Third Dose

The Ecuadoran Regional Highway 59 rolled down the mountain trading waterfalls and jungle palms for a dark, cloud-covered, swamp leading to the coast. The town of Huaquillas was a disordered jumble of streets and merchants crowding the road to the bridge where Ecuador becomes Peru. The highway traverses a more formal border crossing manned by officials and armed guards.

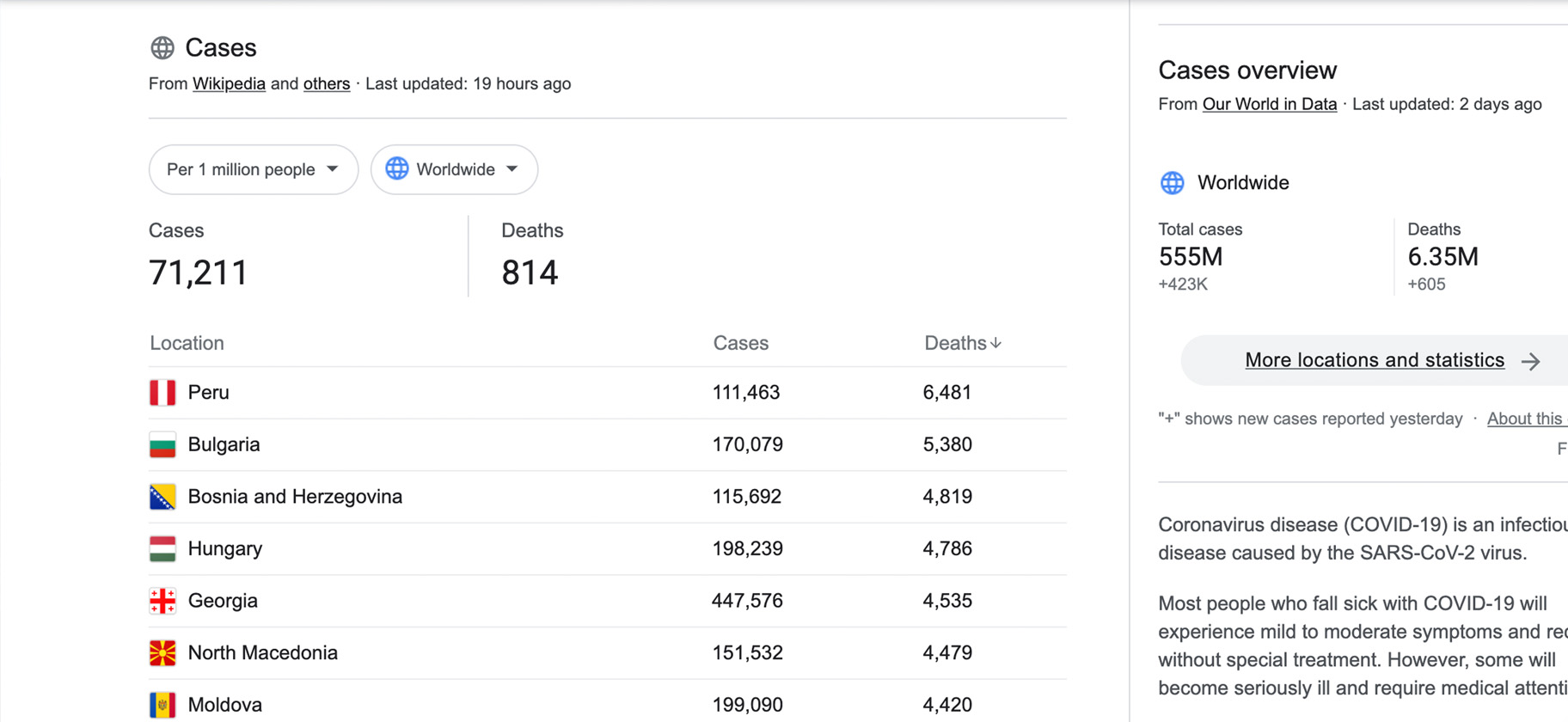

Vaccine campaigns and the spread of the omicron variant were leading to the easing of travel restrictions around the world. During the pandemic, which had now dragged on over a year and a half, at the time no country had endured more deaths per capita than Peru. What factors contributed to such poor outcomes were multifarious and debatable but it was clear that the Peruvian people had suffered greatly and it had taken its toll on the country’s psyche.

