The Dandelion Has My Smile

I arrived in Lumbini with a copy of Thich Nhat Anh’s, Peace is Every Step, an open heart, an open mind, and an inspired reverence for Buddhism. Stumbling off the bus from Bhairahawa at the Lumbini Bazar in the early evening, I trudged through the muddy streets that border the monastic zone and made myself comfortable at one of the local hotels.

In 563 BC, Queen Mahamayadevi gave birth to Siddhartha Gautama who achieved enlightenment and became Buddha. All of Buddhism, one of the Earth’s oldest religions, traces its roots to here. The centre of Buddhist pilgrimage is at the Maya Devi temple on the southern end of the complex.  Inside there are ruins and a stone dedicated to the Buddha and the site of his birth where pilgrims can leave offerings. A manmade canal runs down the centre of the complex with Buddhist temples funded by various Buddhist associations from around the world on either side and visible at the far end two kilometres away is the World Peace Pagoda. Vishnupura road is the rectangular loop that defines the borders of the pilgrimage site.

Inside there are ruins and a stone dedicated to the Buddha and the site of his birth where pilgrims can leave offerings. A manmade canal runs down the centre of the complex with Buddhist temples funded by various Buddhist associations from around the world on either side and visible at the far end two kilometres away is the World Peace Pagoda. Vishnupura road is the rectangular loop that defines the borders of the pilgrimage site.

I woke up bright and early and put my work aside to be able to spend my day in the complex and at peace. I was one of a handful of foreigners who had come this way and who stood out among the area school groups and genuine Buddhist pilgrims who had come from India, China and other parts of Nepal. There was a persistent haze that hung over the town the entire day and the air was thick and muggy and down in the valley toward India and, away from the mountains to the north, it was hot even in the shade.

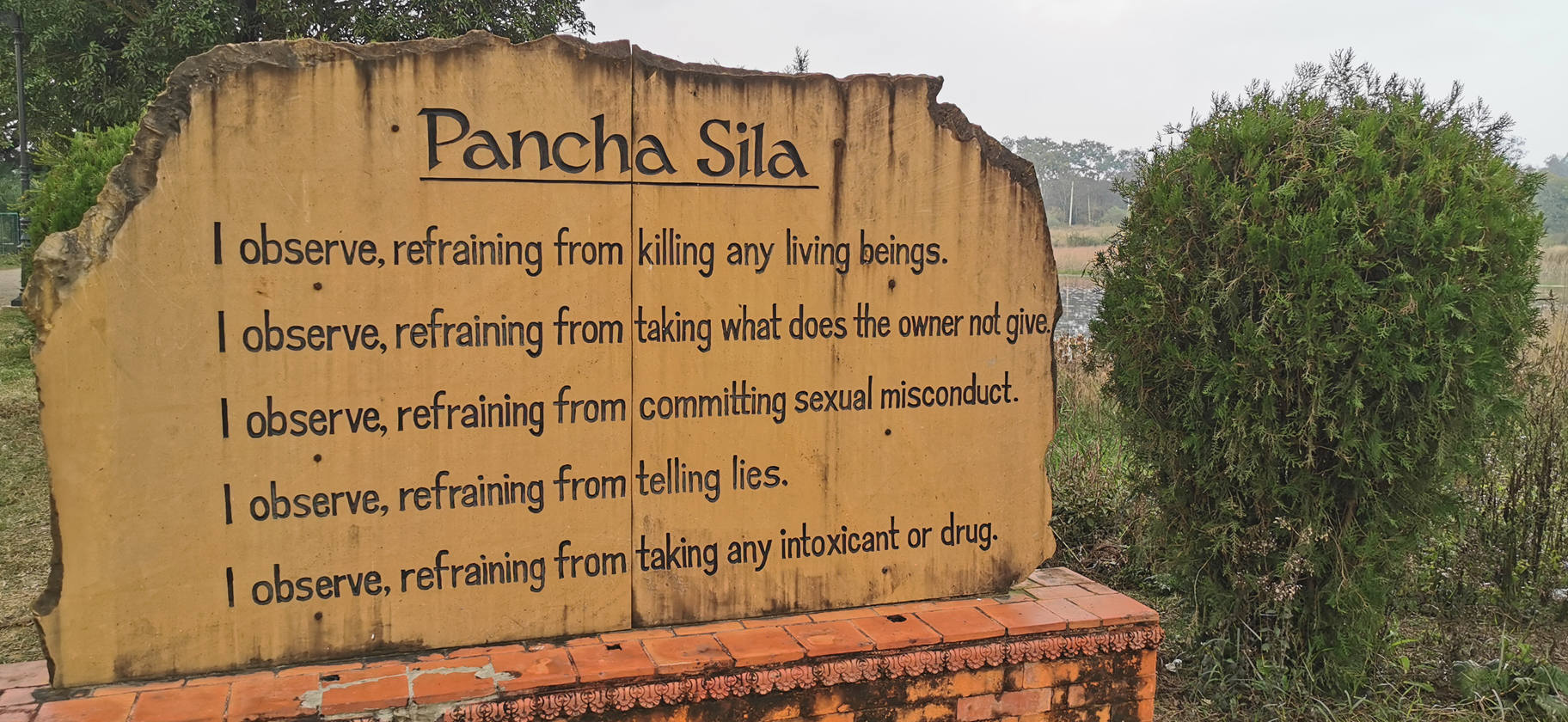

Inside the gate, monkeys hopped about in the trees and on the benches looking for scraps of food. A few of the neighbourhood homeless had set up shop and were begging for change. The thickets and grass were overgrown and real maintenance on any part of the complex outside of the Maya Devi temple had been neglected for years.  Just before entering the inner part of the complex, there is a sign with the basic tenets of Buddhism written on it, and just past the sign is the pathway to the temple.

