A Well-Reasoned Argument for the Impotence of Well-Reasoned Arguments

“You’re waiting for a train. A train that will take you far away. You know where you hope this train will take you, but you can’t know for sure. But it doesn’t matter, because we’ll be together.”

What if none of this is real?

Theories continue to be posited that this tiny universe in which we live is nothing more than a simulation designed by a very sophisticated AI. Even if it is not, it is difficult to nail down just whose reality this actually is – yours or mine. Perhaps it belongs to someone else and we are just extras in their comedy. This whole universe whose frontiers remain theoretical and too vast for us to stretch has no certain origin. We have plausible and well-designed theories supported by predictive math until a divine hand, or a superior intelligence undoes the whole thing. Theoretical physicists are optimistic that our collective culture and our brightest minds will one day get us to a simplified and absolute theory of everything but, for now, our ways of explaining what is, and why, are built on good ideas and good math and nothing more. You can walk down a beach and grab a small stone and drop it to the sand and it will fall and land every time – until it doesn’t. The probability of the stone not falling to the Earth when dropped is so low that the maths on it is impossible for a layman such as me to calculate. But the likelihood of a dropped stone not falling to the Earth is still more likely than you or I – and yet here we are. It is also scores of trillions of times more likely than anyone ever-changing their mind because of a well-reasoned argument.

In Zurich, on the northern shore of the Limmat, there is a walkway where, while strolling through the rain, I came upon a shelf for used books. On it, I found an English copy of 1984 and, as I am always in need of something to read, I picked it up. Nineteen-Eighty-Four was required reading material in high school so I had turned every page at least once and was familiar with the story. Moreover, the material has become so well known in pop culture that even people who have never read the book understand that it is to dystopia what the Torah is to religion. Even a first-born son understands their relationship with Big Brother.

As a lesson, 1984 is brought into the consciousness of teens as a warning based on what Orwell observed at the conclusion of the Second World War. It was written as a possible future if humankind played out the scenario in which it found itself back in 1948. In January of 1984, Apple produced a television commercial hyping the release of its flagship product, the MacIntosh, with the line: “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.” Nineteen-eighty-four is the story of a disgruntled government employee named Winston Smith who enters into a relationship with a woman named Julia. The first part is dedicated to building the world and the bureaucracy in which Winston lives. The second part deals mostly with Winston’s relationship with Julia. In the third, and final part, Winston is tortured by a man named O’Brien, he is told the truth about The Party and about Big Brother. The book is grim. There is no riding off into the sunset for Winston and Julia. In the end, they even confess and betray each other. There is no escape from the dystopia in which they find themselves.

Ancillary to the plot is a book within the book called, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism by Emmanuel Goldstein. This is the part of 1984 that does not stick when you are a high school student, especially in the 90s when I was growing up and it was assumed that we had avoided Orwell’s gruesome vision of the future. Reading it today was bone-chilling. Not only does it read as though we failed to avoid the author’s ominous warning but it was, instead, the playbook that we have followed over the last thirty years to ensure all of Orwell’s worst fears were realized. In possibly the saddest example of irony, humanity was given a master treatise on what not to do to build a better society and, perhaps completely out of ideas, pieced together the frightening society that Goldstein’s essay outlines.

New optimists will say that life is not nearly so bleak today as the world that Orwell imagined. “Look at the statistics,” they will say and point to the quality of life of a poor person today to that of someone of the peasant class from 300 years ago and suggest that we have made progress – as if that were the point. By 2021, one of the most pervasive topics in the news that captivates social scientists is the growing wealth inequality not only in Western states but around the world. And then you read Orwell (as Goldstein) as he outlines society as always intentionally hierarchical and comprised of the high, the middle, and the low, and it dawns on you that that is the point.

