The Smoke That Thunders

Debra wore a slinky pink dress that was designed to get my attention but was totally impractical for the activity we had planned. I had my hiking shoes on because it was all that I owned and because I told her that my reason for coming to Livingstone was to see the falls, which would entail a lot of walking. I had just had my initiation the night before into the challenges that parts of Africa face when the hotel I was staying at had no power all through the night and into the morning, right up until I checked out. That kind of situation forced me to find another hotel that had a generator and could guarantee that the lights would be on. Tourism was the way to pay for basics like electricity in Livingstone and I was about to find out why.

Debra was handy for negotiating a reasonable rate for a taxi to get us to the park, but there was no negotiating around the fact that the entrance fee was $20 dollars for me and only $2 for her. You learn pretty quickly, though, that all that money can’t make it rain.

The Zambezi River runs from the north near the Congo border and through eastern Angola and then turns eastward along the border of Namibia and northern Botswana. From there it heads along the south of Zambia and flows through Mozambique before it dumps into the Indian Ocean. It runs for some 2500 kilometres and is the fourth-longest river in Africa. The Upper Zambezi in the north and the Lower Zambezi that flows through Mozambique are divided by the Middle Zambezi which is where you will find the river’s most notable feature – Victoria Falls, or, as it is known in the local Lozi language, Mosi-oa-Tunya, “The Smoke that Thunders”. The river runs over a plateau and falls into a series of gorges that separate Zambia from Zimbabwe. In terms of height and width, it is nearly double the size of Niagara and dwarfed only by Iguazu Falls that borders Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay.

Debra and I entered the park and headed down to The Boiling Pot. As we descended the rocky steps the vegetation began to spring up and the vines and foliage dominated the landscape. In the jungle, troops of baboons scurried along the path looking for nuts and anything left behind by visitors. Eventually, we could begin to hear the first faint whispers of running water. A quaint little mountain stream turned into a creek and eventually after we had descended far enough it emptied into the river.

“Wow!” Debra cried out when we entered the clearing where the jungle ended and there was nothing but the view of the river and the gorge and the Victoria Falls Bridge that links Zambia and Zimbabwe.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“I haven’t been here in about 5 years, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen the river this low.”

She pointed to the lines on the rock left by the water from years past that indicate just how high the water level can get – at least 50 metres. We stopped by a small outcropping of rocks where you could sit in a small pool, like a bath, where the stream ran down into the river. I looked down hoping to get closer to the actual river but was prevented from doing so by a ranger who advised me that it was too dangerous to go any further.

“Normally the water reaches as high as this pool,” Debra said, but the river was another 100 metres below us.

We went back up to the other paths in the park that overlook the gorges and offer the best views of the falls. The trees were grey and dying and only the heartiest shrubs were still green and clinging to life on the plateau. The water that typically cascades over the falls was reduced to nothing more than a trickle. The summer rains that flood the plateau and water the crops were over a month late in coming and this section of the river was drying up.

“Oh my God! I think this is too dry!” Debra exclaimed.

I remember seeing an old photograph of a friend who had visited Victoria Falls about fifteen years earlier. He and his girlfriend were bathing in a pool along the river on the Zambia side where just a couple of metres away it spilled right into the gorge. There was no more pool, no more river, just a patch of thick mud.

Visiting the falls from the other side of the river in Zimbabwe painted a different picture of the situation. The park that peers out toward the falls is slightly further west and along a different, lower-lying, tributary. There is nowhere else for the water to go and so it all gets channelled along that avenue and plunges into the gorge below with a force that sends clouds of mist into the air and leaves a permanent rainbow arcing across the sky. All of its power and beauty are there to see and so close that you feel you can stretch out your hand and almost touch it. If this was all that you saw, you would swear that there was nothing wrong further down the plateau.

The town of Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe lies less than a kilometre away from the park and it has a number of fancy high-priced hotels and resorts to cater to wealthy visiting tourists. Livingstone, the town on the Zambia side, is located 10 kilometres away from its park. The park involves some effort to get to, but the hotels in Livingstone are cheap compared to Victoria Falls which are double the price for the same level of comfort. In the end, you kind of end up getting what you pay for.

The town of Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe lies less than a kilometre away from the park and it has a number of fancy high-priced hotels and resorts to cater to wealthy visiting tourists. Livingstone, the town on the Zambia side, is located 10 kilometres away from its park. The park involves some effort to get to, but the hotels in Livingstone are cheap compared to Victoria Falls which are double the price for the same level of comfort. In the end, you kind of end up getting what you pay for.

