Acibadem Sistina and the Health Certificate

It was sweaty and drab in the basement of the Acibadem Sistina Hospital, my arm bandaged and still stinging from the needle, as I slunk into the chair in the waiting hall, working on hour number 3 of the wait, and wondering what I was even doing there. I was trying to put all of my ducks in a row and just wanted to be ready to leave. I wanted to have a plan in place and it only felt right with all of my documents sorted out. When I had spoken with the physician, he seemed perplexed but said that he would run some tests and then at least he would have something to put into an official-looking report. I was happy to submit to whatever could get me the certificate I needed.

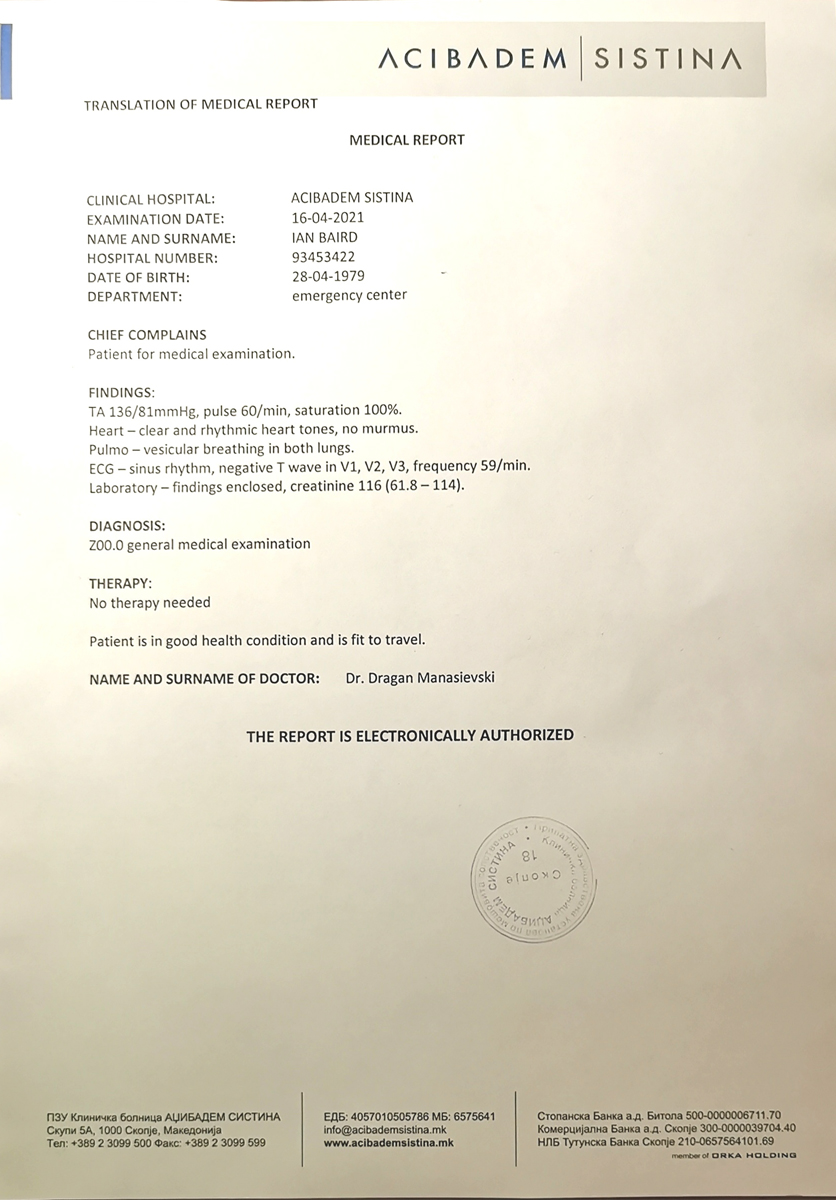

Soon after arriving in Macedonia, I reached out to Mathieu about travelling to Indonesia – something we had been working on for four months – and the Indonesians had just opened their doors to travellers with business visas. He put me in touch with a lawyer who put together a list of all of the documents I would need in order to be granted a visa. The list included: a copy of my passport; proof that I had sufficient funds in my bank account; my signature on a waiver explaining that should I become ill with the coronavirus, it was my responsibility to pay for any hospital care; and a health certificate signed by a physician asserting that, at the time of submitting my application, I was in robust enough health to make the journey.

By the time I was finally called into the office I had been waiting long enough to become impatient. At the doctor’s orders, I propped myself on the inspection table as a nurse entered and wrapped a cuff around my arm to take my blood pressure. The cuff squeezed tightly around my arm as machines beeped and whizzed. The doctor, with his stethoscope on my chest, asked me to take a deep breath. A series of masked nurses entered the room and I was asked to remove my shirt and lie down as they affixed a series of bulbous clasps to my chest. The doctor’s office was now filled with several nurses coming and going prodding at me with instruments. None of us could understand each other but I sensed that they were trying to tell me to lie perfectly still. The cuff tightened around my arm again. A machine spat out a trail of paper that the nurses inspected and passed to the doctor as they removed the clasps from my chest that had left a series of swollen welts. The doctor muttered something in Macedonian and the nurses came charging back and telling me to lie down. They fastened all of the clasps again and told me to be calm and lie still which was tricky because everything in the office at the moment was so frantic. The machine spat out another trail of paper which the nurses passed to the doctor.

“Do you smoke?” the doctor cried out from across the room as the nurses began to undo all of the clasps that left another series of welts.

“No,” I replied.

“Do you ever get chest pains?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “I don’t even know what that would feel like.”