One of the first times I ever had my scholarly preconceptions completely smashed was taking Professor Trigger’s Egyptology class at the University of McGill in 2001. Going into any class about Ancient Egypt, it is easy to get doughy-eyed about the prospect of learning about Cleopatra, sphinxes and pyramids. But Professor Trigger’s class was nothing like that. It was about lists of unpronounceable names of dynastic lineages, the composition of silt from Nile floods, and interpreting fragments of pottery to determine their dates of origin. Back then, there were a few gaps between dynasties which Professor Trigger referred to as Dark Ages. Until then, the only Dark Age that I knew about was in Medieval Europe where intellectual and cultural progress, so I was taught, halted until the Renaissance. One of the key features of these Egyptian dark ages, he pointed out, was that there was a distinct absence of written court materials from these periods. He was not shy about signalling that the only real difference was that there was no pharaoh and no court. While waving his finger at his students, Professor Trigger made me realize that these dark ages were characterized by a levelling of the playing field, likely brought on by a disaster or climatic pressure, where the difference in the standard and quality of life between the peasant and the king was not so distinct. You do not look at monumental architecture or royal palaces the same after that – they are all monuments to inequality. In fact, Golden Ages tend to represent a widening of the divide between kings and their subjects where those in charge are able to mobilize millions in pursuit of their own interests.

Orwell (as Goldstein) writes:

“But it was also clear that an all-round increase in wealth threatened the destruction — indeed, in some sense was the destruction — of a hierarchical society. In a world in which everyone worked short hours, had enough to eat, lived in a house with a bathroom and a refrigerator, and possessed a motor-car or even an aeroplane, the most obvious and perhaps the most important form of inequality would already have disappeared. If it once became general, wealth would confer no distinction. It was possible, no doubt, to imagine a society in which wealth, in the sense of personal possessions and luxuries, should be evenly distributed, while power remained in the hands of a small privileged caste. But in practice such a society could not long remain stable. For if leisure and security were enjoyed by all alike, the great mass of human beings who are normally stupefied by poverty would become literate and would learn to think for themselves; and when once they had done this, they would sooner or later realize that the privileged minority had no function, and they would sweep it away. In the long run, a hierarchical society was only possible on a basis of poverty and ignorance.”

But Orwell’s 1984 was just fiction. It was nothing more than a grim tale of a world of unfettered propaganda and constant surveillance. By the time the real 1984 came around, the fascists had been ousted and even the threat of communism was winding to a close as the tensions of the Cold War were beginning to ease. The wounds of a once fractured Europe were healing, humans were venturing into the frontiers of space with regularity, and the world was becoming increasingly cooperative as the global consciousness was being piqued by fundraising initiatives like Live Aid – a benefit concert that was broadcast around the world. There was optimism that we had defeated the spectre of Big Brother.

Of course, it wasn’t perfect. Hundreds of millions of people still lived without basic necessities and bombs were still being dropped in distant corners of the world, disasters and diseases still crept up from time to time, but we responded; we were working on it. The world was becoming increasingly connected. Access to information was becoming cheaper and more readily available. And then came the internet which promised to make literate those who are normally stupefied by poverty. With digital technology and free access to information, everyone would finally be able to think for themselves.

Technologies were being designed to free up our time to leave us to more worthy pursuits and for many that dream became a reality. Tech giants stepped into the present and delivered devices and software that was once the dream of science fiction. But like load-bearing walls holding up a roof, jobs collapsed and wages at the bottom stagnated while the fortunes of the wealthy grew, and now the castle is teetering perilously on the tip of a toothpick because it is still the almighty dollar that puts food on the table and a roof over one’s head.

I heard once that, “The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” In seventy-five years we became so convinced that Orwell’s vision would not happen that it did not happen. Even today, we refuse to acknowledge that it did, in fact, happen.

