Travel in the Age of CoVid-19

I was staring up at the big board as beads of sweat formed on my brow. It could have been the 32-degree heat in Bali, or it could have been the fact that I was tracking the uncertain status of a flight called JQ116. But deep inside I was worried that it could have been the beginnings of a fever that would have prevented me from entering the terminal. It had to be today. I had to leave. There was no more putting this off.

Tensions were high and customer service lines were long because of the number of people trying to leave the country and unable to board flights to their various destinations. A young man in a Michael Jordan basketball uniform approached me and through his thick French accent asked which flight I was supposed to be on and if I knew of any cities that still allowed transit passengers. I informed him that JQ116 was heading to Singapore, but that it was the last flight out as the airline was suspending operations and the Singapore government had recently put out a notice that they would be barring all travellers, even transit passengers, from entering the country as of midnight tomorrow. He was trying to get home to France but with so many airlines no longer offering services, so many flights being cancelled, and so many airports shut down, he was unsure of any route that could actually get him to where he needed to go. It was already the late afternoon and I had not slept a wink after a night of researching and strategizing how I was going to get back to Canada. I knew, if they even let me board my flight, that the next 36 hours were going to be filled with uncertainty and would be equally sleepless as the night before. But by now I had done the research.

“Look into Emirates,” I told him. “I’ve heard rumours that they still fly to Europe.”

He asked me where they fly from.

“Dubai, I think, but go on their website and check to make sure,” I told him. “Find a flight and pray.”

He wanted to know if Emirates would fly specifically to France.

“Does it matter?” I asked.

* * *

Seven weeks earlier, I had arrived in Bangkok still with lingering symptoms of an illness I had picked up in Nepal. I was concerned that I would not be fit enough to fly after spending a full twenty-four hours plastered to my hotel bed and having lost a few litres of water weight. It was the second illness in just a matter of weeks and, though I was feeling well again, having travelled through some areas of the world that are considered high-risk for all kinds of infectious diseases, I decided to have blood and fecal tests.