The nurses left the room and I put my shirt back on and sat in the chair across from the doctor as he went through the results of my tests. He pointed to a few items and said that I should drink more juice. I must have been dehydrated which was understandable since I had walked the five kilometres out of town to the hospital through the heat of the day. The doctor nodded his head back and forth and pursed his lips. “More or less, everything is normal. Blood pressure is a little high, but maybe you are a little bit nervous.”

He inspected the papers that the machine had spat out – ECG results – and, with a pen, indicated spots on the reader that indicated an abnormality. “This is an inverted T-wave,” he said. “You don’t smoke and you don’t have pain in your chest?”

“What would a pain in my chest even feel like?” I asked.

“You would feel like you were unable to breathe. It would last for several minutes.”

“I have been an athlete my whole life,” I replied. “I play football and run 90 minutes. I hike 10 to 20 kilometres several times a month. I have never had a problem like that.”

He shrugged and pointed to the ECG and said: “This is objective.”

At that moment, my heart broke.

“It’s okay if you feel okay, but this is objective. Whenever you return to your country you need to see a cardiologist.”

He signed and stamped the papers which the liaison officer then translated. I paid my bill and had all of the documents I would need for my visa to Indonesia. For a cool hundred dollars, I had bought a brand new problem that I was going to carry with me every step of the way.

I left Acibadem Sistina Hospital with a thousand questions that would have no answers for months. Would that I could even understand the answers in this strange place. North Macedonia was an afterthought. I had hedged my bets that I could escape Switzerland and avoid paying the 200 Swiss francs for a PCR test and it had worked. PCR tests from Biotek Laboratories in downtown Skopje were cheap and included a fit-for-travel certificate. Flights to Istanbul were even cheaper from Skopje than they were from Tirana and they were letting in visitors without imposing any kind of quarantine so I figured why not stop. With all of the uncertainty this pandemic world created, it seemed like I was making every right choice. But, as I walked along the Vardar back toward the city and to my hotel, I would have happily paid many times that price to go back and never have to have heard those words that now echoed in my brain: “This is objective.”

You tell yourself that you feel fine because you feel fine, but you question yourself because a machine and man in a lab coat tells you that you are not fine. This is objective. It becomes hard to know who or what to trust. How do you follow your heart when your heart has just failed you. After all, what was on that ECG printout was objective. It was cold. It was scientific. It was trustworthy. In a chaotic world, it was grounding. It was truth. It was objective.

My heart was pulsating at 60 beats per minute – eighty-six thousand four hundred beats every day, give or take, without me even having to think about it. Now, each one was all I could think about. I could tell myself that I felt fine and that I had always felt fine. That was how I felt, but the machines were objective.

I returned to my hotel and sent off all of the documents to the lawyer. I retreated into my work and tried to concentrate on other things and keep my focus away from the beating in my chest but always wondering if that heart was getting the blood it needed. Ascending the steps from my room to the lobby I felt out of breath. Was it because I lacked exercise? Could it be because I was forced to wear a mask that impeded my breathing? Could my failing heart no longer be ignored?

I returned to my hotel and sent off all of the documents to the lawyer. I retreated into my work and tried to concentrate on other things and keep my focus away from the beating in my chest but always wondering if that heart was getting the blood it needed. Ascending the steps from my room to the lobby I felt out of breath. Was it because I lacked exercise? Could it be because I was forced to wear a mask that impeded my breathing? Could my failing heart no longer be ignored?

I had aged a decade in the time it takes to whisper: “this is objective.” I felt old. I did not know my body and my heart no longer felt a part of a whole me. My heart was encased in my body, but that section of me no longer felt mine. My heart had abandoned ship; It had quit the team; It had been replaced by the tick-tocking repetition of the words, “This is objective”. I became easily distracted and found myself researching my condition and its relationship to cardiomyopathy. Was this going to be my life now? Pills, tests, scans, checkups, and pre-existing conditions? My heart sank when I thought about ticking various boxes when requesting insurance quotes and how it might affect my premiums. I thought about going on dates. What woman would want to hitch her wagon to a star with a heart condition? I could tell her that I felt fine, but the scan was objective.

I was transported back fifteen years into my past to Chichicastenango and the steps of the Iglesia de Santo Tomás where there sat a spectre clad in robes of torn black rags, her long black hair blowing in the wind. The witch and her devil-eye reflected my fate back at me. There, I was grey and calm and happy, but she was from the realm of the spirits and the printout from the hospital was objective.

I kept replaying those moments in the doctor’s office in my head. It was frenzied and happening in a language that I did not understand. I tried to slow it all down and scrutinize every detail. Mistakes happen all of the time. I could see each electrode hovering over me like tiny octopi with teeth. The machine seemed old and inaccurate and, in its way, subjective.

I went for a stroll through the forest of Gazi Baba Park to clear my head. Before Skopje and my visit to Sistina, I had never given my long-term health a moment’s thought. I had been an athlete for my entire life and was blessed with a stable and predictable metabolism. My weight rarely fluctuated and, with minimal exercise and maintenance, I was able to sustain my physique. I have always just assumed I was destined to live a long and healthy life and would one day in the far off future die young at a ripe old age. I was one sleep away from flying to Istanbul and my journey through the Eastern Wall was about to become a reality. I had all of the documents; It was all above board and legal; This was what all of the work was for but all I could think about was my heart. It continued to beat inside of me and I continued to travel, work, rest, repeat. How many more sleeps? How long would it be before I would have real answers? I began to think about returning to Canada if for no other reason but to put this new problem behind me. But that was before the pandemic. Going back was no longer so simple. Walls were up. The only thing to do was to keep moving forward. As long as I felt fine, I was fine and no ECG printout was going change that. The plan was still the plan. My rucksack was now a little heavier than when I had arrived in Skopje. I was dragging a weight with me everywhere I went in the words: “This is objective.”