I have lived through forty years of innovation. I can have just about anything I want rush-delivered right to my door within 24 hours. I can watch my favourite sports in marvellous 4k HD video so clear and vibrant that I can see the sweat on the athletes’ faces. We can launch a rocket into space, land it on the moon and then launch from the moon and land it back on Earth. But I still can’t get my bank to change my transit number to my nearest branch from the branch where I set up my account, I have yet to find an elevator with a ‘cancel’ button for any time I push the wrong floor, and we cannot seem to figure out a more fair and equitable distribution of wealth and the Earth’s resources, or a more streamlined, efficient, and cooperative system of government than the ones we have. It should not have to take the sight of a lineup of people waiting for a bag of free rice delivered by an NGO to make you realize that if one man needs to have a yacht to accompany his yacht, that something is seriously wrong.

I cannot help but think that this must be the world we want – a world of startling innovation blended with a frustrating apathy toward seemingly simple fixes. We tend to gawk at staggering, paradigm disrupting, discoveries and fall asleep at the wheel when it comes to simple quality of life adjustments that could improve the lives of everyone. To hear theoretical physicists make predictions about the state of scientific inquiry and where they anticipate humans will be as a species technologically in the next 100 years seems to have us on a path of inevitability. Social scientists speak about the world’s human population peaking in 2050 at around 10 billion and there is a fait accompli in the rhetoric they use. What is it about humanity that we cannot shake from the course that we are on? It seems incredible that we can launch humans into space and send out satellites to explore distant galaxies. But just because it seems impossible but isn’t does not make it a universal good. Our existence is hurtling forward, being propelled by the positive and negative consequences of our needs and desires and rarely do we take time to stop and think about what we are doing as if because we can means that we should.

