The Match – Imagining Peace in Liverpool

The world collapsed on December 8th, 1980.

After travelling up to Chester I decided to spend a day in nearby Liverpool and on the train ride up I spent most of my time learning about the city and thinking about what I should get up to. Given my football fandom, and the fact that they had just won the UEFA Champions League title, a trip up to Anfield seemed on the cards. I arrived early in the day and, at the time, there seemed to be plenty of the day left for all that, so upon pulling into the station I headed down to the Mersey for a look around. I meandered through the streets that ran from the station to the port where the ferries docked and tucked into a Fab Four shop to check out some fun Beatles memorabilia. Right next door was the museum of Liverpool and I don’t usually indulge in such things anymore, but there were no lineups and the admission was free so why not. That’s when I got waylaid by something far more important than football.

Now the story I grew up with was that Yoko Ono was the one responsible for breaking up the Beatles. In music circles, it was considered one of the great tragedies to befall the industry and robbed generations of rock n’ roll fans of the countless unrealized treasures that the Beatles would certainly have bestowed upon the world. Visiting the Double Fantasy exhibition on the top floor of the museum I realized that Yoko Ono did not rob us of the Beatles, she gave us the gift of the real John Lennon – a modern symbol for the artistry of peace.

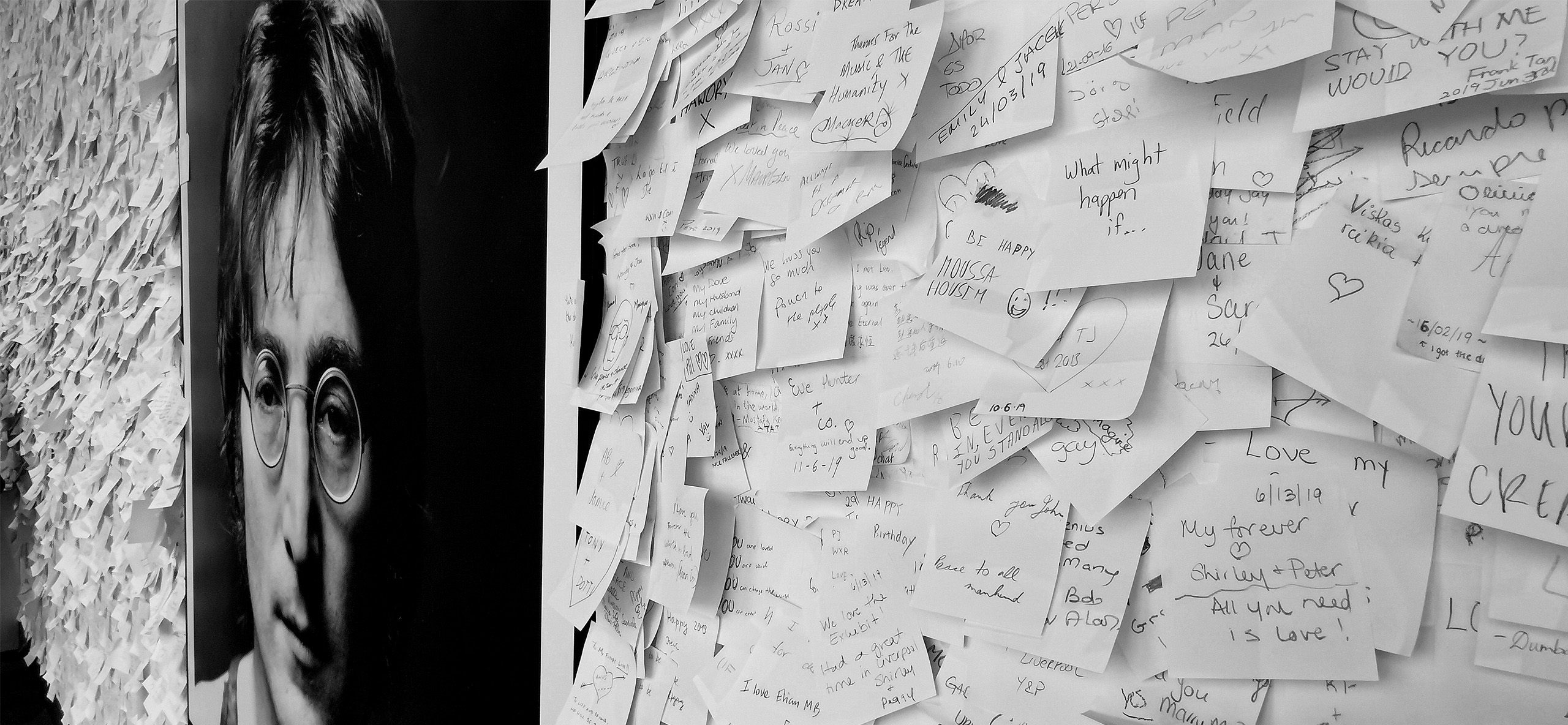

The contrast between the Fab Four shop and the museum exhibition could not have been more conspicuous. In the shop, every colour of the rainbow was on display hawking everything from t-shirts to coffee mugs to beach towels and even ashtrays. The Double Fantasy exhibition was nothing more than some old memorabilia, replays of old recordings, quotes on the wall, and stories about the couple all done in black and white. Out front was a box with the common reminder that the museum accepts donations.