Just before entering the inner part of the complex, there is a sign with the basic tenets of Buddhism written on it, and just past the sign is the pathway to the temple.

On my walk, I visited as many temples as I could. Some are large and well maintained and can draw a crowd. Some are more understated and tricky to get to as they may only be reachable by carefully navigating down a flooded alleyway of mud and dirt. Some are dilapidated messes that have no entrances and look as though they have been abandoned.

Shoes need to be removed when you enter any of the temples. Though it was hot outside, inside the temples it was always dark and cool. In each temple, there are bronze statues and colourful wreaths and banners with symbols of the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum – the sacred jewel lotus of enlightenment. Many of the temples also have living quarters both for monks and pilgrims. Rooms and facilities are as basic as you get: four walls and a roof and shared facilities for doing your business.

Peace is Every Step was a small treatise with reflections on ways to better communicate with the world and discover a better sense of inner wellbeing. It didn’t take long for me to reflect on many of its messages and regard it as a bit cornball and not self-aware enough to offer practical advice on how to actually parse through the challenges of the modern world. In the book, there were messages like managing anger by making an effort to smile more or how to find peace by going in search of peace. It was all a bit flowery and utopian but not necessarily insightful or able to stimulate real thought and reflection. It did venture into ideas on connectedness and interbeing but only as far as to say that we are all of the same stuff and that all of the blades of grass and all of the animals, as we and they are all part of this world, are all one.

I am not sure what I was expecting, but perhaps there was something about the spiritual, stripped completely of the scientific, that felt too much like greeting card wordplay and not enough like real wisdom. In a certain few of the temples, there were plaques on the wall with translations into English of certain tenets of Buddhist thought, such as:

“Those who know the essential to be essential and the unessential to be unessential, dwelling in right thoughts, do arrive at the essential.”

I did not find this kind of insight to be clever.

I was anticipating that the Buddhist temples would be calm and contemplative places that would be welcoming of those seeking a quiet moment of thoughtful reflection. Instead, they were not much more than symbolic showpieces for the religious side, and less the spiritual side, of Buddhism. Meditation and prayer did not seem like activities that were on the agenda. Instead, small crowds would get ushered around to each temple, enter, take a few pictures, slip a few notes into the donation box, and move on. These crowds meant that there was always a good deal of traffic to navigate through and that also served to disturb the peace.

I was anticipating that the Buddhist temples would be calm and contemplative places that would be welcoming of those seeking a quiet moment of thoughtful reflection. Instead, they were not much more than symbolic showpieces for the religious side, and less the spiritual side, of Buddhism. Meditation and prayer did not seem like activities that were on the agenda. Instead, small crowds would get ushered around to each temple, enter, take a few pictures, slip a few notes into the donation box, and move on. These crowds meant that there was always a good deal of traffic to navigate through and that also served to disturb the peace.

My frustrations at achieving enlightenment were further confounded by my seemingly celebrity-like status. All I wanted to do was blend in and disappear, but other visitors were not shy about asking me to take selfies with them. Most were simply captivated by the presence of someone who had obviously come from so far away and a country and a world that they had only ever seen in the movies – but I was no movie star, I was just a guy. Though they were brazen, I knew that they were also harmless, but I could not wrap my head around the idea that a photo with me would seem so interesting. Within seconds of snapping a photo, it was up on the Gram. I was the big event, not the holy ground upon which we were walking. My 40 years of obscure existence at that moment trumped 2,500 years of sacred space.

We have a remarkable capacity to ruin beautiful things through our reverence for their beauty, and somehow I could not help but feel cheated and deprived of the wisdom of Buddha by what the religion he begat had become. There was something unnaturally glossy about these temples. The ones that were maintained brought visitors and visitors brought tithes that could pay for the temple to be maintained. It was a cycle that perpetuated its existence, but there was no longer any space to just be. The temples that nobody visited fell into disrepair and could no longer be visited. It seems we humans are only inclined to enjoy what others already enjoy. If it is not already praiseworthy we are skeptical and reluctant to deem it so. This has become our new notion of interbeing and we have conflated this idea with belonging. In much the same way that these kids hoping to have their picture taken with me knew that that photo could win them followers, so would their sense of belonging and interbeing rise with every ‘like’. Following, and being followed, has become the new “one with all things” and connections are the new interconnections. The more connections you have the more enlightened you become and the deeper your sense of interbeing.

There is a brand new world out there and the old wisdom seems to have abandoned its time in the sun. Thich Nhat Anh, in teaching about peace and interbeing, was speaking from a moment in time where his thoughts and ideas were relevant for a brief flickering moment. It seems that people are now relentlessly seeking connectedness with ways of achieving it thanks to tools that the Buddha could never have imagined. The peace required to achieve enlightenment, however, has also gone.