The Horse Thief of the Red Deer River Valley

His name to the Plains Cree translated as Walks Off the Trail though it was long and difficult to pronounce for the white settlers on the frontier who referred to him as Reindeer John. He was a proud Blackfoot who was well respected and walked among the various bands of his First Nation brothers throughout Rupert’s Land from Dene Tha’ of the Northern Territory to the Cree and Algonquin of the Canadas. He had the reputation of a tracker and a whisperer who monitored the migration of caribou and moose from the northlands through the plains bringing messages across to the tribes and connecting French fur traders with local scouts. Legends spoke that the Beaver, Crow and Blackfoot trails were all forged from the shadow that he cast as he walked. He was responsible for facilitating more marriages across the plains than anyone by transmitting news between the various villages. Using his knowledge of the terrain and the migration of every beast within it, he negotiated treaties by demarcating hunting lands and mediating between chiefs. Quiet in his disposition, he never married or had children and those that sought to injure his reputation derided him by suggesting he preferred the company of the wild animals to women. Despite his life of solitude, by 1880 he was the most knowledgeable and trusted man on the frontier.

In 1877, Sitting Bull and Crowfoot parlayed for many months with the former and his people in exile from their hunting lands and seeking protection from the troops of the Great White Father. At the same time, the leader of the Métis was in exile in the Montanas for raising troops against the MacDonald government. For decades in the American Union, white soldiers had trampled across the plains spinning lies and killing without honour. They were lesser men and even worse soldiers, but they were relentless and flowed into the prairie like a tidal wave. White faces had been marching across the plains in the north for many generations now, but it was not the people that Reindeer John feared, it was their way of life. “Their guns that tear flesh are no more effective at killing than any child with a bow,” he used to say. “But the ho that tears the soil will destroy our grandchildren before they are born”. He abhorred farming. “It is for lazy men,” he used to say. “Their cattle are fat and don’t have the sense to run, nor could they were they not so stupid. The white men feed them the wheat and the corn and they grow fat and so do the white men that eat them. There is no hunt in any of them.”

In 1870, the British Colombia was admitted into confederation with the promise of a rail line connecting it to the Canadas and uniting them into a single country from ocean to ocean. Word of the iron horse and the fleets of pig iron motoring its way throughout the country had already reached the plains and Reindeer John claimed to have seen the beast with his own eyes. On his trusted word, Assiniboine, Cree, Mohawk and Métis mobilized warriors to conduct raids along the line aimed at stifling construction of the railway that would one day cut through sacred grazing land for the herds of migrating buffalo. Reindeer John was the most knowledgeable and trusted man on the frontier, but in the halls of the newly formed parliament, he was the word that spread between chieftains that pitted semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers against sedentary farmers and the industry of a modernizing world. The trains could move faster than legs could run, but they were heavy and expensive. In the halls of Ottawa, Reindeer John and people like him were a threat to the unstoppable march of progress, for without the railroad there was no country.

Since the 1840s, white ranchers had been springing up homesteads on the plains using the rich grasslands around the Red Deer River for grazing cattle. The Red Deer River Valley was the traditional dividing line between Blackfoot, Cree, and Assiniboine peoples, but white immigrants knew nothing about it and did not seem to care by building their homes and ranches along either shore. Whites did not hunt and, for the most part, were tolerated. When an industry for buffalo hides sprang up decades later and siphoned the herd’s numbers to a trickle, the natives took notice. The Finnegan, Dorothy, Drumheller and Kirkpatrick houses formed their own alliance along the river to protect their livestock and their livelihoods. To them, Reindeer John’s status as the most knowledgeable and trusted man on the frontier was a problem. They knew his politics and knew his standing among the tribes and, though he said little, his reputation spoke with a ferocity that frightened every white man on the frontier. Farmers and ranchers of the Red Deer River were eager to see railcars arrive knowing that they would ship more cattle and hides – and more money – in every direction. With so much capital at stake, the rail line was constantly protected by the Canadian government and, with their homes located along the line, they would be similarly protected.

On a clear day on the prairie, one man standing can see straight from the rocky mountain to the rocks and trees of the shield 1500 kilometres away. But down in the valley, large rocks rise and fall and the river water feeds the grasses and trees that can grow tall. It is the one place out of sight and where things can disappear. Horses and cattle need to drink and happily wander from their pasture lands down to the river free from predators and patrolled by warriors. Ranchers defended their livestock by branding their cattle with hot iron and bribing impressionable warrior patrolmen with alcohol. Because, for the hormone-addled warriors, the ranchers’ blond-haired daughters did not require the same amount of bribing, for the most part, everyone was happy.

