Tranquilo

I met Rafa back in 2009. I was walking with a limp recovering from a broken leg and my life was a complete mess. I had been out of work for almost a year and was scrambling to fill the spare room in the apartment I had leased with a roommate that I could tolerate and who, above all, could tolerate me. I enrolled in one of Montreal’s recording arts colleges which allowed me to take out a student loan and helped me to cover some expenses for the next year as well as use some of that capital to invest in recording equipment and software. Without a job and little to do, I was working on writing and recording songs as a hobbyist in my spare time, so I figured I should learn how to be at least be good at it. I still worked odd jobs to make ends meet fitting them into my schedule where I could. I worked at a call centre running marketing surveys, I wrote small articles for local news where I could get a scoop or pump out an advertorial for a few bucks, and I even worked as a soldering technician for a glow-in-the-dark products company where I designed women’s lingerie with LED lights.

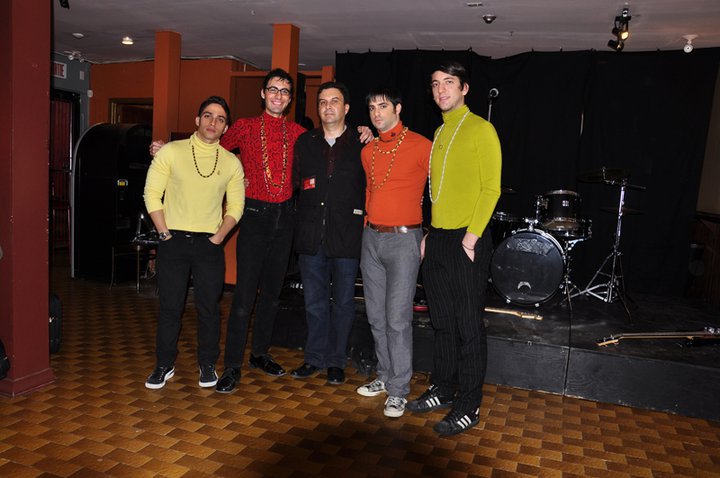

At recording arts college is where I met Jorge. At age 30, I was the old man of the class; at age 20, Jorge was the baby. Jorge was tall and lanky with long hair – a happy-go-lucky gay kid who barely fit into his body. He could stretch his spindly fingers the length of a guitar neck and had the most natural ear for music of anyone I ever met. Dubstep was the emerging trend back then and recording arts colleges attract their share of metal heads and guitar junkies obsessed with their amps but, as a singer-songwriter, I was looking for a band to play indie rock. Jorge loved classical music and jazz and, if you gave him just a few minutes, could play any instrument you handed him. Born in Mexico, Jorge connected himself with the Latino community in Montreal and introduced me to Jose Maria and Rafa – a guitar and drum duo from Colombia. The three of them had been jamming on old Mexican and Colombian rock standards for a few months but they were looking for a project that they could get behind and so they brought me in and started jamming on some of my songs.

For a couple of years, we formed a unit and played shows in cafés and at festivals around Montreal. We played a mix of Mexican rock songs by bands like Molotov, Café Tacvba and Maná, as well as our own songs translated from English into Spanish because we were attracting a Spanish-speaking audience.  We even put our recording lessons to use when we were brought on to appear and perform as the band in a low-budget Mexican production of a love story set in the 1960’s that was filmed in Montreal. We were a small time outfit and struggled to find shows to play and to identify just what kind of band we were, but there was an energy when we got into the jam room. At the start, the jam room was Rafa’s apartment which was down the block from the college. On most weekends, with a couple of small amps and Rafa on the kit, we sang in the room without microphones for the droves of Colombians and Mexicans and friends of friends that came traipsing through his apartment. We would stay up late and drink beer and jam until midnight or whenever the neighbours started to complain and then we would head out to a party with the acoustic guitars and sing at someone else’s house nearby. Eventually, we were pumping out enough noise that Rafa was threatened with being evicted which meant we needed to move our rehearsals to Jorge’s parent’s basement in St. Laurent. Getting out to that area of town was a process and, if rehearsal time was agreed upon at 3 pm, we would not start until past 6 pm which was about when everybody needed to head home.

