The Wait – Perceptions and Geopolitics of Tiny Hungary

I have often called my mother and her generation the “Cold War Kids”. There was something about growing up in the 50s and 60s that made people more prone to gossip. They were secretive and suspicious and they were keen to pass on a heightened sense of security to their children which is why my generation grew up with the slogan “never talk to strangers”. As we entered the information age at the turn of the last century the values changed – the switch flipped – and suddenly our whole lives were being shared, with the click of a button, to the entire world. Nowadays we are inundated with ways to share information, thoughts, feelings, and reach communities of people like never before – inconceivable only a few decades ago; dangerous if, like my mother, you were born in communist Europe.

Both of my grandparents’ familial houses were of independently wealthy landowners under the monarchy and had re-established themselves between the wars and after World War II, but by the end of the 1956 revolution when the communists seized control, in secret documents revealed to my grandfather, our family was deemed by the communist party as unreliable. The consequences of such a label by the party were uncertain, but often a matter of life and death. Stories of torture and execution were common and well-founded. People disappeared. This meant my family had to flee across the border to Austria and become refugees where they were eventually welcomed to begin again in Canada. My mother’s family integrated into Canada and became a success, and in every sense of the word, my brother and I and our cousins are Canadian. Our Hungarian heritage is something we cling to, however loosely, when it feels convenient, but our world view is a world apart from my grandparents and the country that they left behind.

* * *

Magdi’s house in Mátyásföld has always been a good base for all of my visits to Hungary. There is plenty of room and Magdi is a gracious host who takes good care of me and also knows how to let me have my space. When I left Magdi’s house to and go explore other parts of Hungary, one of my first tasks was to purchase a new prepaid phone card. The first 24 hours without being able to connect to the network was the most difficult because of how isolated I felt. Being able to connect to the internet and get information up to the second was how I was able to stay on top of all of my projects and keep my business running smoothly, so a full day without being able to send and receive emails gave me anxiety. Typically, when purchasing a new prepaid phone card, I would be able to connect before even completing the transaction. I got into the habit of restarting my phone every couple of hours, but there was still no signal. By the second day without service, I finally got a call from customer support and they said, with no justifiable reason as to why, that it could take up to 15 days to connect. At this point, I just wanted to cancel my service, get my money back, and move on with another provider. I was incensed.

* * *

Today Hungary is often seen as a mysterious, landlocked, and homogeneous society of white Eastern European stock occupying a tiny stretch of land in central Europe, but it was not always this way. Like Canada and the US today, the Kingdom of Hungary was once the example of a cultural melting pot and home to Romanians, Serbs, Croats, Germans, Slovaks, Czechs, and other ethnic minorities. Hungarians were merely the majority. When most people think of World War I, it began with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo and ended with the defeat of Germany by the Allies[i]. The role and plight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire is often lost in the telling of World War I, but ask any Hungarian about it and they will tell you the story of the Treaty of Trianon.

