HES Code

There is an unshakable unease that comes with crossing a border. Some border guards are welcoming and full of cheer while others are sullen and appear to be carrying the weight of the world. There was a time when waiting in line at customs brought more nervous anticipation than it did dread, but the pandemic has changed everything. Now, there can be subtle differences in the rules depending on whether travellers are arriving on land or by air. Rules can change when you are in transit. Rules differ depending on where you are arriving from regardless of what the rules might say for the passport you hold. If international travel was complicated before, in 2021 it is a mess. More than two hundred countries and independent principalities in the world and, even with a cooperative body like the WHO, each one feels it knows best when it comes to both the severity of the virus and how best to protect its citizens. The result is a jumbled mess of legalese that may, or may not, apply to citizens and foreigners who wish to enter or move between jurisdictions of any given country. In many cases, all that jargon seems designed to confuse and intimidate would-be travellers with the hope that they will just plum give up and stay at home. Rules are often arbitrary, or unnecessarily punitive, or designed to spread around whatever little tourism wealth that might still be flowing. In some rare instances, governments and technology companies work together to devise solutions designed at mitigating the spread of the virus that seem almost too sensible. One of these twenty-first-century solutions is Turkey’s HES Code.

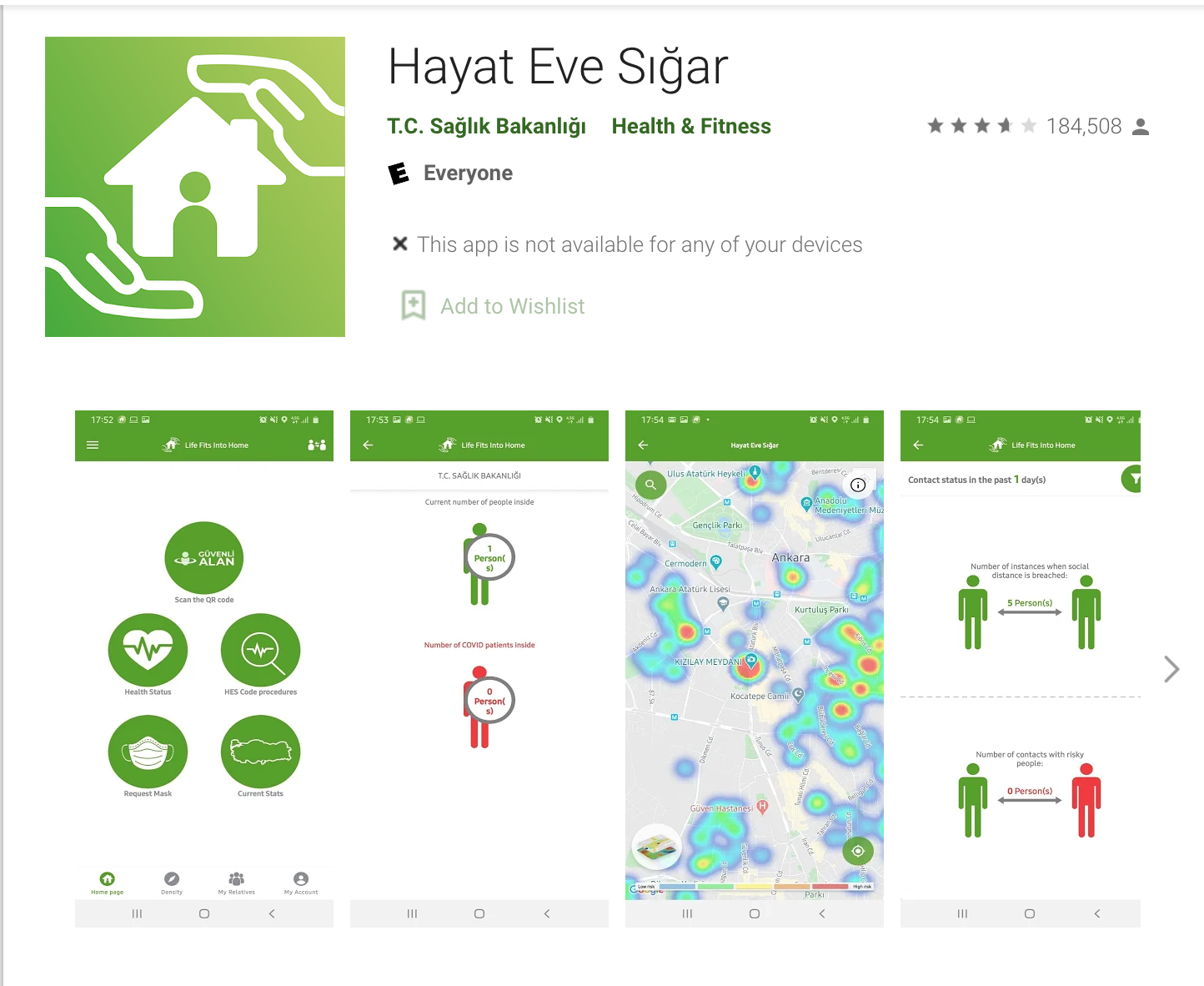

The Hayat Eve Sigar (HES) Code is part of the Life Fits Into Home program – a smartphone app available on both Google Play and the Apple Store. It is a lifestyle tracking app that is required by Turkish citizens and visitors to Turkey who wish to use hotels and restaurants and travel within the country. The design was simple: each citizen inside Turkey has a registered number that corresponds with their driver’s license or other legal documents and a barcode associated with that number. Businesses and public places have their own codes as well and it is a simple matter of scanning codes wherever you go. The app also collects hospital and testing centre data and aggregates that information with areas around the city that correspond with the HES Codes of individuals that test positive. Using this data, within the application, users can view maps of areas that might be considered high-risk. The application also contains important information about covid-19 transmission, how to self-assess symptoms, and what to do if you suspect that you, or someone in your household, may have contracted the virus.