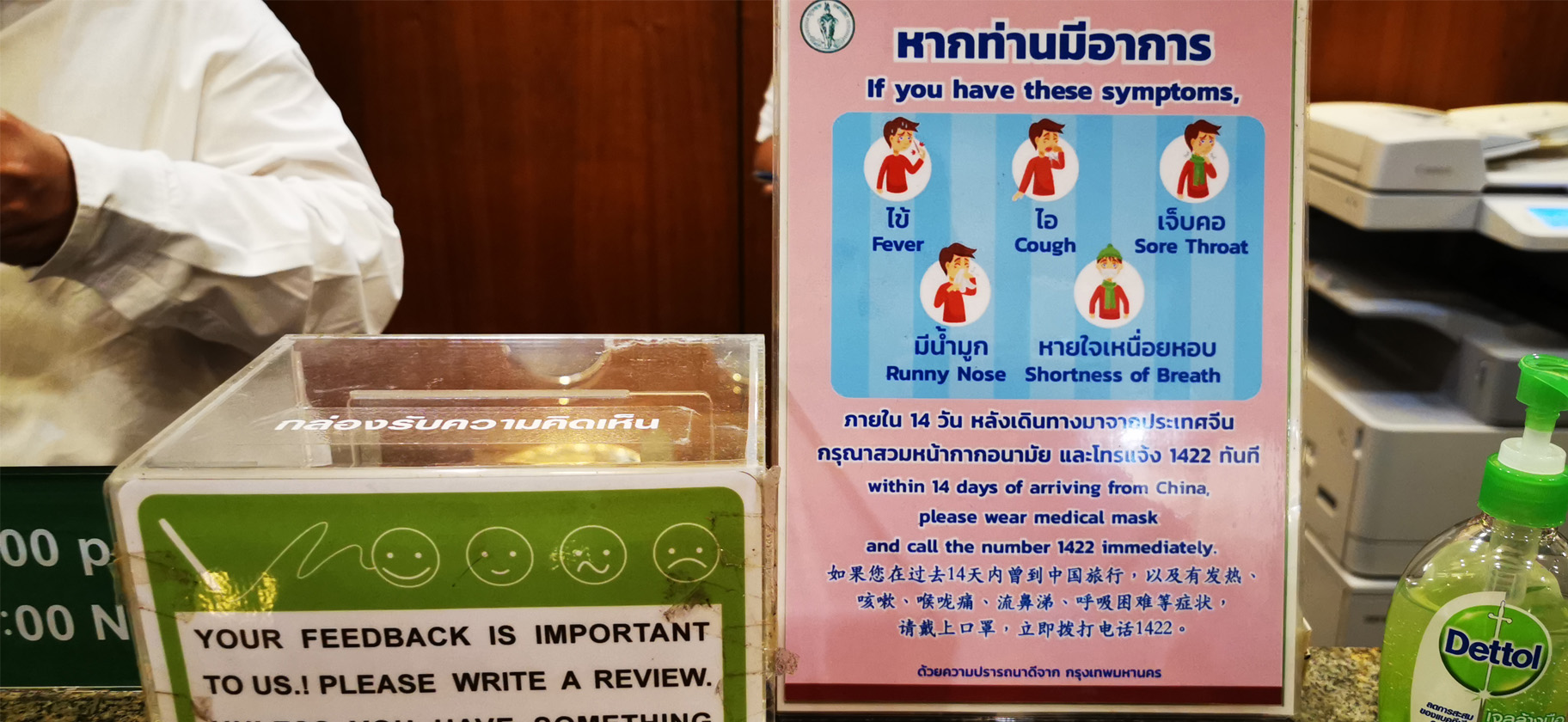

While registering myself as a patient, I was approached by a man in a mask who pointed a pistol-like wand at my forehead to take my temperature. I had been offered a mask before leaving my hotel earlier that day but declined, but at the hospital, I was handed a mask and ordered to wear it. Before filling out my information I was asked by the administrative assistant if I had recently travelled to China and if I was experiencing any respiratory discomfort.  There were warning signs up in the hospital advising patients to wear a mask if they had been having flu-like symptoms within 14 days of having visited China. There had been whispers in the media of an outbreak of a new disease that had already infected more than 10,000 people with its epicentre in Wuhan, in the Hubei province of China. An airborne illness leading to flu-like symptoms that was potentially fatal had begun its journey around the world now having reached Europe, the United States and Canada, and several southeast Asian countries including Thailand who, with 19 confirmed cases, was leading the way in terms of cases outside of China. The disease had already killed around 250 people in China and it was believed that it was now spreading within the local population in Thailand as well. I finished a round of antibiotics I purchased in Nepal and, when the tests came up negative, went about my business – the problems in Wuhan still seemed very far away.

There were warning signs up in the hospital advising patients to wear a mask if they had been having flu-like symptoms within 14 days of having visited China. There had been whispers in the media of an outbreak of a new disease that had already infected more than 10,000 people with its epicentre in Wuhan, in the Hubei province of China. An airborne illness leading to flu-like symptoms that was potentially fatal had begun its journey around the world now having reached Europe, the United States and Canada, and several southeast Asian countries including Thailand who, with 19 confirmed cases, was leading the way in terms of cases outside of China. The disease had already killed around 250 people in China and it was believed that it was now spreading within the local population in Thailand as well. I finished a round of antibiotics I purchased in Nepal and, when the tests came up negative, went about my business – the problems in Wuhan still seemed very far away.

A week later, I arrived in Hanoi. At immigration, I was asked to fill out a health declaration card. On it were tick boxes where I had to state whether or not I had recently been to Hubei province in China or if I had recently been suffering from any respiratory symptoms. I had been waylaid at the airport in Bangkok and did not arrive until late at night so I had a car from the hotel where I was staying pick me up from the airport and the driver handed me a mask to wear during the ride into the city. He didn’t speak English so he could not explain to me why he was handing me the mask and, rather than make a fuss, I politely obliged. I had heard rumours of Hanoi’s poor air quality and figured that his handing me the mask was a precaution for me not to breathe in too much of the local air. Upon arrival at the hotel, at check-in I was asked to fill out another health declaration card stating that I had not recently travelled to Hubei province in China, nor was I recently suffering from any respiratory symptoms. This now began to pique my curiosity. Something clearly had the people of Vietnam on high alert. I would later learn that there were 10 reported cases in Vietnam of the virus from China which still did not have a name and was being referred to in news segments as a “novel coronavirus”. Internet memes relating the virus to the Mexican beer company began to circulate a day later. At the same time, the US was reporting 12 cases but it was business as usual.

From Hanoi, I travelled to Ha Long Bay, one of the most touristed areas of north Vietnam. It had become a ghost town. In Ha Long there is a theme park called Sun World – their version of Disney Land – that was completely shut down. Hotels were nearly empty and sightseeing tours of the bay had cut their rates as a way to attract the last few tourists. Travelling back into port from the bay, I laid out on the deck of the boat to feel the wind off the sea and breathe the air. Tony, the boat’s tour guide, was swiping through news reports on his phone and told us that the nearby Cat Ba Island had been closed off to anyone carrying a passport from a country that had reported even a single case of the coronavirus. Canada, with 7 cases at the time was on that list. News reports were beginning to circulate of a cruise ship in waters off the coast of Japan that was leading the way in cases outside of China, and with it came the jokes circulating on the nightly talk shows about the high likelihood of contracting any illness on a cruise.

As I began to travel south through Vietnam, reports came out of health officials in the country responding to a small cluster of cases in the Son Loi district on the fringes of Hanoi and completely locking down the area. At the time, the entire country of Vietnam was reporting only 16 cases, but schools around the country were shutting down to help contain its spread. At the same time, the United States had only 15 cases and the Diamond Princess cruise ship had as many cases on board as all the other infected countries, outside of China, combined. For myself, the US and North America, and Europe everything was still humming along, but for certain targeted areas of Vietnam, it felt like the attitude was: it’s time to pull up the bootstraps and beat this virus before it beats us.