The rumour was that Peru was the one country in South America that required proof of three doses of vaccines in order to gain entry. Where we came from, and for most countries, two doses sufficed. We had left our respective countries before third doses were recommended, or even available, having been reassured that one shot of mRNA vaccine plus a booster was considered full immunization. When we arrived at the border, we were denied entry for not being able to provide proof of having had a third dose. My explanation that we were fully immunized by the laws of our own country did not persuade the agent at the border responsible for issuing health passes. As proof to us of the arbitrary nature of the circulating health protocols and policies, we were told to simply visit a nearby tent and get another shot and they would let us enter. There was no consideration given for the date of our last vaccine or the fact that their own policies on the health declaration forms we were required to fill out indicated that persons could only enter two weeks from their last vaccine. The message was simple, succumb to the shot and gain admittance.

Peru and its bureaucracy looked dark sitting under a thick and dreary cover of cloud. According to their own literature, visitors could enter with just two doses and a negative PCR test issued within the last 72 hours. We returned to Huaquillas and found a laboratory that conducted rapid antigen tests with results in 20 minutes for about $30 each. Having travelled extensively during the pandemic, I had endured my share of nasal swabs. Jenia, on the other hand, had rode out the pandemic from Bali and had up to then avoided the probe. She was not an easy patient bobbing and weaving as the nurse struggled to insert the swab. Eventually, I had to enter the room and hold her hand to comfort her and allow the nurse to retrieve a meaningful sample.

With our certificates in hand, we returned to the border crossing and were, once again, denied entrance. Jenia had often criticized me for surrendering too easily to the often irrational demands of others. In my youth, I was happy to fight for the things that I thought were right believing I could fashion a compelling argument that would bend the minds of others to my will but, in midlife, I was now keen to avoid conflict. When I suddenly balked and not being allowed to enter and, raging with testosterone, made a point of standing up for us, Jenia grabbed me by the arm swelling with her own hormones and with admiration for my sudden assertiveness.

We had travelled all the way from Cartagena and I had not come this far to only come this far. I could not ask Jenia to get the shot. She had her own views on the matter and I was not about to leave her standing at the border. My only recourse was to attempt to reasonably duke it out with this faceless, nameless, roadblock that stood between me and my own plans. I have found that it is easier for border officials to just say yes. If a visitor is attempting to enter in good faith and with all of the proper legal documents, in order for the official to refuse entry they would have to create a well-supported case.

The point of issue was that we had come with rapid antigen tests and not 48-hour PCR lab results. Rough and rugged with every manner of persecuted individual passing through, Huaquillas is not the kind of place that one wants to spend any longer than one needs. Returning was out of the question – it was entry into Peru or bust. My Spanish grew in confidence as I vehemently flashed the various documents supporting our claim. I pointed out the sections in their own covid policy available on various government websites that indicated that a 48-hour PCR lab test was only required for those wishing to enter who had not completed their two-dose vaccine schedule and that the combination of a complete schedule accompanied with a rapid antigen test was sufficient.

The official in charge of issuing health passes and I were now engaged in a standoff. I looked them gravely in the eye while I calculated what I would do if they persisted in barring the way. They looked at me probably curious what I might do, or what I was capable of, if I was pressed too far. The truth was that, though convinced that I was right, I was out of ideas. If this did not work, we were sunk and would be forced to return to Huaquillas and try it all again on another day hoping for someone a little less rigid to review all of our documents.

After pondering the consequence of our admittance, with reluctance, the official filled out our health passes and we were allowed to proceed to immigration. The health passes we were given were nothing more than small slips of stamped paper that were required to present to the immigration officers in charge of entering our documents into their database. Paperwork, or any manner of health declaration for statistical purposes, was non-existent. What the Peruvian government might have done with this information one can only speculate. Like with every health measure I had seen since the emergence of this horrible plague that had enslaved us for far too long, dictums issued at the Peruvian border felt strictly performative. If statistics are to be trusted, the Peruvian people suffered more than most around the world. Like the proverbial chicken and egg, one wonders if the intensified scrutiny and barriers to entrance were a response to, or a cause of, such poor outcomes. In the face of this pandemic, I had had my own dreams and ideals described as illogical but, to me at least, it was clear that they were simply coming up against strategies that were equally illogical. I have long held the belief that there is no one at the helm. Everyone is their own expert until a single anomaly bares its teeth. I find it better to be respectful of the fact that none of us really know what we are doing.