While at the exhibition it is impossible to escape the song ‘Imagine’. It plays on a loop at the entrance and the music video plays on a loop in a small theatre. While walking through the exhibition and getting to know better the relationship that John and Yoko had, it is impossible not to think about other alternatives to the story that we have now. To suggest that John would have evolved into the person he became without Yoko is speculation. To suggest, further, that he would have been allowed to be himself as part of The Beatles is complete fancy. In fact, I will contend that the message of peace that we attribute to John Lennon is in fact the message of Yoko Ono channelled through John. If peace is the destination, John was the vehicle, and Yoko was the driver.

Of all the Beatles, it certainly seems, lyrically anyway, that John had a lot to say even if it seems he didn’t really know what he was ever really saying. By 1967, after famously stating that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus, John moved on lyrically from songs like a Hard Day’s Night and Ticket to Ride and wrote Strawberry Fields Forever about the orphanage for girls in the suburb of Woolton where he grew up. It was sobering subject matter to be sure, but it was all “nothing is real, and nothing to get hung about”. The compositions got more esoteric and complex as exemplified by the song A Day in the Life which strays from rock n’ roll and includes orchestral passages and a 15-kilohertz sine tone at the end that was inserted, apparently, to annoy dogs. Follow that up with I am the Walrus and musings like “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together” to which he later confessed that he was the Walrus and became John. Eventually, it was Come Together with words like, “He wear no shoeshine He got toe jam football He got monkey finger He shoot Coca-Cola He say I know you, you know me One thing I can tell you is You got to be free”. It would have been safe to say that in the late ’60s, the message was there even if it wasn’t exactly clear. The closest he came was probably with the song All You Need is Love which certainly strikes at the heart of what the world seeks, if only perhaps that in its joy it turned a blind eye to where the world was actually at – especially when it references the Beatles’ less sophisticated earlier work by introducing the hook to 1963’s She Loves You toward the song’s end.