Travelling through Vietnam was an incredible adventure where I swam daily in the ocean, ate fresh tropical fruits, rode around on a motorcycle to the fringes of the towns and cities while sampling every variety of noodle soup at street stalls along the way. For the 30 days of my visit, until my visa expired, Vietnam was a traveller’s wonderland. From February 14th to the 6th of March when I finally left, Vietnam reported zero new cases of coronavirus infections. When I left Vietnam, life still felt somewhat normal. The number of confirmed cases in China had skyrocketed to 80,000 with just over 3000 deaths. A new cluster of the virus had sprung up in South Korea, who were in the midst of a widespread testing campaign to curb the over 6,000 cases and 50 deaths that had sprung up there before things got out of hand. Iran, which had suffered over 3,000 cases and more than 100 deaths, became another cluster and began to have travel restrictions imposed on it at airports around the world. In the week before I left Vietnam, its imminent arrival across the Pacific was getting attention in North America but was still being pooh-poohed in the media as being no more of a concern than the seasonal flu. It took an unusual cluster in Italy where they were approaching 4,000 cases and almost 150 deaths that seemed to spark the attention of the entire world.

When I landed in Singapore I was once again asked to fill out a health declaration card. Before going through immigration there was a man with the pistol-like wand taking my temperature and asking all the passengers if they had recently been to China, but now adding Iran and Northern Italy to that list. In Singapore, I spent six days visiting friends and hearing news reports from back home about people stockpiling food, hoarding toilet paper and fights breaking out in liquor stores over bottles of wine. The NBA season was postponed, and the NHL was considering postponing their season as well. European football matches were beginning to take place behind closed doors. Signs were up around the city reminding people to wash their hands, but the malls and the hawkers in Singapore were still operating.

When I landed in Singapore I was once again asked to fill out a health declaration card. Before going through immigration there was a man with the pistol-like wand taking my temperature and asking all the passengers if they had recently been to China, but now adding Iran and Northern Italy to that list. In Singapore, I spent six days visiting friends and hearing news reports from back home about people stockpiling food, hoarding toilet paper and fights breaking out in liquor stores over bottles of wine. The NBA season was postponed, and the NHL was considering postponing their season as well. European football matches were beginning to take place behind closed doors. Signs were up around the city reminding people to wash their hands, but the malls and the hawkers in Singapore were still operating.

I flew to Jakarta hoping for one last jaunt through South East Asia before moving on to Australia where I would be back in the familiar, English-speaking, territory of the Commonwealth after five months in Asia and Africa. I was always taking things one day at a time but had mapped out a relative idea of my route over the next two months before eventually crossing the Pacific to the Americas and completing my trip around the world. But in less than a week everything would change.