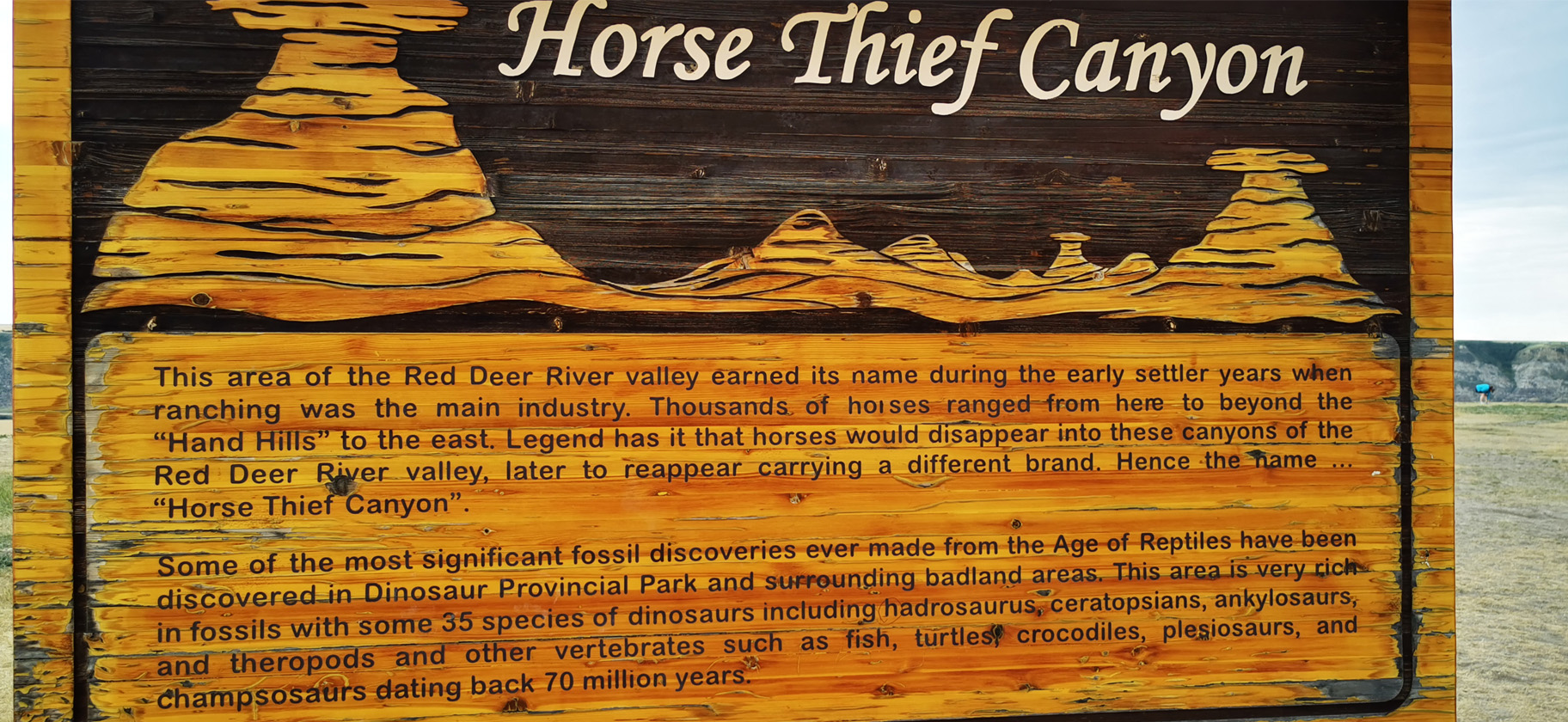

It was during Sitting Bull’s exile that horses and cattle in the valley began to disappear. When a dozen of his horses suddenly went missing, Kirkpatrick filed a formal complaint but, with no way to know where the horses had gone, no accusations were made. Dorothy and Drumheller suffered similar grievances and baselessly accused the boys of the nearby tribes. With no force behind their accusations and the train and the Mounties still hundreds of kilometres away, Crowfoot and his sub-chiefs warned the ranchers to mind their tongues and their manners. A year later, with the farmsteads near ruin, Mounties appeared with official letters and the force of the British army behind them. In what seemed a cruel joke, several horses later emerged from the valley with new branding on their hinds. “Letters do not speak the trust of our people,” a group of Red Deer River residents were told by one sub-chief. “Nor do we have a word for what you call ‘official’.”

On August 17, 1881, Reindeer John appeared before an ad-hoc district court of the Canadian confederation manacled and facing various criminal charges from the theft of no less than 300 units of horses and livestock to the rape and murder of 14-year-old Elisa Stanley. He was led into a make-shift barn with a single window where a dais was installed and a few chairs placed inside. It was a sweltering day in midsummer and the smell of piss and fermenting hay permeated the cabin by the river where a tiny contingent of men of letters would pass judgment on a man of the earth and sky. To give the court legitimacy in the eyes of a parliament that claimed lordship and jurisdiction of lands it had never seen, barristers were called in from Ottawa along with a missionary priest by the name of Albert Lacombe.