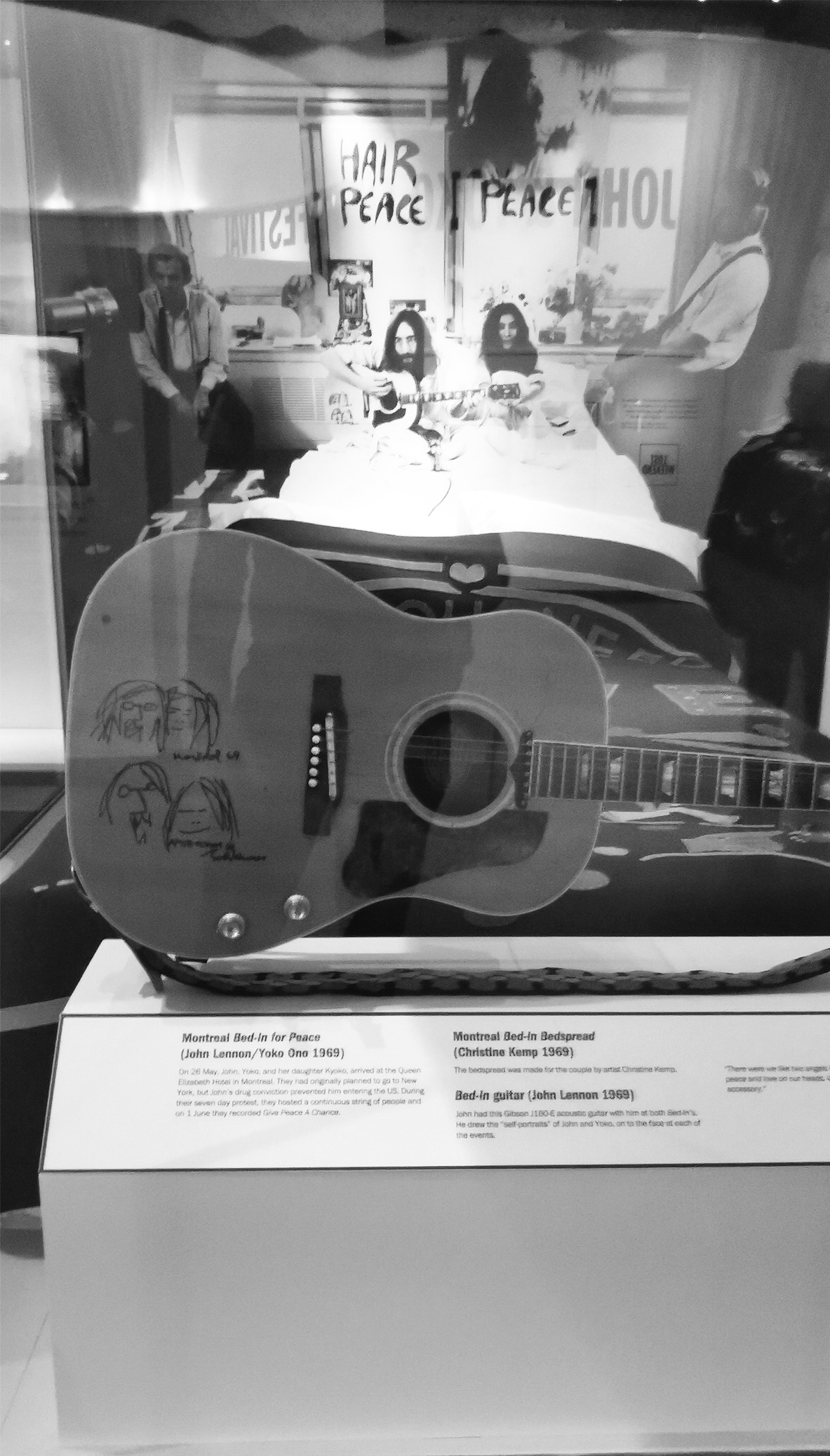

Clear in the work from John outside the Beatles is that the message is usually abundantly clear with no mishmash or wishy-washiness from his words, and it is obvious from the moment that Yoko appeared on the scene and they put together the song Give Peace a Chance during their “Bed-in” in Montreal while John was still a member of the Beatles. Often referred to as “anti-war”, if I had to sum up John’s (Yoko’s) core message it is “Pro-Peace”. In the song Give Peace a Chance the lyrics are as straightforward as they come: “People are talking about x, let’s talk about peace (paraphrased)”. Take a song like Instant Karma where you get lyrics like “Instant Karma’s gonna get you Gonna knock you right on the head You better get yourself together Pretty soon you’re gonna be dead”. Pretty direct, not to mention poignant given what would happen 10 years later. “Instant Karma’s gonna get you Gonna knock you off your feet Better recognize your brothers Ev’ryone you meet Why in the world are we here Surely not to live in pain and fear”. Unlike the dreamy poetry of his work with the Beatles, his solo offerings are almost so literal that they can be read as prose.