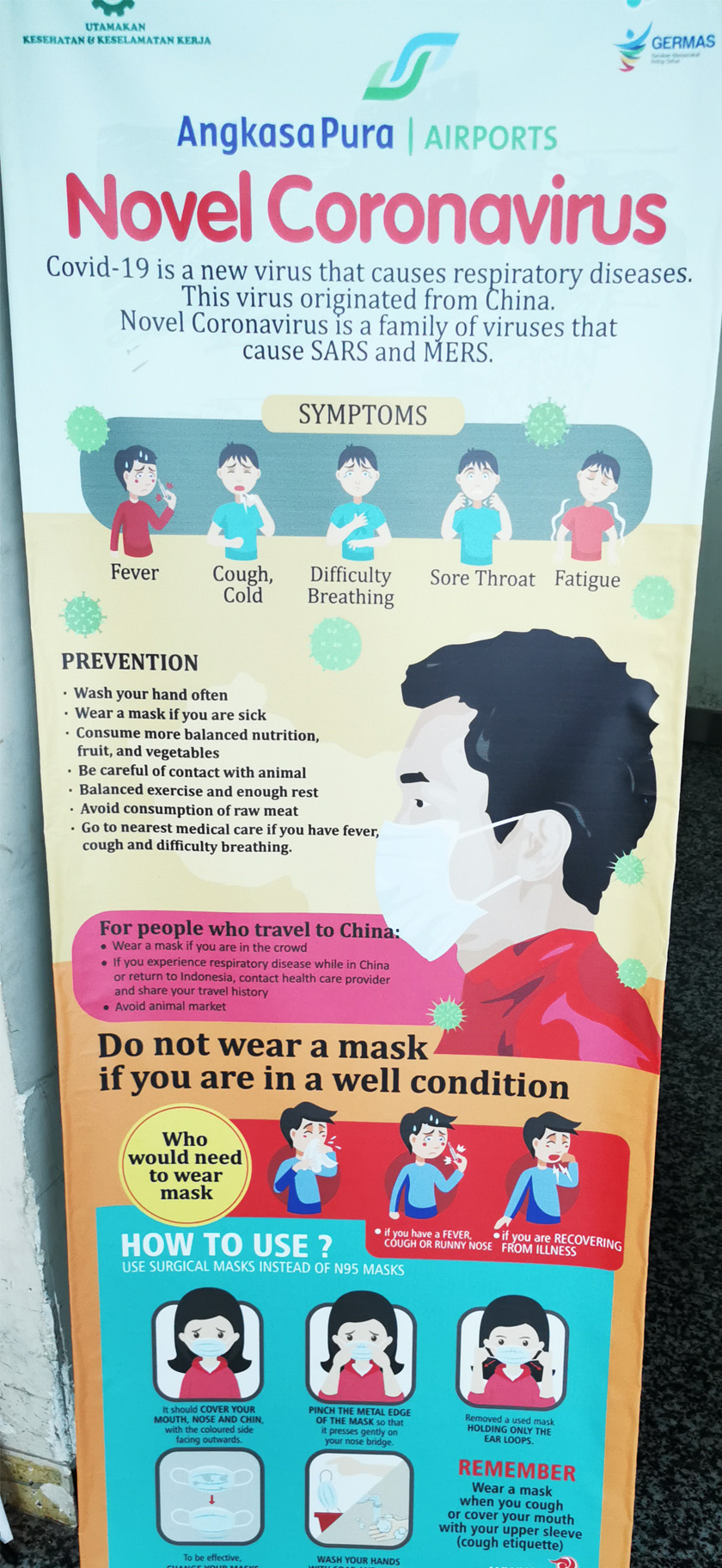

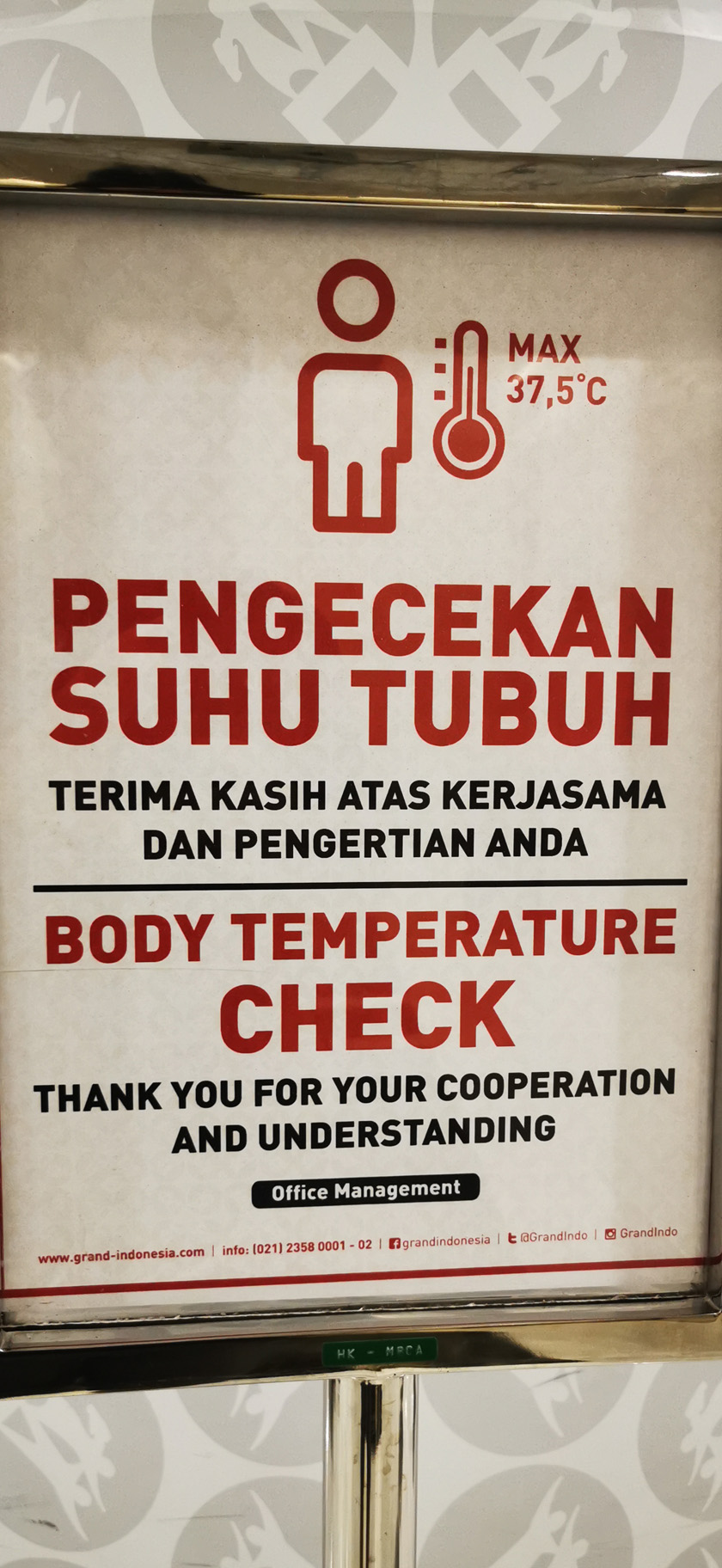

When I arrived in Jakarta, there were the now routine health declaration cards to fill out as well as the temperature scan upon arrival at the terminal. Shopping malls had security guards doing double duty of checking bags and reading temperatures. Advisories to wash hands and to help slow the spread of the virus were on banners and posters throughout the city and in every public washroom. There was hand sanitizer in every elevator, at every hotel reception, and at every grocery store checkout. I was now having daily check-ins with my mother back in Canada about the latest reports and advisories from the government and Canadians were being advised to reconsider their travel plans. Australia had begun to implement targeted travel restrictions. But as I had not travelled to China, Iran or Italy, everything was still business as usual.

Mitigating the spread of the virus is a complex matter, but many of the protocols put in place in several places in South East Asia seemed to do an effective job of flattening the curve while keeping businesses open. From Left to Right: 1) Detailed information on signs in airports and public places of all kinds were widespread in cities throughout South East Asia as early as late January. 2) In Yogyakarta, an employee is subjected to a temperature screening before they are allowed to work. 3) From a shopping mall in Jakarta: a notice to shoppers that they will be subjected to a temperature screening before they will be allowed to enter the mall.

I left Jakarta hoping to make the overland route across Java and eventually cross over on the ferry to Bali where I had planned to laze around for a week or so before catching a cheap flight to Perth, Australia. My first stop was Yogyakarta. By now tourism had slowed and hotel rooms were being given away on the cheap. Canadians abroad were summoned home by the government and I had to remind everyone that my situation was different as I was not on holiday and that, as long as I could travel, nothing really needed to change. I still figured I could get to Australia, or at worst, a safe port where I could stay several months and ride out the storm that seemed to be coming but was still some way off in the distance. I was getting set to move on from Yogyakarta when Australia tightened their restrictions and implemented a 14-day quarantine period for anyone arriving from overseas no matter where they arrived from. I took the train from Yogyakarta to Surabaya and began to rethink my route. It would be an inconvenience, but I could tolerate a 14-day isolation period in Australia to keep this all going, but I was beginning to investigate alternatives. Fiji allowed Canadians to stay up to 4 months which I figured was enough time to see things begin to take a positive turn, and I was tracking a flight that could get me there for about two hundred bucks, so I started looking into housing options.