As far as tracking apps designed at promoting public health are concerned, Turkey’s HES Code program was an ambitious undertaking with one clear objective: to mitigate the spread of the covid-19 pandemic. But like any ambitious undertaking, it could only be as successful as its users’ cooperation would allow. Bureaucrats in Ankara were no doubt pleased with their invention and would use it as a political tool and symbol of progress made by the present administration at protecting Turkish citizens during challenging times. The pide and döner vendors on the streets throughout the country have different ideas and different priorities that have nothing to do with politics.

I first heard of the HES Code when researching entry regulations to Turkey. When I purchased a SIM card at the airport, I had the attendant register a HES Code for me. In order to take the tram from Taksim to Sultanahmet, I required a HES Code to purchase an Istanbul transit card. While walking through Karaköy, I tried to enter a high-end shop and was required to scan my HES Code. In Istanbul, a city still with so much hustle and bustle in spite of rising case numbers, that was the extent of the role that the HES Code played. Both were instances that were completely avoidable had I decided to take a taxi or just keep walking.

In the capital, it was a different story. Traffic through the city centre was reduced to a trickle with police checkpoints at various intersections throughout the city. Compared to most Turkish cities, Ankara is far less walkable but foot traffic seemed to have almost completely disappeared. Compared to Istanbul where, but for a few restrictions, life seemed open and ordinary, Ankara was closed for business. Few shops remained open. Every pedestrian walked the street wearing a mask and the mood felt tense. Checking into my hotel in Ankara took over a quarter of an hour. It was one of a few hotels still open in the downtown area but still had only a few visitors. There were extended waits during the check-in procedure to scan and photocopy various documents and it was the only hotel in the whole country that ever asked me to present my HES code.

Cases peaked in Turkey during my visit rising to as high as an average of 60,000 cases per day. The country underwent its heaviest lockdown since the start of the pandemic by heavily restricting the movement of Turkish citizens during the holy month of Ramadan. It encroached into the lives and happiness of all of its citizens, but it never dampened their hospitality. And, other than requiring it to fly back to Istanbul, the HES code barely played a role in determining where I could go or what I was allowed to do. A month passed with 300 people dying each day of the virus while this device lay dormant and its potential wasted.

Cases peaked in Turkey during my visit rising to as high as an average of 60,000 cases per day. The country underwent its heaviest lockdown since the start of the pandemic by heavily restricting the movement of Turkish citizens during the holy month of Ramadan. It encroached into the lives and happiness of all of its citizens, but it never dampened their hospitality. And, other than requiring it to fly back to Istanbul, the HES code barely played a role in determining where I could go or what I was allowed to do. A month passed with 300 people dying each day of the virus while this device lay dormant and its potential wasted.

Perhaps it was an opportunity lost. What was revealing was that, outside of the capital, it was Turks, the folks on the street, who were going to determine how to mitigate the spread of the virus and not a technology designed specifically to help them do so. Government assistance and working from home are not options afforded to many Turks who rely on the bazaar and the in-person interactions of the streets to strike deals and move the economy. Those old ways are still what put roofs over their heads and their children through school.

As a tourist, Turks were happy to see me and I was afforded rights that they were not. They understood what visitors brought to their economy and hawkers and souvenir dealers in Istanbul and towns across the country were now struggling not just with the decline in tourism but with being forced by the government to close their shops. Every restaurateur was at the ready to help and if they could not provide something they knew how to work within the community to get what was needed and spread the wealth. Every little bit went a long way. No tracking app could account for all of the tiny underground networks woven together like a net that prevented the country from falling into the ocean.

How many lives might the HES Code have saved? Certainly, there is a government-appointed epidemiologist in charge of assembling a team designed to answer that question so that the current administration can have it at the ready come election time when they face criticism and the inevitable vote. Western governments have been calling for a change in leadership in Turkey for several years and feel that Erdogan’s grip on power has become too authoritarian. Elections are scheduled for 2023 where the ruling Justice and Development Party will look to control a majority of seats in parliament. What role the handling of the pandemic might play in determining the outcome of that election will have to wait and see but every state inevitably staring down the barrel of political change will put the ruling party through scrutiny over how they handled the pandemic. In the end, the outcomes at the ballot box will have less to do with real results and more about the trust that citizens put in their government.

As countries endeavour to roll out their vaccination programs and race toward herd immunity – a strategy widely regarded as the only viable solution to the problem – huge swathes of the citizenry are contending with new ways of being monitored and controlled in the name of public health. Those holding public office see their efforts and the mandates that they impose as sensible measures designed to promote the well-being of all citizens and their democracy. But they do not walk the streets. They do not know the mood of the common man and woman who sets out on foot to the market for bulgur and rice. Many skeptics among those ridiculed and derided in the liberal news as anti-science conspiracy theorists are not motivated by an aversion to technology but by a failure of their government to consider other options. They are everyday people leading everyday lives who are too busy and have their minds on more pressing matters because the alerts on their smartphones will not boil soup. They are not enemies to public health because the HES Code, nor any heavy-handed government mandate, can solve the underlying problem that many must defy public health initiatives just to survive.

When Western liberals bemoan anti-vaccine sentiment they chalk it up to right-wing conservative stupidity and a failure of the education system to offer all students a firm footing in science. It has little to do with the education system itself and more to do with first, access to that system and second, mistrust in the institutions that have failed them time and again. HES Code is just another in a string of government programs aimed at pruning a dead tree without having to examine the roots – it is a wonderful idea in theory but useless in practice.