We even put our recording lessons to use when we were brought on to appear and perform as the band in a low-budget Mexican production of a love story set in the 1960’s that was filmed in Montreal. We were a small time outfit and struggled to find shows to play and to identify just what kind of band we were, but there was an energy when we got into the jam room. At the start, the jam room was Rafa’s apartment which was down the block from the college. On most weekends, with a couple of small amps and Rafa on the kit, we sang in the room without microphones for the droves of Colombians and Mexicans and friends of friends that came traipsing through his apartment. We would stay up late and drink beer and jam until midnight or whenever the neighbours started to complain and then we would head out to a party with the acoustic guitars and sing at someone else’s house nearby. Eventually, we were pumping out enough noise that Rafa was threatened with being evicted which meant we needed to move our rehearsals to Jorge’s parent’s basement in St. Laurent. Getting out to that area of town was a process and, if rehearsal time was agreed upon at 3 pm, we would not start until past 6 pm which was about when everybody needed to head home.

Jorge went on to University and got himself a fine arts degree in music. Over the years, he has worked with a number of musical projects from church choirs to rock bands and has worked as a session musician for a number of Montreal artists. Jose Maria, way back when I met him was dating a Mexican girl named Marifer. He went on to one of Montreal’s musical conservatories to specialize in classical guitar. When Marifer suddenly became pregnant they got married. Jose Maria eventually transitioned from music and returned to university to study physical sciences and mathematics. They are still a happy family and still live in Montreal. Rafa went on to work as an engineer for a couple of companies in Montreal. Drummers are all womanizers and Rafa was no exception. When I met him, he was dating a girl named Sofi who he proclaimed was the woman of his dreams and who he would marry one day. When we were all jamming together, he was not the faithful doting husband that he would become, but he did eventually devote himself fully to the project of raising a family and married Sofi, as he promised he would, in 2015. Family life meant returning to Colombia. Rafa and Sofi spent some time, early in their marriage, separated, she in their hometown of Cartagena and Rafa working in Medellin. The pandemic helped Rafa relocate to Cartagena on a permanent basis and, by the time I dropped in, Sofi had just given birth to their second child while Rafa was integrating himself into a new job working for a pharmaceutical company.

Seventeen years earlier I had come to a hard stop in Panama. I was out of money. Even if I had money there was no more road. To this day, the asphalt comes to a dead-end in a small village by the Darien Gap that separates Panama from Colombia. Back then my curiosity got the better of me and I inquired how passengers continued the route. Informants in the area advised me that, for a price, cars could be loaded onto ships passing through the canal headed to the port in Cartagena. Since that day, Cartagena has always been the launching point of a quest born in the Belmont way back in 2005, and now the day had come.

Even before arriving in Colombia, I reached out to Rafa and informed him of my intention to drive the length of the continent. Exchanging text messages I expressed, above all, that I would need his help to purchase a vehicle. A decade had passed since we had last seen each other so it was essential that we caught up and got to know each other again before getting serious about buying a car. I told Rafa that I was giving myself a month to achieve this goal, so there was no real rush. He responded with a photo of a small turtle being gently patted on the head with the word “tranquilo” emblazoned on the bottom.

Back in college, Rafa was the bad influence that I needed to get me out of my shell. He was the one feeding my self-confidence to get me to sing and win the hearts of the girls he would later sleep with. He devoted one of his toms to holding his beer and a vuvuzela was always on hand at his parties for funnelling two beers in a breath. He rarely missed an opportunity to demonstrate how to accomplish this feat. Ten years later, getting a hold of Rafa was tricky since his new job, combined with parenting responsibilities, kept him occupied every moment of the day.  When the weekend came, he invited me to see his home in Bocagrande and the first thing he did was offer me a beer – an indulgence I had not sated in months. We took a taxi into the old city where the first thing we did was visit one of Rafa’s favourite rooftop bars where he ordered a beer. We walked through the streets of the old city and Rafa bought a beer from a shop to drink along the way. We stopped to get out of the heat and passed some time talking about life at one of Rafa’s favourite bars where he bought himself another beer. After he polished off a second beer, we headed out to explore more of the city before stopping at another bar for a beer. After the sunset, we stopped in at a popular local restaurant in the Getsemani district and Rafa polished off a bottle of wine. It was about this time that I pointed out to Rafa just how much alcohol he had imbibed.