The next day, Australia closed its borders to all foreign travellers. I decided that enough was enough and that I would head to Fiji at the end of the month. I dilly-dallied on whether or not to buy the ticket I had been tracking and then, after taking a long walk to clear my head, eventually decided to bite the bullet and told myself that this was my best option. I would be arriving in the South Pacific earlier than expected and probably be staying longer than expected but, given the circumstances, it was the sanest solution. When I was redirected to the airline’s website there was no option to buy the ticket I had been tracking, there was just a notice that the airline would be suspending operations in a few days because of the virus. There was only one other opportunity to get to Fiji with a flight leaving in two days. It was one hundred dollars more expensive but, in the ultimate scheme of things, it was a bargain-basement price for any Canadian hoping to go to Fiji – so, I bought the ticket. It now meant, however, that my overland route through Java was over and I hopped on a flight the next day from Surabaya to Denpasar.

In Denpasar, I spent one quiet night out in Sanur before heading to the airport the following evening. This was my moment. Fleeing Indonesia to the safe harbour in Fiji where I could just plant myself down and let the days go by until all of this insanity would finally blow over. I arrived at the check-in counter to collect my boarding pass and was refused because my itinerary went through Sydney. Unbeknownst to me, the day prior, Australia had closed its doors to transit passengers with the exception of those travelling on to New Zealand or to South Pacific Islands and, in those cases, only if they held passports from any of those countries. Reality began to set in and I began to notice what was happening in the airport beyond the narrow six feet in front of my own face. I discovered that I was not alone. A couple, faces red with anger, were yelling at a solemn-looking check-in agent who had refused them boarding passes. A young girl, drenched in tears, was sobbing into her cell phone speaking with loved ones from back home, hands trembling, uncertain of what to do. It was now 9 pm and I had an unused plane ticket hanging in the air, no place to stay, and no idea of where I was going to go or how I would even get there. But there was still time, so I went to a hotel near the airport where I settled in for the evening to work it all out.