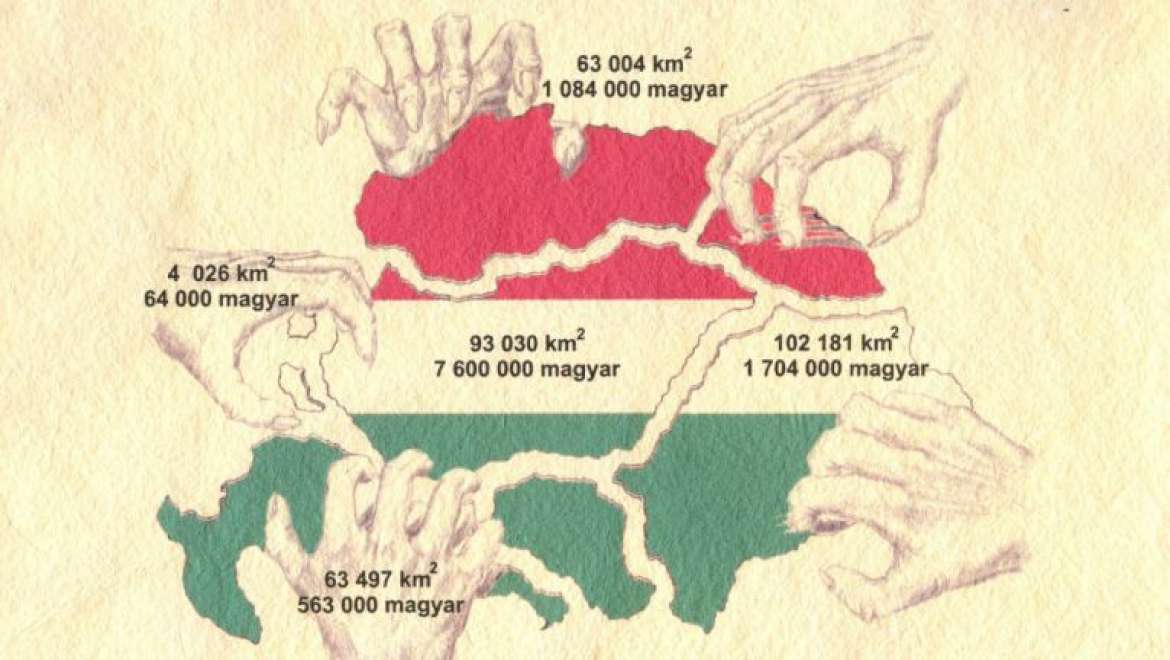

One of the explanations for the rise of Hitler is his fury over what he saw as an unjust disarmament and reparations, as Germany was forced by the victorious Allies to take responsibility for the atrocities of World War I. Little do most people know that the Kingdom of Hungary, now separated from Austria after the war, was also forced to disarm and pay reparations but, unlike Germany, The Kingdom of Hungary lost over half its territory and over half of its population with a few strokes of a pen. The main beneficiaries of these border changes were the countries right at Hungary’s doorstep and Hungarians now became the largest minority group in Romania, Slovakia, and Yugoslavia.[ii] Once one of the major political actors in the region between Western Europe, Russia and the Middle East, Hungary, and Hungarians, have been slowly and steadily choked out of existence over the last hundred years. The Hungarian language is part of the often disputed Finno-Ugric family and a map of the distribution and proliferation of Finno-Ugric speaking tribes will show you a nation of Hungarian speaking people surrounded by Latin, Germanic, and Slavic speaking peoples who all have far more in common linguistically with each other than they do with Hungary. In short, Hungary is a wholly unique language and culture whose identity and existence, whether real or perceived, has been perpetually under threat from its neighbours.

After my grandparents immigrated to Canada, Hungary was under the control of the Communist Party and it lasted for almost 40 years. In Canada, we would only hear whispers of what life was like in Hungary under the communists, but separating the facts from the various levels of propaganda was complex and out of my intellectual grasp when I was a teenager. Even as an adult, when I visited shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain, Hungary didn’t look all that different to what I was used to, or had experienced while travelling other parts of Europe, so being able to imagine life at that time never really took a form I could cling to. Now, with its shopping malls, international festivals, cell phones, and nightclubs, Hungary is completely modern and indistinguishable from most European countries and has been a member of the European Union since 2004. Hungary has made progress since shaking off the oppressive yoke of the communist era and seamlessly transitioned itself into the 21st century, all during the living memory of the people I get to spend quality time with when I visit.

My generation of first and second Hungarian cousins have started to have children of their own who never experienced life under the communists. And, although most of the family that may have experienced life in Hungary between the wars have mostly passed on, those that experienced life under the communists still have that experience etched in their memory. It is the kind of still simmering reality that when I ask my cousin, Márton, Magdi’s eldest son, what the political situation is like in Hungary these days he can casually respond with something like, “Well, no one is disappearing for speaking out against the government, so, overall, pretty good”.

