Comuna 13

Colombians are tired of violence. These were Rafa’s words to me when I inquired about security in Colombia. If I was going to be travelling the length of the country, I was keen to avoid problems. Normally, when people ask me about security in the many strange places I visit and whether or not I ever worry, I respond confidently that I, with my long hair and beard dangling to my chest, am what most people are afraid of. But Colombia’s reputation for violence stretches back a century and, though the war on drugs has been largely mitigated, small bands of criminal and paramilitary groups still exist on the fringes of society. Rafa admitted with humility that every family in Colombia had been affected by the violence caused by the drug war and the cartels. Cartels usually sprung up in small communities hoping to improve the lives of the rural poor, but their methods were illegal and founded on intimidation and violence. The government used equally brutal tactics to suppress them and interfere with their interests. It didn’t matter who was more helpful to you, or whose side you might be on, you had your own story about how one or the other combatting factions got close to you. Either you were in the car when your father was forced at gunpoint to courier a wounded soldier to the nearest hospital, or you watched your mother break down in tears when receiving the news that your cousin’s body had washed up on the shores of the river.

Medellin was a city at the very heart of Colombia’s drug conflict. Home to the country’s most notorious drug lord, Pablo Escobar, the city carries with it forever the stain of Colombia’s legacy of crime and violence. As a result, the city has become the centrepiece showcasing Colombia’s recovery and the country’s fastest-growing urban economic centre.

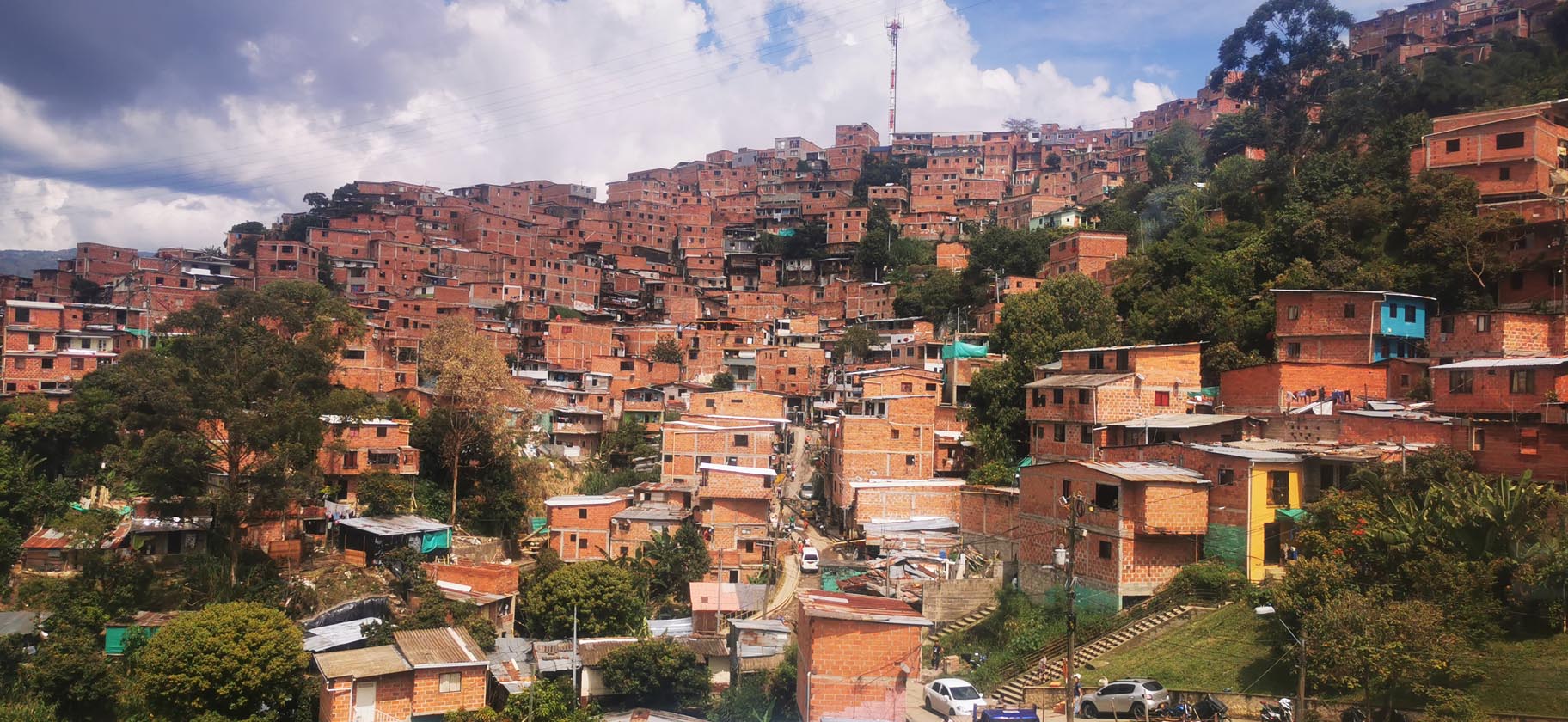

Sandwiched on the east and west by mountains, the city is built on either side of the Medellin river, a tributary of the Magdalena, which runs from south to north. The modern metro’s main line runs right along this river with several smaller lines branching off and connecting the various barrios that flank either side of the river. The city keeps expanding outward into poorer neighbourhoods that are built along the hillsides and accessible by cable cars. One such neighbourhood is San Javier, or Comuna 13.

