Wari

Ch’Ikidikan descended from the mountain and wept. He had passed through the Qu’Uatlhayna and the Chuk’Okuano and gazed upon the rocky plain that, as stories foretold, stretched on as far as man could walk before they laid their eyes upon the endless salt-water sea and died.

Tales of the stone steppe, the I’Hywalla, had been passed down from generation to generation. The I’Hywalla had been the fabled final home of The Good before they set across the sea forever. When Ch’Ikidikan arrived, pilgrims from tribes as far south as the At’Kam and as far north as Ayt’Kaytatan had gathered to make The Call. It was clear that Ch’Ikidikan had arrived for the same purpose as the other pilgrims and he was immediately offered water and shade – the two scarcest and most sacred resources on the steppe. All of them understood. All of them had descended upon the steppe to continue The Call and then to die.

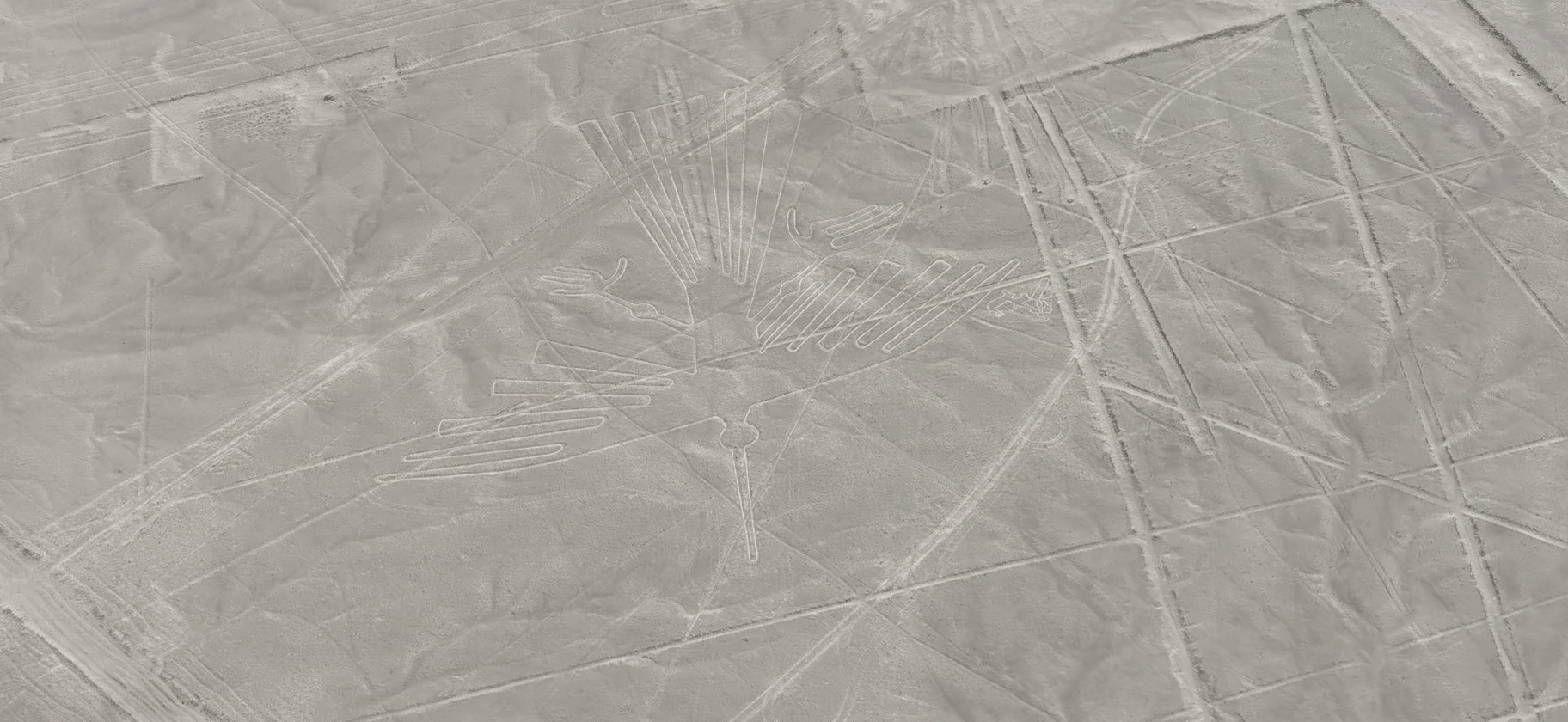

Nothing survived in the I’Hywalla. Stones scattered across the steppe, rising from the sand, like a mirror to the stars in the sky. They were the only light in the dark of night as there was no wood to burn to make a fire.