When the weekend came, he invited me to see his home in Bocagrande and the first thing he did was offer me a beer – an indulgence I had not sated in months. We took a taxi into the old city where the first thing we did was visit one of Rafa’s favourite rooftop bars where he ordered a beer. We walked through the streets of the old city and Rafa bought a beer from a shop to drink along the way. We stopped to get out of the heat and passed some time talking about life at one of Rafa’s favourite bars where he bought himself another beer. After he polished off a second beer, we headed out to explore more of the city before stopping at another bar for a beer. After the sunset, we stopped in at a popular local restaurant in the Getsemani district and Rafa polished off a bottle of wine. It was about this time that I pointed out to Rafa just how much alcohol he had imbibed.

Yeah, yeah, he replied. I’m just taking it easy today.

You’re not drunk? I asked.

Ah, maybe a little, he replied. Gotta keep my tolerance up since I don’t touch alcohol at all during the week.

He seemed lucid enough and as we left the restaurant to close the evening and head back to Bocagrande, I brought up what I was looking for in a car. Rafa turned me onto a couple of auto trading websites that I could explore and also casually mentioned that it was about time his father sold his car.

I had been in Cartagena a week and there was still lots of time. I casually perused the auto trading websites and showed a few options in my price range to Rafa. Buying a used car in Colombia comes with its slate of warnings and bureaucratic hurdles. Added to this is the extensive list of specific considerations to account for before buying, such as: how many owners the car has had; is its license plate up to date; what is the status of its SOAT; and, if it is older than 8 years, has it passed its performance inspection? There is no official agency directing traffic on these websites and every automobile’s legitimacy ranges from buying from an authorized dealer to a car that may have been stolen.

Rafa’s main concern was power since most cars in my price range were compact. It would be one thing if you were just driving around Cartagena, he told me, but you plan to drive through the Andes. I’ve seen some of these small cars that can’t make it up a ramp in a parking garage. And you’re going to have all of your bags in the trunk.

Rafa gave me the names of a few models that were popular in Colombia but were also likely to be available in most of South America. You want to make sure that you are driving a car that is a manual transmission, he advised. That way, if there’s a problem you know that they will be able to find any parts and repair the car easily.

All of this advice helped me refine my search and hone in on a few key details but my options were few in Cartagena with better options in nearby Barranquilla. As the weeks passed, I began sending links of used cars to Rafa more frequently. I would wait with bated breath for his response hoping he would definitively say that the car that I found was ideal. But each time he would respond with hesitation and concoct some reason to be suspicious. Rafa feared reliability more than anything else. He would talk at length about the various problems that Colombian drivers become accustomed to and he was keen to keep me away from mechanics since Colombians were distrustful and believed only in those that had been servicing their cars for their entire lives. The fable of the mechanic living long and large on the constant flow of funds from those that knew no better, and especially getting the better of a gringo, was famous throughout the country. Because you don’t speak much Spanish, Rafa would say, they are going to think they can take everything from you.

There were a couple of ways to approach the problem. One was to spend more money and invest in a car that was newer and in better condition and also more likely to get me to where I wanted to go with the hope of reselling it at the end. Or, there was the option of buying something dirt cheap while half expecting it to give me problems, run it to the ground, and lead to me more than likely declaring it a loss by the end of the trip. I found a couple of old Volkswagen Beetles for sale in Barranquilla where the owner was asking as low as about $2500. The idea of riding through South America in an old VW Beetle had a certain appeal regardless of the price tag. I know it sounds good, Rafa advised, but it’s unrealistic. Also standing in my way was the fact that my Spanish was limited and keeping the transfer of the vehicle above board and legal was going to present a challenge.

As the month was drawing to a close, I brought it up to Rafa that he had mentioned his father’s desire to sell his car. This would have eased one anxiety for me – that the car’s previous owner was at least trustworthy. Moreover, if they were selling it, they would be as inclined to keep everything above board and legal as I. Rafa confirmed that it was a possibility and that he would speak with his father. A few days later they came around to my apartment in Bocagrande so that I could test it.