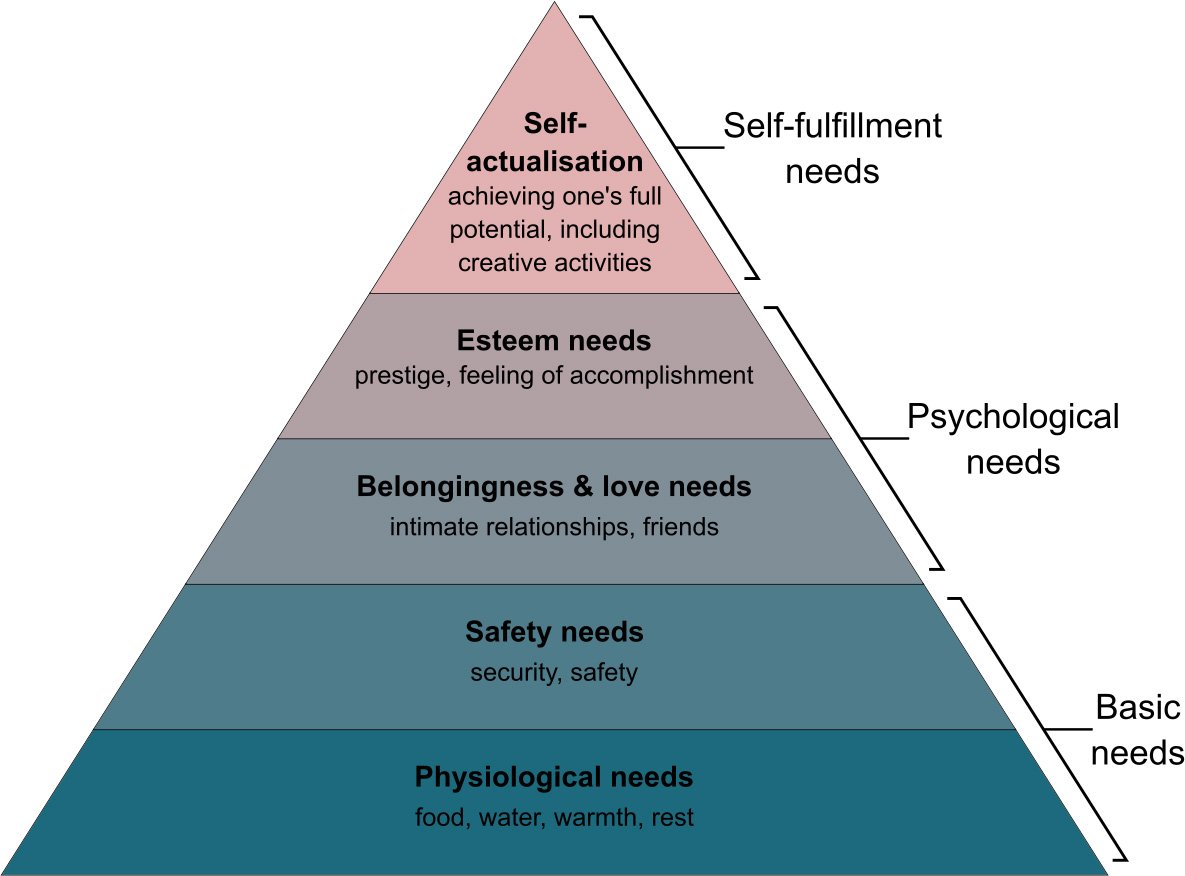

Looking at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, all of the needs at the base of the pyramid are easily achievable yet still out of reach for so many. Between the layers of the physiological and the psychological is an imaginary line which is the monetary resource minimum. It is the value in dollars that is required to meet a person’s physiological and safety needs, but no other needs are achievable below a certain monetary threshold. One cannot begin to conceive of esteem and self-actualization if one is constantly fighting to meet the needs at the base of the pyramid. Because society is hierarchical, the goalposts determining what are basic needs shifts over time. Those occupying the low – the proles – can never achieve self-actualization or any feeling of accomplishment because they are always striving to reach the inflating monetary threshold that borders on safety. New optimists believe that providing running water and electricity means that the low are rising out of poverty – they are not. What is meant by “poor” is simply changing and esteem and self-actualization remain out of reach.

Looking at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, all of the needs at the base of the pyramid are easily achievable yet still out of reach for so many. Between the layers of the physiological and the psychological is an imaginary line which is the monetary resource minimum. It is the value in dollars that is required to meet a person’s physiological and safety needs, but no other needs are achievable below a certain monetary threshold. One cannot begin to conceive of esteem and self-actualization if one is constantly fighting to meet the needs at the base of the pyramid. Because society is hierarchical, the goalposts determining what are basic needs shifts over time. Those occupying the low – the proles – can never achieve self-actualization or any feeling of accomplishment because they are always striving to reach the inflating monetary threshold that borders on safety. New optimists believe that providing running water and electricity means that the low are rising out of poverty – they are not. What is meant by “poor” is simply changing and esteem and self-actualization remain out of reach.

The connection between esteem and self-actualization to power and modern monetary wealth cannot be overstated. We are reminded that money cannot buy happiness to say nothing of the fact that an adequate amount of it can buy esteem and self-actualization and more of it can even buy power and influence. If a miser buries it like treasure, or a fool squanders it, that speaks nothing of what wealth can do in different hands. In short, the more you have, the more you control. Lord Acton once wrote that: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” He missed the mark by failing to acknowledge that it is only the corrupt that seek power. Be wary of the people in your life with everything and who, for some reason, covet more.

At the heart of corruption is the inheritable nature of control in the form of wealth and power. Lineages of failed Pharaohs and Caesars over centuries, to cruel monarchs clinging to their station at any cost, and Kaisers with colonial aspirations have shaped the world we live in by pitting mild-mannered prole against mild-mannered prole of a different stripe. There was once a tale of a noble savage that lived wild and free in a lush garden, master and servant of their domain, living in peace and harmony with all around them. And with wealth and power came the scholarly articles to explain that it was never so. They leave out how those who wished to live in peace were slaughtered by those who wanted more for themselves. Is it an oversight, or is it intentional?