Sandwiched on the east and west by mountains, the city is built on either side of the Medellin river, a tributary of the Magdalena, which runs from south to north. The modern metro’s main line runs right along this river with several smaller lines branching off and connecting the various barrios that flank either side of the river. The city keeps expanding outward into poorer neighbourhoods that are built along the hillsides and accessible by cable cars. One such neighbourhood is San Javier, or Comuna 13.

Comuna 13 has long been one of Medellin’s poorest communities. During the height of his influence, it was these poor communities that Pablo Escobar targeted both for his philanthropy and for his criminal enterprises. With the money he made trafficking cocaine, Escobar used the money to build roads and powerlines and housing communities for people who had long been living in garbage on the city dump. Escobar’s policy of Plata o Plomo, silver or lead, became a terrifying catchphrase as a threat to anyone who interfered with his trafficking empire. On a macro level, the greatest threat to Escobar’s interests was the government legislation passing through the Colombian parliament that would have allowed Colombian nationals to be extradited for crimes in other countries. Facing charges in the United States, and eager to avoid serving a lifelong prison sentence in an American jail, Escobar entered politics where he bribed or murdered judges and bought off and intimidated other politicians in order to keep the extradition bill from passing. On a micro level, Escobar employed street thugs and enforcers and drug mules to move product through their communities that would eventually make their way overseas. Anyone who got in his way either paid up or paid the price. His drug empire amassed an estimated $30 billion making him history’s wealthiest criminal and he is alleged to have personally murdered, or ordered the killing of, roughly 4000 people.

The street thugs that Escobar hired tended to come from the urban poor and Comuna 13 became a breeding ground for those who were willing to commit murder in order to escape from their desperate situation. During the 1980s, Colombia’s homicide rate skyrocketed leading to Colombia garnering its reputation as the most dangerous place on Earth. Its key contributor to that dubious distinction was Comuna 13 and other impoverished barrios like it.

Citizens of Medellin, instead of shying away from their sordid history have decided to steer into the skid. Comuna 13 is stacks upon stacks of clay brick boxes rising up the mountainside as a maze of narrow alleyways and staircases wind their way between the small homes and shops that have piled up on one another. In 2011, the government installed an outdoor escalator allowing residents to more easily travel on foot from the base of the mountain to their homes at the top that overlook the city. The escalator soon became a tourist attraction and the neighbourhood quickly noticed that tourism, not drugs, was a more sustainable way to bring in money.

Citizens of Medellin, instead of shying away from their sordid history have decided to steer into the skid. Comuna 13 is stacks upon stacks of clay brick boxes rising up the mountainside as a maze of narrow alleyways and staircases wind their way between the small homes and shops that have piled up on one another. In 2011, the government installed an outdoor escalator allowing residents to more easily travel on foot from the base of the mountain to their homes at the top that overlook the city. The escalator soon became a tourist attraction and the neighbourhood quickly noticed that tourism, not drugs, was a more sustainable way to bring in money.

Today, Comuna 13 is a thriving urban cultural centre where the most barbaric form of violence you are likely to see is a dance-off. Street sellers and shop owners proudly wear t-shirts that say: “Born and Raised in Comuna 13”. Agencies offer graffiti tours and there are rap battles going non-stop in the plazas and covered tennis courts. Speakers from every pub compete to be heard pumping out the latest hits from the cumbia and reggaeton charts. Drugs might be hard to find, but family-friendly homemade ice cream shops are on every corner. It is difficult to walk 50 paces without running into a souvenir shop selling any number of items designed to remind people that Comuna 13 once was, but is no longer, renowned for violence. Comuna 13 is now also the ultimate home for local artisans and their crafts from threads and jewellery to every canvas imaginable.

In the last decade, Comuna 13 has transformed itself from a place where residents feared stepping outside their homes to one where people from everywhere around the world flock to just to stroll through the streets without a care in the world. Watching the news it can sometimes seem that we are keener to play see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil when it comes to humanity’s shamefully violent history. Instead of owning up to our failures, we tear down the statues of our not-so-glorious past. I remember strolling past the blasted-out ruins of Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church and understood right away that that ugliness stayed preserved by its people as a reminder that they would never again allow themselves to be seduced by the fascism and tyranny that wrought so much destruction. Similarly, the true Colombian spirit of joy now wells up from the remnants of this once darkest corner of a city where evil was allowed to flourish. And it is not in spite of its history of violence that Comuna 13 has rebounded the way it has, but because of it. The entire neighbourhood has become a never-ending street party and a symbol of what happens when the human spirit grows tired of violence.