The big issue was my visa in Indonesia was only valid for 30 days. There were rumours of some countries extending clemency to trapped travellers who overstayed their visas, but this was a scenario I did not want to test. I had to find out which airlines were still flying, which airports would allow transit passengers, and where Canadians could go for extended periods. I flirted with the idea of returning to Vietnam, but they had suspended their visas to foreigners. I continued to look into Fiji, but there was no affordable way to get there without transiting through Australia which I could not do. New Zealand was also completely closed off. It was the same situation in the Philippines. After much deliberation, as I saw it, the only place where I could reasonably stay long-term and not face fines or jail time was Canada. It was rumoured that Singapore was allowing transit passengers but that passengers staying in Singapore needed to be nationals and would need to undergo a 14-day quarantine. I found a way to get from Singapore to Vancouver via Taipei (who were also allowing passengers to transit) at an affordable price, but it would mean having to avoid Singapore’s terminal 4.

Singapore’s Changi Airport has the distinction of winning Skytrax’s Airport of the Year honours for seven consecutive years – an honour it retains today – and is one of the largest transport hubs in all of South East Asia. Terminal’s 1, 2 and 3 are linked by a sky train meaning that once someone has passed through security that they can transit freely between terminals which makes it especially convenient for passengers who can speedily reach connecting flights at other terminals. Terminal 4, Singapore Airport’s newest, which opened in 2017, is not accessible by the sky train and requires taking a bus between it and terminal 2. For transiting passengers this means going through immigration and needing to once again clear airport security. In my case, any trip, however brief, through terminal 4 would mean facing quarantine in Singapore and missing my onward flight, or worse, not being allowed to board my flight at all.

My internet browser had never had so many tabs open and I had jotted down a jumble of numbers and notes with arrows and connections that looked like something from a conspiracy theorist’s bedroom wall, but I had it. All the dominoes lined up. The route was going to be a nightmare no matter what as there were no direct routes from Bali to Canada, but I could survive 36 hours in various seats on planes and airports around Asia, and, at a mere $650, I would be able to get home for a bargain as I had always been able to do throughout my trip. That was how my brain worked at the time: do the research, get the information, plan the route, find the most affordable alternative, execute. It was not yet midnight and I had all of my virtual tickets so, after emotionally scarfing down a burger and fries, I could rest easy for at least a while.

* * *

Tyler was working on having his Jetstar flight from the previous evening refunded. We had spoken briefly that night during all of the chaos as groups of waylaid passengers shared information about rumours they had heard from airline staff members about which countries were still open and which airlines were still flying. It was just past noon and my flight was not until 10 pm but I was anxious to get my boarding passes to be assured that I would be on my way, but I was told that I would not be allowed to check-in until 3 hours before the flight. As we had received the same information about Singapore, Tyler by now had arranged to fly home via Singapore to San Francisco.

With hours to kill, we sat down at one of the cafés just outside the terminal and I asked him about his own exodus story. He had been travelling for 4 months, hopping around Europe and South East Asia, spending most of his time in Germany and Thailand, as well as the last month in Indonesia – most of it in Bali – and had hoped to keep travelling for some more months before this whole crisis had brought his plans to a screeching halt. Like me, he was concerned about his visa expiring in-country and, as he was unable to obtain boarding passes for his flights the night before for the same reason as I, he was now overdue by a day. We took turns watching each other’s bags while the other went to the toilet and walked around the airport to kill time. We would make periodic stops to check the big board to see which flights were coming up cancelled and watching the check-in lines that were thinning as the customer service lines grew. Disappointed passengers would occasionally emerge from the terminal in a huff, or crying, having to start over and find a solution on how to get home. With so much time spent waiting, it was a good opportunity to get work done, but impossible to concentrate. Minutes felt like hours as we waited for our check-in time to arrive, with sweat dripping from our brows in the suffocating heat of the afternoon in Denpasar as we struggled to find distractions that could occupy our time and make the day seem to pass more quickly.

Monitoring the Big Boards at airports became an obsession in the hours leading up to flights and connections. Cancellations based on new government policies aimed at curbing the spread of the virus were common and would spring up suddenly.

When the early evening arrived, even without an appetite, to sit at one of the airport restaurants and have supper just seemed like something to do to eat up some time until check-in. The waitress kept circling around us hoping to take our order as we slowly perused the menu both to kill time as well as get over the mental hurdle of any plate here costing ten times what the same meal would be in downtown Denpasar. I overheard a girl on the telephone talking with her family about her upcoming flight plan with her final destination in Minnesota. When I noticed that she had finished her call I spoke up:

“Normally I would never do this,” I began, “and I’m so sorry for eavesdropping, but did you just say on your call that you are headed to the US via Australia?”

“Yes, that’s right,” she replied.

“I don’t think they are going to let you on that flight. My friend and I here tried transiting through Australia last night and that’s why we’re here today. I mean, do your own due diligence, but that’s the situation we’re in right now.”