When the pandemic first began sweeping across the globe and we were forced to shut ourselves in our homes there was a hope that we would rise from this challenge and build a better world. There were many who looked at the situation as an opportunity to stop and think about the kind of civilization we were forming. This was our chance to evaluate where we were headed and this was our chance to right the ship. But as time lurches forward, still it seems we draw closer to the iceberg in the distance with no impetus to adjust our heading. Instead of bringing us together, it seems the pandemic has widened the divide and has left us all traumatized. Instead of diverting efforts to other pressing issues, Covid-19 has become an all-consuming issue that is our first thought in the morning and last thought before we go to sleep at night. Since March of 2020, I can scarcely recall a conversation I have had where the subject of the coronavirus did not come up. Instead of an annoyance that operated in the background, the virus seeped its way into every corner of our daily lives. It affected our decisions, worked its way into public policy, and changed the way we looked at others. I cannot help but think that this must have been the outcome we wanted because were it not we would have done things drastically different.

It seems crazy to suggest that what happened to the world in 2020 was what anyone wanted. On an individual level, as we stared out from our homes like frightened gophers, it is silly to suggest that covid-19 added to the vision of a utopian future. But humanity is a collective and, since March 2020, it seems as though there has been an inevitability to the outcome of this plague as though only one story could be told. There are reassurances in the media that when we finally tame this virus that life will return to normal and we should expect an economic resurgence similar to the roaring 1920s. For those in the media, the government, and anyone in the high, an economic resurgence indicates that the problem has been solved – it keeps the stones moving, builds the monumental architecture, props up the monarchy, and lights the halls walked by elected kings.

The pandemic is water and, over the last year, it has nourished the soil upon which we have sown distrust and false belief. It was while working on an interview with a lawyer from the Innocence Project that I first became acquainted with the idea of false confessions. It became a small obsession as I tracked down documentary series and short segments in popular literature on the subject. In incidences where an individual is believed to have given a false confession, there is a tendency on the part of those examining the situation to ask the question, “how could someone confess to something (a crime) that they did not commit?” We think to ourselves: were I in the same situation I would never be broken down and confess to something that I did not do. What you learn from all of these studies and documentaries is that the fatal flaw in all of these subjects who confessed to crimes that they did not commit was that they were human beings. We can all be broken.

We believe a thousand lies a day and popular culture has taught us that “the broad masses of a nation are more easily corrupted in the deeper strata of their emotional nature than consciously or voluntarily; and thus in the primitive simplicity of their minds they more readily fall victim to the big lie than the small lie”. Our frontal cortex allows us to doubt and question and contemplate our reality unlike any other species on the planet but, make no mistake, we are all products of conditioning. Whatever our motivation, the only thing that will decondition us is striking to our emotional core, the promise of sex, or pressure – facts and evidence have had their chance to win the day and failed.

Our receptivity to any idea determines how deeply it will penetrate and take hold of our perception and conform to our reality. There is a consistency to any point of view no matter how many fallacies and inconsistencies, or how much cognitive dissonance, may be required to keep it standing. This is why evidence does not suffice, why a well-reasoned argument is a masturbatory exercise, and why alternative facts rise to meet and challenge actual facts. Every piece of news gets split down the middle and retold a thousand times, not to inform, but to conform to the established framework of the reality of its intended audience. Every thread of information is gathered by the brain and mutated to fit comfortably into our pre-existing framework of thought. The concept of confirmation bias has risen to prominence in the modern lexicon and Orwell had seen evidence of the minds of modern people falling into this trap long before there was a snappy definition handed down from pop psychology when he wrote: “The best books, he (Winston Smith) perceived, are those that tell you what you know already.” There is no news – only propaganda.