Prior to that day, Reindeer John had not been seen for many months and by the time Little Moose and Stinging Hornet reported to the villages that he had failed to meet them at a local tavern at their agreed upon date, the court had completed their trial and sentencing of Reindeer John. No material evidence connecting him with any of the crimes for which he was accused was ever brought forward. The only evidence submitted was a few short handwritten letters presented by the local ranchers. Though he spoke 12 languages, Reindeer John was illiterate and could not read the letters of accusation made against him. He collected no documents when he travelled only adding to his knotted lace of hemp that he wore around his waist as a record of his journeys and the tribal villages he visited along the way. To his people, it was accurate and an alibi as to his whereabouts at the time of the supposed crimes, but to the court official it was dismissed as a decorative trinket with no force of the law behind it.

Before he was sentenced, the judge offered Reindeer John the opportunity to speak some words in his own defence. Slowly and timidly, Reindeer John rose from his chair and with directness began to speak:

“This is about a railroad and your slow-moving beasts. You know that warriors will fight you as you build your railway and you aim to make an example of me. You Yengees bring ruin wherever you go. Your diseases don’t only kill men and women and children, they kill the ground as well. And because you can make a magic horse made of iron you think yourselves braver to the people who have been caretakers of this great Earth long before your ships crossed the oceans. I have walked through the great hills to the territories of the northwest – Vuntut, Gwitch’in and K’asho. I have crossed every plain and blade of grass and lake and river from here to the Algonquin, Mohawk and Wabanaki. I know this land and I know that your iron horse will destroy everything in it, starting with my people. It may take time – one hundred years even – we will all be gone but you will destroy the wildness of these lands and what makes them sacred. It is that same wildness that brings the caribou every year and without it, they will die. And then when all of the buffalo and the caribou are gone, so are we all. Still, you come with the paper that you have tamed from the wild trees and call them laws and the lies written upon them the final word, even against the one man whose word has been good on this frontier before the first buffalo was lost for no more than its hide. When the lies written by a corrupted heart can shape the world over the truth spoken by an honest man, what hope is there for humankind?”

That night, a mysterious fire rose high into the air overlooking Drumheller House. Inside its burning cinders was the beheaded and bullet-ridden body of Reindeer John and the last link that united every tribe from Hochelaga to the Northwest Territory. Rumours spread among the tribes of Reindeer John’s mysterious disappearance but there were few answers. Remembering the Battle of the Little Bighorn five years earlier, John A. MacDonald and the Canadian parliamentary war chiefs were not prepared to cede to any of the First Nations conditions but were wary about risking open war. Tribes united in their struggle posed a threat to parliament and the union of the provinces and the order went out to “shoot the messenger”.

“They will scatter like sheep without a shepherd,” quipped one official tasked with deciding the fate of Reindeer John.

“He speaks so highly of his herds,” said one decorated military official, “and where in nature predators cull the weakest of the herd, in battle it is imperative to identify, strike, and kill the leader. Once that is done, the whole herd is for the taking”.

Reindeer John was not a chief. He was a humble man and no great orator. He did not possess the skills to sway the minds of men nor did he have any interest in leading warriors into battle or counting coup. He preferred flowers and shrubs and above all the grasses. He led a simple and solitary life in which he never told a lie and for that the court which judged him was dismantled and his sentence of death carried out in secret lest he become a martyr for a cause. His execution was swift and ferocious and executed before the eyes of a catholic priest, Pêre Albert Lacombe. In the burning of the fire, all of the written complaints against Reindeer John went up in smoke. The law had only briefly appeared official and legitimate in the eyes of those at court, and procedure was promptly dismissed altogether when it dawned on those in attendance that the only means to the justice they were seeking was by the knife.

The name Reindeer John may not echo loudly in the annals of history, the stories of the meek and the tender-hearted rarely do, but with his murder, the history of North America was irrevocably altered onto the path that it has been heading for 140 years. Some among the First Nations were spurred into action. Poundmaker and Big Bear and other Cree braves resisted. Louis Riel returned to the Red River to take up the cause for his Métis and fought in the North-West Rebellion for which he would be hung as a seditionist and his reputation forever tarnished by accusations of insanity. In their victory, scholars of the Canadas put pen to paper on the history of the Indians of the Northwest highlighting their barbarism over their humanity and they have been cast as impediments to progress and economic development ever since. Before the year 1890 was finished, 250 of the southern plains Lakota Miniconjou – men, women, and children – were massacred by soldiers of the Union, and the last of the peoples of the Great Earth Spirit capable of resisting the tide of modernization were snuffed from existence.