Clear in the work from John outside the Beatles is that the message is usually abundantly clear with no mishmash or wishy-washiness from his words, and it is obvious from the moment that Yoko appeared on the scene and they put together the song Give Peace a Chance during their “Bed-in” in Montreal while John was still a member of the Beatles. Often referred to as “anti-war”, if I had to sum up John’s (Yoko’s) core message it is “Pro-Peace”. In the song Give Peace a Chance the lyrics are as straightforward as they come: “People are talking about x, let’s talk about peace (paraphrased)”. Take a song like Instant Karma where you get lyrics like “Instant Karma’s gonna get you Gonna knock you right on the head You better get yourself together Pretty soon you’re gonna be dead”. Pretty direct, not to mention poignant given what would happen 10 years later. “Instant Karma’s gonna get you Gonna knock you off your feet Better recognize your brothers Ev’ryone you meet Why in the world are we here Surely not to live in pain and fear”. Unlike the dreamy poetry of his work with the Beatles, his solo offerings are almost so literal that they can be read as prose.

Strolling through the exhibition you eventually come to John’s last days where you read statistics about how many Americans have been killed because of gun violence since John’s murder, statements from his family days after the event, and old interviews of friends and family dealing with the aftermath ten years later. It’s sobering to realize that we live in a world where a man with that message can be taken from us that way. Humanity, after all, has a nasty record when it comes to murdering prophets. It breaks your heart.

To say I was affected by the exhibition would be an understatement. I left the museum and wandered through Ropewalks and straight out of town through Sefton Park to Calderstones and eventually to Strawberry Fields. You can grab a taxi that takes you to all the Beatles sights but I walked it. I’m told people don’t do that, but I was finally thinking straight. Better get yourself together Pretty soon you’re gonna be dead. John died when he was aged forty and sixty days. It hit me somewhere around Mossley Hill that my own fortieth year plus sixty would arrive in just 12 days.

Even with the museum far behind me, the song and the images from the Imagine music video kept replaying in my head until I finally realized what it was all about. How do you thank someone for helping you find yourself? How do you love someone who is lost? The exhibition made a few things very clear, one of them being John’s adoration and virtual deification of Yoko. So profound was it that even in a patriarchal world he took her name. John’s drug use may have opened the door to fantastical works of psychedelia and earned him a boat load of street cred, but it was Yoko that helped him kick the heroin addiction (see the song Cold Turkey for the details). We focus on the message and not his flaws, but Yoko had the emotional fortitude to forgive his “Lost Weekend” that lasted two years – we’re a disposable society and each of them had been married prior to meeting each other, and most people would have just moved on – but not Yoko.

The images in the video are the most revealing in the important role that Yoko Ono played in John’s message of peace that we all remember. It begins with them walking outdoors in a fog with their backs to the camera. They make their way to a beautiful mansion called “This is Not Here” and pass inside like spirits. The room is dark and the shadow of John sits at the piano in a dark and empty room as Yoko Ono begins to open the shutters on the windows to let the light in and finally revealing John’s face. Yoko continues to open the shutters to let more light in and it isn’t until she’s opened ALL the windows allowing in ALL the light and she sits next to John that her face is finally revealed. The song is drawing to its conclusion when John suddenly glances at her and she glances back. John looks back at the camera but Yoko’s gaze never strays. The song ends and John looks back at her again. The song is over, but the story isn’t. John makes a goofy face and they smile and kiss. The message is clear: he’s thanking her for lighting up the darkness so he can be honestly and truly seen.

Much maligned even to this day for the role she played in altering the course of the most beloved rock band that was ever formed, Yoko Ono has endured with grace and dignity the burden that a sick and twisted patriarchy has saddled her with and that was never her responsibility to bear. What she is never really credited with is charting the map for the voice of peace of an entire generation to cut a path that future generations could follow. To light a candle that illuminates a hall a sacrificial match is required before it is unceremoniously tossed away. Thank you, Yoko, for lighting the candle. All the shutters are open, I see your face.