Lies seep into every corner of our thought but they are necessary to keep the structure intact because we have believed so many lies for so long that the fabric of our society is built upon them. To now unravel them in the pursuit of the real and fundamental change that we require to build a fairer society would collapse our reality like a house of cards and that is a bridge too far for us as a species to walk. Would only that the human mind was incapable of lying for personal gain, would that there were nothing to gain through lying, and would that there were nothing to gain but the truth for its own sake. Lies are the social contagion that keeps the hierarchical structure in place and props up our increasingly irrelevant institutions who, fading from existence and held together by a deranged imaginary concensus, double down on reminding the world of their importance by infiltrating every aspect of our lives from taxes and trade wars to sowing cultural discord and ignoring issues of immediate and global importance.

When I was young, during our yearly summers camping in Cape Cod we would always have a bottle of Ocean Spray cranberry juice on the picnic table. It was only available in Massachusetts; It was tart and refreshing; It was served in a glass bottle and, on the label, there was only one ingredient: cranberries. Competing with Kool-Aid at the time, it was uncommon for a 7-year old to enjoy the sharp acidic taste of fresh-pressed cranberries but I loved it and was as happy as anyone to see it arrive on Canadian grocery store shelves in my teens. Thanks to NAFTA I could get Ocean Spray cranberry juice at my local grocer any day of the year instead of only enjoying it for a few weeks of summer in the US. But it wasn’t the same. It was served in plastic and was now a mish-mash of ingredients aimed at approximating the experience of drinking cranberry juice while reducing costs and increasing shelf life in an effort for the constantly expanding Ocean Spray cooperative to increase revenue and profits. It is undrinkable.

Cranberry juice does not stand alone in its deception. Some of the most influential brands in the world are food and beverage conglomerates whose products provide us with little to no nutrition. Instead of being informed about the harmful effects of these food-adjacent products we are bombarded by warm and fuzzy advertising for these addictive substances only to pay the social cost later on like when a pandemic that disproportionately affects the overweight and obese passes through town. All of this is done in the name of profit. This must be the world that we want otherwise, in any sensible freethinking society there would be some accountability.

We have lived for decades, perhaps centuries, in this approximation of reality that keeps people in their place whether it be high, middle, or low. This is the playbook of the Oligarchical Collective as they drop one grain of sand at a time into the river until they have built a dam and there is no water for those downriver to drink. And when those who live downriver cry out that they are thirsty, they who own the dam sell the once-free water back to them while criticizing them for not having the forethought to invest in sand. Everything you work to own was first stolen from you. To see it, it just needs to fit within the framework of your reality.

The pandemic brought every eerie, twisted, and demented facet of human-to-human interaction to the fore. Instead of fostering solidarity, it widened the divide between the high, the middle and the low. The responses of states around the world attempting to curb the spread and stem the burden upon their healthcare systems repeatedly seemed random and arbitrary. In the media, it was often reported as downright contradictory. Experts examined the evidence and made statements to the public that were later proven to be false. They backpedalled on medical and public health advice because it was better than getting up to the microphone and admitting that they did not know, did not have a reasonable answer for why they were advising public officials on new policy, or flat out admitting that they were wrong and apologizing. What people heard and what they believed depended on what camp they were in. They were either unreasonably outraged in surrendering a modicum of freedom or disappointed that their cage was not more confining. They came to the table to get their daily dose of confirmation bias from whichever media outlet they watched and aligned with rage or delight depending on who held political office in the United States. Like Ocean Spray cranberry juice, news became an approximation of our reality that was undrinkable. Strange and mysterious theories labelled as conspiracy circulated through fringe and mainstream media outlets leading folks on one side to say: “see!” and folks on the other to say: “for fuck’s sake!” The only thing that is truly shocking is that the folks saying “see!” were repeatedly surprised to have their worst fears confirmed in their own minds and those saying “for fuck’s sake!” were repeatedly surprised by the same theories brimming to the surface. When you believe in lies, how can you be surprised by anyone’s belief in a lie? At this point, why does the human quest for conspiracy surprise us?