“I am Tepu’Hekel,” the tallest warrior Ch’Ikidikan had ever laid eyes on said to him. “Rest here by the tallest stone. You have come a long way and there is much work to be done.”

“I understand your words,” Ch’Ikidikan replied with surprise.

“You bear the mark of Wari,” he replied. “Your people took the lands of our mountain when I was just a boy. My mother was spared and we were adopted by the Par’Hacaz, the people who grow their heads long to remember. I know your people. I learned the tongue and I was taught never to forget.”

“I would have also been just a boy when my people invaded your villages. I ask not for forgiveness but take a stone and crush me as repayment of this debt.”

“Your people sent the right man. We need good men here. Make The Call to The Good until you die and consider your peoples’ debt repaid.”

Ch’Ikidikan nodded with understanding, shivered with cold in the fading light, and went to sleep.

The pilgrims set to work the moment the dawn came. They would have charted a path using the stars from the previous night as their guide. Together they set out from the steppe to find free stones and soft rock to quarry with their axes.

Tepu’Hekel was the strongest but all followed the orders of Ik’Hanniha the oldest of those now living on the steppe. Ik’Hanniha was Mo’ahochay and, by his appearance alone, seemed a silly choice for his tribe to send to the steppe. To Ch’Ikidikan, he seemed the oldest man that had ever lived. His hair had greyed from the passing of time and his skin had wrinkled like ripples of the wind on water. The piercings on his chest hung over his swollen belly and his lips drooped to his chin. His knees could not bend and his feet moved slowly. On any hunt, he would have been left behind. But he had descended from the mountain like all the rest who were there and the journey itself kills many that appear stronger and more worthy.

“You must find your heart-stone,” Ik’Hanniha told Ch’Ikidikan. “This is mine.”

Upon Ik’Hanniha’s heart-stone were markings to which he pointed with pride. “What do they mean?” Ch’Ikidikan asked.

“They represent those whose bones have been walked to the sea since I came to the steppe. Thirty-nine in all. Because you are the next to come here, when the next of us dies, we will feast but then you must walk the man’s bones to the sea. You will walk the bones to the sea if you live.”

“Nobody returns from the sea.”

“Nobody returns home.”

Ch’Ikidikan gathered a stone, the largest that he could carry, from the base of the mountain and placed it alongside the others in the dying lands on the edge of the steppe. He carved his symbol and that of his tribe into the flat face of the rock and, unlike the others, he laid it face down so it would not be touched by the wind. The other pilgrims watched him perform his initiation curiously. When he had placed his stone he turned to them, placed his left hand on his chest and said, “Travel well”.

Ch’Ikidikan gathered a stone, the largest that he could carry, from the base of the mountain and placed it alongside the others in the dying lands on the edge of the steppe. He carved his symbol and that of his tribe into the flat face of the rock and, unlike the others, he laid it face down so it would not be touched by the wind. The other pilgrims watched him perform his initiation curiously. When he had placed his stone he turned to them, placed his left hand on his chest and said, “Travel well”.

“Travel well,” the pilgrims repeated together.

Ik’Hanniha approached Ch’Ikidikan and said: “You chose a good stone. But remember that tomorrow you choose a stone for The Call.”

Ch’Ikidikan nodded.

Ik’Hanniha asked: “Why did you lie your heart-stone over on its face? The sun will not see your mark.”

“I heard a voice that said that this is what I should do. So, this is what I did.”

“You hear the voices?” Ik’Hanniha asked.

“I do. Sometimes I do.”

“I also hear the voices.”

“Are we blessed by The Good?” Ch’Ikidikan asked.

“Perhaps. Perhaps we are cursed. But you are the first pilgrim that I have met who also hears the voices. Does your tribe know?”

“Yes.”

“Is that why they sent you?”

“My tribe did not send me. One day the voices said that I should leave to make The Call. So, I left.”

Ik’Hanniha, placing his left hand on his chest, said: “Travel well”.