The blood rushed from her cheeks and her heart sank. Others in the restaurant who had overheard our conversation chimed in to confirm what I had been telling her. This was how we met Abbey. Abbey had managed to get boarding passes for a different flight itinerary the night before but had been stopped at immigration as she was required to pay a fine of 3 million rupiah for overstaying her visa. Because she had planned on leaving the country she had no more cash with her, and when she went to the ATM to withdraw money to pay the fine there was a withdrawal limit of 2.5 million leaving her 500,000 rupiah (about $30 US) short. She tried tears to get through immigration, but her flight left without her. Missing her flights a second day in a row was not an option and, upon getting the news about Australia from us, she quickly went into problem-solving mode. She decided that following Tyler’s route through Singapore could get her to the US where she could then find a domestic flight to get her the rest of the way.

Tony and Veronique were sitting just a couple of tables down, sipping beers and watching the time go by waiting for their own check-in times and had overheard our conversation. Everyone initially mistook them for a couple but the truth was that they had only met a few hours ago, both with similar stories and both headed back to Europe – Tony to England and Veronique to France – with still uncertain routes but a flight that night out of Denpasar to Dubai. Both had had their original flight plans upturned the night before because of a transiting issue or a flight cancellation. They were each facing a twenty-four-hour layover in Dubai, before connecting to London, where they would not be allowed to leave the airport. Because of the high number of cases in nearby Iran, rumours were beginning to circulate that Dubai might close its doors altogether and both were eager just to get back to Europe before that happened. Veronique continued to describe her road ahead and welled up with tears when she had to think about the fact that she would be able to get to London but still did not know how she would be able to get home to Nice in the south of France. Local carriers were grounded and the tunnel to Calais was allegedly closed.

A makeshift forum was formed as other travellers shared their stories of how they had gotten stuck in Denpasar and the itineraries they had been forced to devise in order to get home.

“You know that we are the lucky ones,” Tony said. With the prospect of up to 72 hours of continuous travel, dramatically shifting time zones, skipped meals, and naps on airport floors bearing down on all of us, it was difficult to see how we were lucky. “I know we’re all heading into traveller’s hell right now,” Tony continued, “but there will be a time where each one of us will be safe and snug in a familiar bed and we will sleep a sleep so deep and restorative it will make newborns jealous. All of those we know from back home will be ordered to shelter in place, their lives completely disrupted by this fiasco, but we will always have this story to tell. None of us will ever forget where we were when this decision was forced on us, nor will we forget what we needed to summon within ourselves in order to get home to those we love. For that, we are the lucky ones.”

It was time. JQ116 had updated its status and was ready to check in. We shuffled through security and temperature check in order to enter the terminal – the first hurdle passed. The second was the dreaded check-in counter. They were the ultimate gatekeepers of our futures and no one could feel certain about anything until they had their boarding passes in hand. Ladies first, we sent Abbey to the front with Tyler close behind, and both looked at me and smiled as they collected their boarding passes indicating that they’d wait for me before going through security and immigration.

My turn.

“Where are you going today, sir?” the agent asked.

“My final destination is Vancouver, Canada. But the flight I’m taking from here is to Singapore.”

Each clickity-clack sound of the keyboard as she typed my information into the system rang out in my ears as all of the other noises of the airport were completely filtered out.

“I’m sorry, sir, but I can’t issue you a boarding pass for this flight.”

I was near fainting. How could this be? I had done the research, it had all been worked out. If I could not get back to Canada this way, how could I get back to Canada at all? How could anyone? I stepped away from the desk momentarily to wave at Tyler and Abbey and motioned to them that they should proceed onward without me. Their demeanours turned to shock as they threw their hands in the air curious to know why my boarding pass was being withheld, but now was not the time for commiseration. I had to focus on the most immediate problem.

“I don’t understand. What’s the problem?” I asked.

“It’s your onward flight from Singapore, sir. It’s because it is with China Airlines. China Airlines is not a partner with Jetstar. Because they are not a partner airline we cannot guarantee that you will not have to travel through immigration and if you have to travel through immigration you will need to undergo a 14-day quarantine period in Singapore. And if travellers need to go through immigration and be quarantined, then this is only for citizens of Singapore.”

“But the people before me had onward flights from Singapore and they were given boarding passes.”

“Yes, but their onward flights were with a Jetstar partner airline. What you would need to do is purchase a ticket from Singapore to your destination and make sure it is with a partner of Jetstar. That way I could combine your tickets into one itinerary.”

“Is that the only way?”

“I’m sorry, sir, but I think it is the best way.”

Our speaking tones lowered into whispers. The agent motioned me over to the side, showing me a list of partner airlines on her phone and said, “Stay right there next to me, get your ticket, come right back when you’re ready and I will help you out.”

Air Canada was listed as a partner airline and by now the time for half measures and penny pinching was long gone. My hands were shaking nervously as I typed in a search for flights heading from Singapore to Vancouver. With Singapore set to completely close its doors tomorrow at midnight, I had to be on that flight. No more cancellations, no more refunds. My search brought up one flight via Tokyo. The cost was five times that of the China Airlines flight but, travelling with a partnered airline, I could get home. This was what credit cards were designed for and, within a few minutes, I had a new ticket and a new itinerary.