I have become accustomed to the lights being on. Where I come from the electricity just works and if there is an outage, it is repaired within a couple of hours. The price is so nominal and the electricity so essential that it is easy to forget that I pay for it and I almost never give a second thought as to how it gets from its source to the sockets in my home. It is built into every routine of daily life. Electricity powers the stove that heats my coffee pot in the morning; it charges my computer to which I am glued for most of the day working to earn the money to pay for the electricity to charge the computer; it powers the modem and the router to keep me connected to the world; it turns on the television and the lights when the sun goes down. There is scarcely a moment in my life when electricity is not being used.

What happens when the local infrastructure responsible for generating electricity cannot run? How often do we think about where electricity actually comes from? For those living along the Zambezi, electricity comes from the turbines at the power stations that convert the power of the river to electrical energy. But what happens if the river dries and cannot generate enough power to spin the turbines? This was the situation in both Victoria Falls and Livingstone. Local energy was not being produced because the rains had not come and the river had dried to such an unprecedented level that if the people wanted to have electricity they had to generate it themselves, or the government had to pay to import it. This is where the stark contrast between Victoria Falls and Livingstone was most palpably felt.

In Victoria Falls, where you can immerse yourself in that mystical experience of all of the glory of the falls, the hotels are more expensive but the lights stay on. In Livingstone, where the falls are not falls but just a patch of mud and a babbling brook, the hotels are cheap but the lights may, or may not, work. It needs to be said as well that Victoria Falls and its ability to provide continuous electricity is not representative of the situation in Zimbabwe, but only of the town itself where Victoria Falls is like a country within a country. And where money flows, the ones with the money can turn a blind eye to any problem.

The local people in Livingstone were experiencing a situation that was not normal for them. Looking at a list of countries ranked by GDP, of the bottom 50 in the world 34 are in Africa – Zambia and Zimbabwe among them (only 5 African nations report a GDP above the world average – Seychelles, Mauritius, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and Botswana). It’s easy to think of poorer countries having major economic challenges like energy insecurity, but when the people in a major centre like Livingstone are remarking, “no brother, this is fucked up!” you quickly realize that something else is at play.

I often find it interesting how many people believe, and spread the message, that man-made climate change is a hoax. All of those I know, or have met, that think this way have one indelible trait in common – they are unaffected by climate change. They were the ones that could fly to Victoria Falls, stay at a fancy hotel, gaze upon the falls, return to wherever they were from and experience a cool crisp day, and think that nothing was wrong. But try sitting in the darkness, drenched in sweat because you can’t run the air conditioning or even a fan because the river is drying up and your country is too poor to purchase electricity, and then tell me that everything is hunky-dory. I went just about bat-shit crazy after just 24 hours, but the locals live with it every day. This is the twenty-first century and the challenges faced by the third world that we used to bemoan thirty or forty years ago are not the challenges they ought to be facing today. Electricity has come to southern Africa and has been around for quite some time, but for the time being, climate change and an inability to get the world’s attention has robbed them of it.

Zambia is a perfect place for a pilot project for building small, local, and sustainable energy infrastructure like solar power. However, due to corruption, the wealthy can pay to import their electricity (usually dirty) while most other folks are living day-to-day and too poor to invest the estimated $5000 to have a solar-powered system installed including the panels, converters and battery, for their home. Well aware that there may be no tomorrow, many people I met abide by the idea that it’s better to eat today than worry about all tomorrow’s meals. Five thousand dollars is also a number so grotesquely high for most people that to hold off on buying so many of life’s necessities in order to save for a problem that could be solved by government involvement – if they ever got their shit together – by the time they are able to save enough is nothing more than hedging one’s bets.