In recent years, Hungary has begun to make international news again in the West. After its return to democracy in the nineties, the political situation remained rather silent to the outside world. Within Hungary, however, it was a turbulent time politically, punctuated by abrupt shifts in parliament with each majority party getting ousted during each political cycle. Although the last thirty years have been defined by Hungary’s integration into Europe and the world economy, the sentiment within Hungary, about Hungary, seemed to still be finding itself. That was the situation until 2010 when Viktor Orbán’s conservative Fidesz party won a majority in parliament and then won again in 2014 and 2018. In Europe, the Fidesz party won no friends mostly because of Hungary’s strong stance against immigration and leading to a European Union article 7 vote against Hungary who it was said posed a “systematic threat” to democracy. In Canadian news, images of Hungarians trampling swarms of fleeing immigrants and screaming at them to leave their country became the order of the day. The Hungarian government was labelled as authoritarian, its Prime Minister and its people as racists, and a nation acting as a fulcrum in the modern rise of populism that in turn led to the Brexit vote, other recent populist movements as in Poland, Donald Trump, and the rise of white nationalism in the US. Somehow all of these world events have become conflated with one another as all possessing the same anti-liberal seed that, if nurtured, poses that existential threat to democracy.

In present-day Canada, we are a nation of immigrants whose ancestors stole the land from the indigenous peoples who had been living there for centuries and developed it into the modern cultural melting pot that it is today. Five hundred years since the first Europeans set foot in America and First Nations have special rights – scant consolation for their indiscriminate extermination for five centuries. But we have moved on and it is something that we all accept. Were it not for Canada’s policies and welcoming attitudes towards immigrants and refugees, my own family would not have been able to bask in the freedom that we now enjoy. In my liberal bubble, immigration is good and positioning oneself as anti-immigration is abhorrent and lacking empathy for the plight of displaced peoples. The only points of view on the issue seem to rest at the poles and don’t allow for much nuance between them – such is the state of broken telephone that is that delicate triad of the media, politics, and people. There is a profound delusion that there exists a level of understanding between these three entities when each often acts against the others with its primary objective being nothing more than self-preservation. In Hungary’s case, the Fidesz party seeks to remain in power, the media has a responsibility to its shareholders, and the Hungarian people would like first and foremost for themselves and their children, and their children’s children, to remain Hungarian – the entente is delicate.

* * *

I stare out into the blurry landscape of open fields of sunflowers and tall grass speeding by as the train click-clacks along the track south from Budapest to Szeged where I am on my way to meet another branch of my extended family. I hear the syncopated beat of Latin rhythms emanating faintly from the earbuds of a young girl as she looks out the window and lip-synchs along with the song. Her fingers are delicately fidgeting a stylish choker necklace and, were it not for my obsessive concern over the status of my phone, the look of her would command a lot more of my attention. She reminds me of someone famous; she looks just like the girl in that movie; what was the name of that actress again? I can picture her so clearly in the film, but I just can’t put my finger on the name. My fingers instinctively descend toward my phone – it has all the answers. I unlock it and there is a reminder that I still do not have a signal, and without even saying a word to her I get to feel emasculated. It has been three days and no cell phone signal.

* * *

There were a lot of things about growing up in Montreal that simply funnelled my generation into having a liberal mentality, especially as it might concern immigration. By eight years old, and well into my teens, my soccer teams were made up of Anglophone and Francophone Canadians, kids of immigrant parents from Italy, Greece, Ghana, Honduras, Algeria, Egypt, Japan, Colombia, Mexico, Portugal, and Trinidad. Just about every country under the sun had some kind of representation. Although there was the occasional community club of Italians, they were not going to turn away a kid from Senegal who could score goals. Soccer teams in Montreal always looked like the United Nations, much like the best professional clubs do today – lest we forget that the Bosman ruling happened only as recently as 1995[iii]. Aside from the effects of colonialism and the frequent swelling and contracting of borders, European countries have for centuries been places that sent their peoples out, rather than bringing people in and the cultural mixing one sees in Europe is because of colonialism, not immigration. Whether we are willing to admit it or not, it is what visitors from the Americas like about Europe – we appreciate that Spain feels distinctly Spanish, that Italy is uniquely Italian, and that France is French – and it is why we spend our summers there visiting castles and museums and immersing ourselves in the local culture. The cosmopolitan nature of major cities seems to make them bleed into one another and today telling places like Madrid, Milan, Berlin, and Brussels apart is not as easy as it was 20 or 30 years ago. But, go out into the countryside and that is where European countries reveal their real character. It is also in these rural enclaves – “traditional” as visitors prefer to refer to them – that national and anti-immigrant sentiments tend to have the deepest roots. Nationalism has played a major role in shaping recent European history and was one of the major catalysts for two World Wars and the basis behind the Treaty of Trianon which dismantled the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hungary was once a major European power, but it was never a colonial power and there are no leftover traces of Hungarian merchants along the old spice road, no Hungarian diaspora, or tall tales of Hungarian pirates plundering the shores of the Caribbean. It has, however, been used over the last 60 years as a buffer state between the Western NATO allies and Russia, neither of whom have put the interests of Hungarians before their own. Hungary has become a pawn at the front of either end of the chessboard and its people expendable pieces between Russia and the West. Blaming Hungary for the current crumbling state of democracy and the rise of populism is akin to blaming climate change on cow farts.