I wanted to love it. I hoped that I would get inside, take it for a spin, and that it would run smooth with all the bells and whistles and that Rafa’s father would get sentimental about who he was selling it to that he would just give it away for a song. I released the clutch too quickly and stalled the car. When I stepped on the clutch to start the engine, it would not turn over. Rafa’s father demonstrated a trick to tap the clutch, turn the key two clicks, push the clutch, and then start the ignition. It took a few attempts, but I got her going. I took it for a test around a few city blocks in Bocagrande just to see how it rolled. The car was a burgundy-coloured 2011 Renault Scala and was the most plain-looking sedan you had ever seen. It was in fair condition and had not accumulated an absurd amount of kilometres. The salt in the air around Cartagena clings to everything and the bottom of the car was showing signs of rust. The motor sounded good and, if anything, it not being much to look at meant that it was unlikely to draw attention from the would-be thieves that might be lurking through South America. We talked about my budget and, in that regard, Rafa’s father’s car, which he was willing to let go for 22.5 million pesos, fit right in my wheelhouse. Rafa reassured me that it was a strong car that could make the trip and that his father had taken good care of it over the years. With their family being on the other end of the sale they would also help me navigate all of the bureaucratic hurdles and all of the paperwork. In speaking together, I developed a sense that they had just as much interest in seeing me achieve my goals as I did. Listen, Rafa reminded me, the car is in good condition, but I can’t guarantee nothing will go wrong. My father will get the car looked at by his mechanic. The back tires need changing and he says that he will take care of that. But the car is good. I mean, it should be good. It would be a risk no matter what car you buy. And I know these kinds of guys that have these cars like the ones you were showing me and I just don’t trust them. My father takes good care of his car. I can’t guarantee nothing will go wrong with the car. I mean, I hope nothing will.

I wanted to love it. I hoped that I would get inside, take it for a spin, and that it would run smooth with all the bells and whistles and that Rafa’s father would get sentimental about who he was selling it to that he would just give it away for a song. I released the clutch too quickly and stalled the car. When I stepped on the clutch to start the engine, it would not turn over. Rafa’s father demonstrated a trick to tap the clutch, turn the key two clicks, push the clutch, and then start the ignition. It took a few attempts, but I got her going. I took it for a test around a few city blocks in Bocagrande just to see how it rolled. The car was a burgundy-coloured 2011 Renault Scala and was the most plain-looking sedan you had ever seen. It was in fair condition and had not accumulated an absurd amount of kilometres. The salt in the air around Cartagena clings to everything and the bottom of the car was showing signs of rust. The motor sounded good and, if anything, it not being much to look at meant that it was unlikely to draw attention from the would-be thieves that might be lurking through South America. We talked about my budget and, in that regard, Rafa’s father’s car, which he was willing to let go for 22.5 million pesos, fit right in my wheelhouse. Rafa reassured me that it was a strong car that could make the trip and that his father had taken good care of it over the years. With their family being on the other end of the sale they would also help me navigate all of the bureaucratic hurdles and all of the paperwork. In speaking together, I developed a sense that they had just as much interest in seeing me achieve my goals as I did. Listen, Rafa reminded me, the car is in good condition, but I can’t guarantee nothing will go wrong. My father will get the car looked at by his mechanic. The back tires need changing and he says that he will take care of that. But the car is good. I mean, it should be good. It would be a risk no matter what car you buy. And I know these kinds of guys that have these cars like the ones you were showing me and I just don’t trust them. My father takes good care of his car. I can’t guarantee nothing will go wrong with the car. I mean, I hope nothing will.

The pandemic destabilized the used car market. There was a short supply and they were in high demand which drove up prices. I could have stayed in Cartagena for a year and never run into my dream car. Sometimes good enough is good enough. The fact that Rafa’s family needed to be involved in the process eliminated one huge source of anxiety which was how to actually get the sale done legally. We agreed in principle and, soon after, Rafa’s family enlisted the aid of someone they knew with connections within the Colombian department of transport and motor vehicles to help us through the process. Rafa’s brother came to where I was staying with forms to fill out and to collect money to pay the broker. The next day we visited a notary to pay a small fee and stamp some papers declaring that both parties had agreed upon the sale. All that was left was to have the title of the car transferred over into my name and for me to actually pay Rafa’s parents.