The rail line blasted right through the mountain from east to west all the way to the sea and rushers pulled gold down from the mountain and sent it to the cities. Grasses turned to wheat and then to paper money and the deer and caribou retreated to the hills and forests and never returned to the plain. A highway eventually replaced the railway and petrol stations outnumbered the buffalo. For more than a century, smoke rose into the sky blocking out the sun and laying waste to the old-growth forests of the northwest. The tribes of the First Nations were fractured and pushed to the hinterlands and the hunt passed to them from their ancestors was stolen. They learned to read and write and farm the land and, in the ultimate triumph of the white man over the aboriginal land of the Canadas, they surrendered their honesty.

Generations of tradition and the spoken word were lost and mythologies disappeared. Laws evolved birthing a costume of conscience and reparations were made. Apologies were officially dispersed from a white government to the scattered fragments of once proud peoples who had been tamed over one hundred years by the rod and by disease. Still the smoke rises with the lights we keep lit day and night and that blight the stars of the night. Populations moulded in the frame of the white man continue to swell and push the people of the Earth to more distant and eroding corners of the land that are no longer wild and free. Still, they turn to those tucked into those dark corners and ask for more as the train tracks become a pipeline and communication towers. Pollution has seeped into every river that now needs to be treated with inert chemicals in order to be safe to drink. Soot and dust collect on every rock and stone and in the lungs of the fish that are now farmed in stagnant ponds and too lazy for the struggle to swim upstream. The soil yields no nutrition and there is no more food, only commodities.

Concrete and steel and the vast pastures of shit and runoff are the birthrights of domestication and the inheritance the white man leaves behind. Skyscrapers, stadia, and airports are the legacy that now exemplifies the unstoppable march of progress. Like the pyramids in Egypt, they epitomize what is achievable by mankind; they symbolize the subjugation of illiterate slaves by their masters with the force of the law behind them; they are tombs. Progress has wrangled itself free from those responsible for its creation and has taken on a life of its own with its own sense of self-preservation. Its shadow looms so large that even the white man and his principles are becoming displaced. Still, the law of the Land of Progress understands the imperative of silencing the spoken word of an honest man.

With the murder of Reindeer John, the Blackfoot had lost one of its most beloved sons. Since he was called Bear Ghost, Crowfoot could remember his brother who walked against the winds and away from the tribes in order to be with the bears and wolves in the forests and the wild moose, caribou and buffalo that walked the plains and grasses. He feared for his people and, as the tensions grew between the tribes and European settlers, for four years he looked to the horizon in search of his friend who never returned home. During those four years since his disappearance, reports exchanged between villages stalled and no longer came with the authority of Reindeer John. The truth eroded and no one could be trusted leaving every band, though united in their cause, to fight its battles alone.

On a stormy afternoon in the late winter of 1885, the missionary priest Albert Lacombe, sent by the parliament of the crown was granted an audience with the Blackfoot chief. Upon the conclusion of their meeting, it was decided that the Blackfoot would play no part in the North-west rebellion. After that day, Crowfoot, born of the Kainai, adopted son of the Siksika and chief of the Blackfoot Confederacy, never again looked to the horizon hoping for the return of Reindeer John. The heartbroken chief retreated from his authority and wept each day until the fighting stopped with the force of his leadership now forfeit. Forever remembered in white histories as a voice of reason and peace, it was whispered among those closest to him that, during their parlay, the priest had reported to Crowfoot, in all of its gory detail, the fate of Reindeer John on that sweltering day in the summer of 1881. Lacombe’s words as a witness reminded Crowfoot of what happens to those who oppose the crown. Lies though they might have been, and with no official word to support the priest’s claims, they nonetheless had the intended effect on Crowfoot’s spirit. Before leaving Crowfoot’s company, Albert Lacombe is said to have counselled him not to weep for all of it – the colonization of the Americas, the march of progress, and the murder of Reindeer John – was the will of God.

There is no monument to Reindeer John and no stone to mark his grave – those are the vain relics of civilization. Until his death, his spirit embraced the wildness of the world that he helped to shape as a committed steward of the Earth and all of the creatures in it. Today, his name no longer has any standing in the lands he once walked as those that trusted his word have died or been displaced. All that is left are the faint whispers of the Braves who continue to stand against injustice and seek to temper the unrelenting and unforgiving march of progress. For the rest of us, there exist tall tales about a horse thief in the Red River Valley as part of the Drumheller mythology whose renown now hinges on the discovery of dinosaur bones. The memory of those that sought to preserve these unspoiled lands has been erased – their struggle is just a little too tragic. History prefers not to tell the stories of the good men and women that it has sacrificed to obscurity in the name of modernity. It is the printed and mass-produced version of a tall tale describing the unstoppable march of progress and the evolution of humankind, but it is a history built on lies and the murder of honest men. When the lies written by a corrupted heart can shape the world over the truth spoken by a single honest man there is no hope for humankind.