Four days passed, each with the same routine of plotting the stars from the night to steady the path for the next morning. The pilgrims travelled to the new quarry, pulled a stone, and hauled it back to the steppe. Ik’Hanniha alone no longer made the march, but according to his orders, they placed their rock on the sand adding them to The Call.

On the fifth day, during their march to their quarry, Tepu’Hekel stopped them.

“Do you feel it?” he asked. The pilgrims looked at the great warrior with curiosity.

Tepu’Hekel closed his eyes and raised his head as high into the wind as he could.

“You smell blood?” one of the pilgrims asked.

“I do,” Tepu’Hekel replied.

“We cannot take ourselves off the march,” one of the pilgrims challenged. “The Call is our task”.

“One drop of blood may keep us for many days,” Tepu’Hekel replied. “It is the blood of all the land that makes The Call. As servants to the land, it is our duty to sustain.”

“Some of us do not have many days left,” said another pilgrim. “Our blood will sustain the others.”

“Continue to the quarry,” Tepu’Hekel replied. “I will go alone. Blood and bones will be my stone for this day.”

“I will come with you,” Ch’Ikidikan offered. “If blood and bone of the beast are to be our treasure, even a warrior as strong as you will fall under the weight of vik’wuna.”

Together Ch’Ikidikan and Tepu’Hekel left the group following the scent of blood winding through the hills. A haze rose over the plain as the hours passed under the hot sun.

“Does the scent grow stronger?” Ch’Ikidikan asked.

“Does the scent grow stronger?” Ch’Ikidikan asked.

“No,” Tepu’Hekel replied. “I fear that our prize may already have been picked apart by the birds.”

“We have walked too far and there is no blood. We will not be able to return to the camp before nightfall.”

“No.”

“We should return.”

“No. If I cannot find blood, then I will make blood.”

Tepu’Hekel pointed off into the distance beyond where Ch’Ikidikan could see.

“What do you see?”

“Vik’wuna. A herd.”

“They are too swift and we are too few. We cannot hunt.”

“Then we must pray that the blood is there waiting.”

“And if not,” Ch’Ikidikan asked.

“Then one of us will be the blood.”

From the haze, small grasses pushed through the sand. Vik’wuna slowly and deliberately, with noses to the ground, pulled the ripest of the leafy fruit making the grasses hungry for more of the moist air. They dined in peace until the moment that they were drawn to the presence of Ch’Ikidikan and Tepu’Hekel’s feet scraping along the sand. Pulling their necks from the ground, in perfect unison, the whole of the herd darted off into the distance pushing sand into the air and stirring the wind enough to cut through the heavy haze that pushes all to the earth.

“This way,” Tepu’Hekel, with his nose in the air, said pulling Ch’Ikidikan by the arm.

In a moment, the blood was revealed. A young vik’wuna had collapsed on its journey to the grasses.

“The Good have saved us,” Ch’Ikidikan said choking on his breath and looking to the sky.

“Vultures will be upon us,” Tepu’Hekel said. “We must be quick.”

Grabbing at two loose stones resting in the sand, Tepu’Hekel smashed them together and cut the neck of the animal to end its suffering.

“Drink,” he ordered Ch’Ikidikan. Using the stone blade, he cut off the head of the animal. With a snap, he broke off the forelegs and, with the head, handed them to Ch’Ikidikan. He bent down and hoisted the whole of the hind of the animal onto his shoulders. “Come, we walk through the night. The stars will lead the way.”

Upon their return, the pilgrims feasted on meat they had not tasted since they had left their homes in the mountains. Ik’Hanniha was offered the liver which he declined while smiling at Ch’Ikidikan.

“You know what is to come,” he said. “I am only sorry that I am so old. My flesh will be dry like eating the sand.” Ik’Hanniha laughed.

Five days passed. Reading the stars, Ik’Hanniha told the pilgrims that the next morning he would go with them on their journey to the quarry. Hours marching in the blaze of the day sun, Ik’Hanniha pulled a stone perfectly formed and so great in size that the pilgrims did not believe he could carry it.

“It is a strange magic the old man wields,” said one pilgrim marvelling at the Ik’Hanniha’s strength.