Alan Moore said: “Conspiracy theorists believe in a conspiracy because that is more comforting. The truth of the world is that it is actually chaotic. The truth is that it is not The Illuminati, or The Jewish Banking Conspiracy, or the Gray Alien Theory. The truth is far more frightening – Nobody is in control. The world is rudderless.”

The real conspiracy, in fact, is that we do not have the freedom to believe that 2+2=5. Orwell made a point of saying that: “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.” There are certain things we need to be able to agree upon for the world to properly function. Just because no one is in control does not mean the world is completely rudderless as Moore says. Two plus two makes four and if you drop a stone it will fall to the ground – we have launched rockets to the moon on such principles. What we have not done is built a society where we have the permission to be wrong and believe that two and two make five because being wrong is more threatening to our reality than it is to our existence. When there is nothing to gain, then being wrong about anything is completely benign.

Other popular catchphrases that have risen to prominence over the course of the pandemic are things like: “Science does not care what you believe” and “You are entitled to your own opinions, but you are not entitled to your own facts.” Yes, it does, and yes, you are. Prove me wrong – I have nothing to gain. We will still be able to launch rockets to the moon, develop life-saving vaccines, and prove, that, despite our best intentions, in a functioning democracy competency is not a prerequisite to wield power. We delude ourselves into thinking that our politicians are creating policy based on science but they are not. At best, policy is based on sound scientific theory. Science is a method and it will continue to progress one funeral at a time because science admits to the failure that we cannot – unlike our democratic institutions, gasping for air and struggling to stay relevant, science has nothing to gain.

Deep inside of us, the impulse to evangelize our point of view persists. Each one of us sits at the ready like Manchurian Candidates awaiting the trigger word to carry out our mission whenever someone challenges our version of the truth. It is because according to Orwell: “It is not enough to obey Big Brother: you must love him.” It is one thing simply to live within the well-built framework of lies in which we find ourselves, it is something else entirely to thrive in it at the expense of those who suffer because of it.

This essay likely reads like the disordered ramblings of a lunatic who sees malice and injustice everywhere he looks and where those on high exploit the low as part of nature’s designs. It is healthy to be critical. We make improvements by asking questions. It is limiting to poll only those who are satisfied and far more insightful to ask questions to those who are not. However, whenever someone expresses outrage at the injustices brought about by modern systems and institutions they are then tasked to provide a suitable alternative. When the high is left to examine any alternative, they pull it apart and subject it to unfair scrutiny pulling it off the table and dismissing it outright precisely because it cuts into their station – which is exactly the point. The result is that history has shown that the best we have come up with to flip the script is violent revolution. Once again, where it matters, we are a species short of ideas.

My dream is for a world where two and two may equal five without consequence. When wrong ideas are benign, those who cling to them are just lone lunatics attempting to be heard in the vacuum of space. We are all just products of conditioning. No one is evil, we just get things wrong from time to time and no one wants to admit that they are wrong. Socrates was decreed by the Oracle of Apollo to be the wisest man in antiquity. When asked about it, Socrates admitted that the reason why was because he alone had the good sense to understand that he knew nothing. Humility is virtuous and there is little harm in beginning from the premise that all that you believe may be erroneous. Get comfortable with being wrong and allow others room for their bad ideas because fucking up is preferable to a lie. Humpty Dumpty can be put together again – it simply requires more horses and more sensible and cooperative men. Once you tell even one lie, then every word you utter after is subject to scrutiny. Real evil is in the unfeeling spreadsheet and the mind of someone stuck on the idea that numbers must always trend in one direction. Nature is fluid and rigid thinking attempts to build a dyke to break the waves instead of handing us all a surfboard to enjoy the ride. Cranberry juice should be made from cranberries and a ‘cancel’ button on an elevator is a great idea. And, if not, no one is getting hurt. Above all, it’s okay to be wrong. After all, there is a strong likelihood that none of this real anyway.