The strides that Hungary has made to modernize cannot be understated. They are a nation that takes great joy in capitalism and not needing to apply, or bribe, for every modern convenience. But with democracy and capitalism came unemployment which reached as high as 12.3% in 1993. After declining during the turn of the century, unemployment rose again to over 12% until the Fidesz party took over and it has been on the decline ever since. Hovering now at about 3%, unemployment in Hungary is the lowest that it has ever been. The factors as to why the unemployment rate has fallen are numerous and complex but one major contributing factor is the Gypsy, or Roma, population. If Hungarians seem mysterious to the rest of the world, the Roma are even more misunderstood. On a good day, we think of the Roma as travelling free spirits and fortune-tellers who refuse to live by society’s rules that combine the beauty of Hugo’s Esmeralda with the sound of Django Reinhardt. On a bad day, we think of a marginalized segment of society that is unwilling to work, pay taxes, bathe, or contribute in any way to the society in which they live – the truth is somewhere in the middle. Under communist Hungary the Roma were able to take advantage of all of the social benefit programs and so, while many Hungarians toiled to help Hungary chug along through the latter half of the 20th century and make minimal gains, the Roma would make the same minimal gains without the toil. The resentment is real. When the Iron Curtain fell and many of the social benefits went away, large segments of the Hungarian Roma population immigrated to Canada under the pretext of seeking economic betterment. What they were seeking were social benefits like they had had in Hungary and it led to a wave of deportations of Hungarian Gypsies back to Hungary from Canada. One of the major reasons for that decline in unemployment is that the Roma population that remains in Hungary has been put to work. From some angles, it is viewed as a form of modern slavery but from others, instead of living off the state, they are rebuilding the state. They have become the class of day-labourers and construction workers and Hungary’s infrastructure has been the beneficiary. It has made Hungary a more appealing place for Hungarians to live and a more convenient place for foreigners to visit. However, the belief persists within the country that should more immigrants arrive, unemployment will rise, Hungary’s economy will decline, skilled Hungarians will emigrate elsewhere, and eventually the native Hungarian population will be outnumbered by an immigrant population. The story goes, if you are willing to work and be Canadian, then you are welcome. The same is true in Hungary. The big difference is that Hungarians believe that no one who isn’t already Hungarian really wants to be Hungarian which is the seed of their suspicion of immigrants. When someone immigrates to Canada they enter into one of the largest countries in the world, with one of the largest economies in the world, and an unblemished record of democracy since the country’s inception a little over 150 years ago. Immigrants are only asked to learn English (and/or French) – the lingua franca of the 21st century spoken by 1.5 billion people (1/5 of the world’s population) – and try to get a job and contribute to an economy with high social mobility. You would be hard-pressed to find someone keen to move to a country listed as the 54th largest economy by GDP and where they are asked to learn a language spoken by a paltry 13 million people. So why the problem and why this perception?