The agent was now helping a couple from Moscow with the same problem as I. The back and forth went on for several minutes as the couple argued their case that they should be allowed to board the flight. The common language was English but neither the couple from Russia nor the local Indonesian Jetstar agent spoke English very well and I could tell that the argument was turning circular and that they were getting caught in a loop. The clock was ticking and I could not let this go on forever. I found an opportunity to intervene and explained to the couple that I had had the same problem and explained what I had just done to solve the problem. The agent showed them the same list of partner airlines she had shown me so that they could get new tickets to their destination.

The agent and I looked deep into each other’s eyes. With her mask covering the core of her expression, her eyes gave away the quivering lips underneath as she put her face into her hands. “It’s so difficult,” she shuddered. “I have had to do that too many times today, but it’s not my fault. It’s the policies of the airlines.”

I showed her the information for my new itinerary and she put it into the system. By now we had an understanding. “Do you have any checked bags, sir?” she asked.

“I have my rucksack here, but normally I take it as a carry-on.”

“Ok, I won’t weigh it,” she said. “I trust you. Here is your boarding pass. You will need to get boarding passes for your other flights when you are in Singapore. Good luck.”

Over the years I have become accustomed to an increasingly automated world where even the humans cannot wrest themselves away from their strict adherence to a decision tree but, on this one occasion, instead of only hearing ‘I’m sorry sir, there’s nothing I can do’ repeated over and over again, this young woman fully demonstrated her humanity and got the job done. At a time when the world was in desperate need of more people who could solve problems, she kept a clear head and helped to rescue at least one poor stranded soul.

* * *

I arrived in Vancouver at the stroke of noon on the 23rd of March a full seven weeks after my visit to the hospital in Bangkok back when the deadly virus that would dominate the lives of everyone around the globe had still just been a whisper. After more than sixteen hours of sleepless flights and ten hours worth of layovers, by the time I arrived in Canada I was groggy and confused but even I felt it a cruel irony to be reporting to immigration using a computerized touchscreen. They were a sign of modernity meant to speed things up and make immigration processing more efficient, but given the current circumstances, as I contemplated how many people had been putting their grimy hands on the screen before me, it did not seem like the most sensible solution. I entered Canada and no one bothered to take my temperature which seemed odd as by then I had become accustomed to having my temperature taken several times a day. Walking through the terminal, border agents were calling out asking if anybody felt sick. We were handed literature about how to avoid spreading the virus and, as returnees to Canada, we were being asked to completely self-isolate for the next 14 days. Restaurants, bars, and retail shops were all closed. Only grocery stores and pharmacies were open and limiting the number of shoppers who could enter. The streets were empty. Traffic was non-existent. The response to the spread of the virus in Canada stood in sharp contrast to the response I had seen in Asia. Canada was approaching 1500 cases and had reported 19 deaths.

Before reaching Canadian shores, I did manage to catch up with Abbey and Tyler. We banded together at Changi airport and worked together to get the information we needed to get ourselves on our connecting flights. It was 2 am the next day in Singapore and we all had long roads ahead and, eventually, it was time to part company which we conspicuously observed through the now disappearing time-honoured tradition of shaking hands.

My flight to Japan was on a huge jet designed to fit upwards of 350 people, but there were perhaps only 40 on board. My internal clock was all messed up but the local time was indicating that it was the early afternoon and Tokyo-Narita Airport was eerily quiet. I was unable to sleep and unable to concentrate on anything. Flight attendants no longer bothered complying with FCC regulations dispensing with the customary pre-flight safety demonstrations. In-flight services were conducted swiftly and from behind a mask through eyes without a smile. Crew and passengers all seemed to be on the same page: get in the air, land safely, go home and stay there.

My taxi driver from the airport pointed out that times were getting tough economically in Vancouver and that I would probably be his only fare that day. He had been earning next to nothing for weeks, but next to nothing was still at least something. My mother was waiting by the front door of my apartment building waiting to throw me the keys so that I could get to the safety of my old space and finally have some well-deserved rest. I had not seen her for months and I swore then that the government’s insistence to keep 2 meters between her and her child would be asking too much, but even she kept her distance. Two days earlier I had woken up under the sun-drenched skies of Bali after 10 consecutive months chasing sunshine and warm weather around the globe. Now, to be back in Canada in the first days of spring, I was hit by the cold grey reality that the world had become a bleak and distant place. I know that this storm will pass and that my mother and I will again share warm comforting hugs that remind us that the world is not always so cruel and frightening, but, for now, they would have to wait. As for my travels and chasing sunshine, those great cities and exotic lands that stretch to every corner of this amazing planet will find a way to rise above this challenge and undoubtedly draw me to their shores. But will we ever be the same?