’s does. Brittmarie was much older, suffered from diabetes and asthma, and by every measure was considered high risk. She was never far from my thoughts that whole month since I had left her. I had met my objective and now it was time to devise a new plan for myself. The first part of that plan meant travelling back south at least to Stockholm, but on my way, I made sure to stop in Umeå. I walked over to Brittmarie’s house and left a small ornament by her door. I tapped on the window and I was delighted to see her scamper over and she smiled when she saw me. I motioned a thumbs up and she gave me a thumbs up back and we could see that we were both now okay. I blew her a kiss through the window and I was on my way.