One problem that has plagued humanity for eternity is the idea that what works in one place will work everywhere – it is the “what’s good for the goose is good for the gander” syndrome. But nations do not live in a petri dish and every country’s challenges are unique to that country and have a solution that will only work in that country. People are fluid and what might be Hungary today might not be Hungary tomorrow. The Canadian border has held firm for over 150 years but any visit to Europe reminds us that borders rock and sway with the tide. Sometimes it is peaceful, too often it is at the muzzle of a gun. The European Union is one of the great successes of the modern era that has brought an unprecedented level of economic prosperity to the region and its member countries and Hungary has enjoyed these benefits. The European Union is a desirable place to live and immigrants and refugees seeking a better life look to it as a place where they can build a better life for themselves and better opportunities for their children. But the sentiment in Hungary is that immigrants and refugees are not coming to the European Union to remain in Hungary, but instead want to be in Germany. They believe that Hungary is being saddled with the responsibility of these immigrants seeking to reach Germany, and are being forced to provide them with the social benefits that the EU requires of them. Put another way, instead of the bully being cronies in Moscow, the cronies are now in Brussels. To a large number of Hungarians, it is Germany that pulls the strings and Hungary has to just accept it. It is not quite right, but it is not all wrong either and the seed of all the misunderstanding exists somewhere in that unholy triad of people, politicians and the media. The Hungarian language is so complex and difficult to learn that I have witnessed native speakers barely able to communicate without a conversation about flowers erupting into an argument, that I shudder to think what happens behind closed doors of committees of the European Union where Hungarian has to find a way to translate over to English, French, German, or Spanish. I have also never seen someone freak out and then actually calm down after someone reminds them to “take it easy”, so calling Hungary a threat to democracy seems like the wrong approach to me. Or at least it would if the point of the actions taken by the European Union were to have the Fidesz party change its policies. The truth is, the position taken by the European Union is to demonstrate to Hungary and the world that the interests of Hungary and Hungarians are subordinate to the interests of the Union – it is a way of putting Hungary in its place and using it as an example. It’s an easy card for Orban, as a politician, to play and, as one European Union member state prepares to leave (or not leave), has done little to slow the rise of populism.

* * *

After a couple of peaceful nights in Szeged, it was time for me to return to Budapest and get on with my journey. At some point during one of my walks with Kornél through the old city, my phone finally connected to the network and all of my nervous anxiety went away – my little world was back to normal. It was a brief stay in Hungary, but the phone card would be good in all of Europe so there was little to fret over at this point. The HÉV lazily made its way from Örs vezer tere to Mátyásföld as I tended to emails and news from around the world. I took a carefree walk around the neighbourhood to Magdi’s house where she was awaiting my arrival. We have a certain routine whenever I visit where we give each other space during the day but come together for a typical Hungarian supper of salads and bread and cold meats and cheeses. Magdi was curious to know what I had been up to since I had been away and invariably the story of my tribulations with the phone came up. I was loud and expressive in my storytelling and was sure not to leave out a single detail including the communication difficulties with the phone company, the apathy of customer support, and unrelenting consternation surrounding how this inconvenience might be affecting my business. By the time I was done, I felt like I had shared a tale that was sure to enrage anyone that heard it. My frustration with the bureaucratic barriers I faced along the way was so clear and evident that any listener would immediately feel a deep and profound sense of empathy for my ordeal.

Magdi giggled.

“You know what this makes me think of?” she said. “Back in the 1970s, we had a flat in Örs vezer tere in one of those big communist-style apartment buildings. You know, you’ve seen them when you take the train. Well, at that time we were able to get a telephone line because it came with the flat so that we could call our family members in the city or other parts of Hungary if they also had a telephone. But when we decided to move out to the old house in Mátyásföld we had to request to have a phone line put in. We had to wait for 18 years”.

[i] Of course the whole story is incredibly nuanced and complex. For brevity’s sake, the story often gets told this way to make way for the sequel which includes Hitler’s rise to power and justifications for crossing the Rhine and seizing control of Austria and the Sudetenland which preceded World War II.

[ii] Yugoslavia, with its seat of government in Serbia, itself eventually broke apart toward the end of the 20th century after the fall of Communism. Many parts of Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and northern Serbia were once part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

[iii] The Bosman ruling was a landmark case in professional European football for many reasons which I invite readers to investigate further for themselves. Here it is important only to know that, before the Bosman ruling, professional European football clubs were limited in the number of foreign players (this included players born in EU member countries) that they were allowed to field. So, for example, if you were an English club it meant that your club had to be comprised of a large majority of English players and was limited to a small number of players from other countries. The impact of this ruling reached its zenith when Internazionale of Milan won the UEFA Champions League, the most coveted prize in league football, in 2010 by beating Bayern Munich 2-0, where not a single member of Inter’s starting eleven hailed from Italy where the club was from. Marco Materazzi, who was born in Lecce, Italy, did eventually make it into the match in the 92nd minute. The final whistle blew to end the match about 90 seconds later without him ever touching the ball.