Because I was not Colombian, in order for the sale of the car to be legal I needed to have my information registered with the Colombian Minister of Transport. Once registered, then all of the forms and documents related to the sale would need to be verified with the department so that the car could be legally transferred over to me. In order to do this, we needed to visit the Secretaria de Transito in nearby Turbaco where we would meet with the broker who would then grease the wheels.

I set my alarm for 5 am and waited by the window of my hotel for Rafa’s father who was on his way to collect me and take us to the office. I waited for two hours before growing impatient and reaching out to Rafa. He’s on his way, I was reassured. I got a taste of Colombian driving as we headed out of town and up into the hills toward Turbaco. When we arrived at the office, a large, official, government building, we were told we had gone to the wrong place and that the broker that we were supposed to meet would be at another office closer to Cartagena. The Secretaria de Transito was nothing but a small glass door located on the side of a Petromil Station. There was a lineup down the block, but we had our broker. Rafa’s father asked the security guard at the door for information and then started making calls. He reassured me that the broker was on her way.

My Spanish is rudimentary and Rafa’s father spoke no English but we managed to understand each other using a combination of basic Spanish and hand gestures and smiles. When I woke that morning, I had expected to be at the office when it opened at 7 am and by now it was well passed 9. After an hour of waiting for the broker, she eventually arrived and strode in like she owned the place. She went over to the security guard at the door and I told myself that this is where the money and the connections were going to pay dividends. After a minute, she stepped back from the door and spoke with Rafa’s father and sighed whispering, Tranquilo.

People waiting in the queue continued to pass in and out one at a time while we waited. I had surrendered control of the situation to Rafa’s father and the broker, but with the lack of sleep, the noon sun rising and the heat climbing into the thirties, my hands were shaking and I was growing impatient. Tranquilo, they said to reassure me. To calm my nerves a little, Rafa’s father treated me to a coffee and buñuelos. After another hour of waiting, the security guard called us over and the broker and I were let into the building while Rafa’s father waited outside. Before meeting with an agent, we were told to sit down and we were handed a chit, a loose scrap of paper, with a number written on it and told to wait until we were called. The broker and I waited a further hour.

An agent reviewed my documents, reviewed the notarized forms, reviewed the documents relating to the vehicle, and took my fingerprints. I paid a small fee and then we headed back to Cartagena. Rafa’s father invited me up to their apartment in Manga for a refreshment and then I drove my car to my hotel. I was now the owner of a burgundy-coloured 2011 Renault Scala that was getting set to take its first steps across the whole of the continent.

There was enough trust that I took possession of the car and I still had not transferred a cent over to Rafa’s parents. I had the money, but transferring that amount was going to take some strategy. Eager to avoid large fees, I made a couple of bank transfers as well as maxed out transfers through a money-transfer brokering site called WorldRemit. Though I had their blessing, it felt wrong to leave Cartagena without being assured that a portion of the debt I owed had been paid. We got held up in Cartagena for a few more days figuring out how to complete the various transfers of funds. Once 80% of the money had been successfully transferred we set out on the road toward our first destination – Barranquilla.

Between all of the red tape and the uncertainty, buying a decent car at a fair price in Colombia was a far more difficult endeavour than I had anticipated. As I would learn, nothing moves swiftly in Colombia. You might have your own objectives, but you can be certain to be met with adversity. The road ahead may seem clear but for someone in a position of authority requiring their slice barring the way and reminding you, Tranquilo. In the twenty-first century, you are not going anywhere unless someone says it is okay, so be patient.

By the time I was leaving Cartagena, the month I had anticipated came and went. When Rafa and I first spoke, he was full of suggestions of things to see and do and the potential of us coordinating plans none of which materialized. We met socially only one other time during my six weeks in Cartagena, but I did get my car and am forever grateful for the role he played in that. My entry visa was set to expire in another 6 weeks which meant I couldn’t dawdle through the country toward Ecuador but even then six weeks seemed like plenty of time. Tranquilo, I told myself. I looked at the car upon which I would rely for the next many months until I had driven her as far as she could go and her name became clear. Patience is required in Colombia because nothing moves swiftly, but there is always time. If the goal is the only focus then one cannot cherish the steps along the way. With too many steps still to count, I now had a way to make them all if her heart was strong. One at a time. Tranquilo.