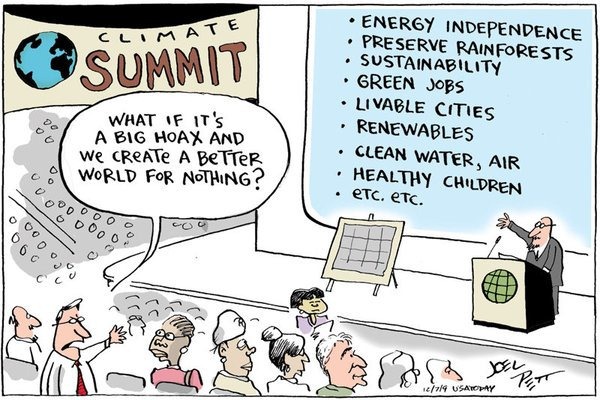

In the arguments concerning climate change, the positions are so polarized between doomsday scenarios and complete rejection of science and facts that the pursuit of better living for everyone gets killed in the crossfire. I’m reminded of a cartoon I saw once where, at a climate summit, someone has stood up to address the speaker and asks, “What if it’s a big hoax and we create a better world for nothing?”  Why is it that when it comes to solving climate change we seem only interested in not having global temperatures rise to such a high level that the polar ice caps melt, all the rivers dry up, and civilization comes to its catastrophic but inevitable grisly conclusion?

Why is it that when it comes to solving climate change we seem only interested in not having global temperatures rise to such a high level that the polar ice caps melt, all the rivers dry up, and civilization comes to its catastrophic but inevitable grisly conclusion?

In Canada, we have a strong economy, rich natural resources, and social programs designed to keep our living standards at a certain level. Still, even we balk at the business of having to make economic sacrifices for the greater good. Many countries don’t have it as well as we do. I’ve dodged many a heap of garbage in the streets of Cairo, emerged from the ocean onto sandy beaches around the world with tattered chip bags clinging to my ankles, and walked through the streets of many major cities barely able to breathe from industrial pollution. To someone from a place as green-conscious as Vancouver, it’s an annoyance from the touch of culture shock I had to endure by travelling to an exotic locale, but for people from those places that is life. Caring about the climate shouldn’t just be about preventing the end of civilization. Caring about the climate should be about making the best and most economical use of the resources we are given to make the world a pleasant and enjoyable place to live for every living thing on it. Pollution of any kind, whether as impactful as heavy industry or just needlessly neglectful as tossing a cigarette, should be frowned upon because there’s always a better solution if you just put a little energy into caring.

When I was about 10 years old my family travelled to Daytona, Florida. We took a special trip to visit the race track where they race the Daytona 500 and where, at that time, they were conducting time trials. It was a pretty sedate scene by comparison to the spectacle of a big race, but seeing the size of the track for the first time and hearing the roar of the engine from a car speeding around the track was an awesome sight. My youthful mind was seeking spectacle and, in its exuberance, I remember shouting out how amazing it would be to see a crash. My mother grabbed me and with a look that was both stern and disappointed said, “there is a human being driving that car!”

More than the words themselves it was the look in my mother’s eyes when she spoke them that still haunts me. It was a kind of not my son sort of look that I felt that from that day forward, through my actions and my words, I would spend the rest of my life trying to make right. In fact, there are people behind everything we do. When you pass a block of flats in some nameless town that you can’t even pronounce and dismiss without a second thought, that is a place that someone has, for one reason or another, decided to call home. They are sharing meals, throwing parties, trying to improve the quality of their days and nights, growing old, growing up, and falling in love in those places with just as much right to breathe clean air as anyone.

Debra, in her slinky pink dress, might have had other things on her mind than arguing over the merits of arguments from either side of the climate change debate. She could not see the couple from California on holiday across the way in Zimbabwe enjoying the cherry on top of their dream vacation to the rugged wilds of Africa. She had a child to raise. Your notions of a dream vacation are vastly different when you’re strategizing around when the electricity might come on again so a load of wash can be done; or how to get enough wood to make a fire to cook a meal because the hob won’t turn on. I don’t know when the rains were going to come again and raise the level of the river to be able to spin the turbines and bring power back to Livingstone, but Debra was a human being and yes I did notice her in that dress and I worry about her.

My grandmother, who witnessed her share of twentieth-century atrocities, once shared with me that the worst thing in life was to bear witness – to watch the horrors unfold and be powerless to do anything about them. She shared the sentiment with me on a few occasions each time with a quivering lip as though there were more to say on the matter but she could not tell me, perhaps unable to find the strength to speak the words. To live in these times now and wonder how and why it has come to this for so many people who deserve better and have been disavowed by the people who can help and change their lives for the better, I begin to sense what my grandmother meant.

Still it’s the voices of those who cannot see that bellow loudest as the river dries and the falls recede. One day the smoke may no longer rise and no longer thunder, but for now my friends don’t know when the lights will come on and that’s not okay with me. Regardless of our impact on the climate I just want them to have what they need. I would like the view from both sides of the gorge to be just as stunning and I would take great pleasure in creating a better world for nothing.