“I may be old, but my hearing is sharp,” Ik’Hanniha cried out overhearing the whispers of the group of pilgrims. “And it is not magic. It is a knowledge that our people have lost. Someday it will be gone. It is why we make The Call.”

They placed their stones with care upon the steppe and rested underneath the stars. Tepu’Hekel again smelled blood. He approached Ik’Hanniha, placed his right hand upon his chest and said: “Travel well.”

By the morning, Ik’Hanniha’s spirit had left his body. Lifted by his wisdom to the hallowed lands of The Good, his heart stone stands today as a monument on the edge of the steppe eroded by time and the sand left for generations of the forgotten. His contribution to The Call was at an end.

The flesh was torn from his bones and consumed by the pilgrims left on the steppe to perform their duty.

“Travel well,” the pilgrims cried out to Ch’Ikidikan as he left the camp tasked with transporting Ik’Hanniha’s bones to the sea.

For two days, Ch’Ikidikan followed the falling sun to the edge of the salt-water sea. Bending to his knees in the soft sand, he placed Ik’Hanniha’s bones next to him as waves crawled gently up the shore. He pulled the sand from all directions to form a pyramid. It was what the voices told him to do. When he was finished, he looked down at what he had built. He waited by the shore until the night came so that he could look up to the sky to make sure that his pyramid aligned correctly with the shape of the stars. When he was certain of its symmetry he tossed Ik’Hanniha’s bones into the sea. His oath fulfilled, Ch’Ikidikan walked up from the shore and formed a nest in the sand where he could fall asleep.

When the morning came, Ch’Ikidikan walked to the shoreline where the waves had washed away his pyramid of sand. He looked out to the horizon, placed his left hand on his chest and said, “Travel well”, and then continued his journey back to the steppe.

Along the way, Ch’Ikidikan thought about all of the things that had been lost. In his veins, he could sense that the centuries of knowledge, passed from fathers and mothers to their children, were disintegrating. One day, he decided to leave his wife, his children, and his entire village because that is what the voices told him that he should do. He alone of his generation and of his tribe could hear the voices. As a boy, he remembered a council of elders who all heard the voices. They were the most trusted of all of the members of the tribe and understood how to read the stars and align their sacred pyramid. Above all, they respected The Good and The Call. The members of the council had all passed and a new generation had seized the leadership and commanded the direction of the tribe while casually grasping at the fraying threads of their long-held traditions. Whispers of tall men from the north who had learned to harness the powers of the rains in their terraces had reached Ch’Ikidikan’s tribe. One day, they would flood across the mountainside creating a green barrier between the mountain tribes and the sea. They would block the steppe and the light of The Call would be extinguished. All of history is a history of forgetting and every new fact is a restatement of an old idea in a new context. Already the voices were being silenced. The voices spoke to him and urged him to fulfill his duty but, in his heart, Ch’Ikidikan knew that The Good would never hear their call and would never return.

Returning to the steppe, another pilgrim had died so there was blood upon which to feast. Ik’Hanniha’s spirit had gone and there was no one to order that the man’s bones be taken to the sea. Ch’Ikidikan gathered some loose stones to form a pyramid to honour the man’s ghost but the other pilgrims did not seem to understand. Some days later, another pilgrim emerged from the mountains, sent by his tribe, to make The Call. On some days, Tepu’Hekel would walk the plain and return with blood. Ch’Ikidikan continued to read the stars at night but his voice held no authority on the steppe. Some of the longest-serving pilgrims, along with Ch’Ikidikan, followed the stars to the quarries and returned with stones for The Call but, as days passed and old pilgrims died and new pilgrims descended from the mountains, they trusted more in the orphan, Tepu’Hekel’s, keen senses and smell for blood than Ch’Ikidikan’s readings of the stars.

Tepu’Hekel’s taste for blood overtook him and he began to spend more of his time on the steppe on the hunt rather than making The Call.

One day, Ch’Ikidikan told him, “You make more sport than you speak to the heavens. Sport is for young men. We have our duty. Cease your incessant hunting and make The Call.”

“My duty is for us to live,” Tepu’Hekel replied, “so that The Call can be completed. Every drop of blood gives us this chance.”

“Would Ik’Hanniha agree with you?”

“I believe, yes.”

Ch’Ikidikan looked at the great warrior with sadness. He placed his left hand on his chest and said, “Travel well.”

Tepu’Hekel, stoically and mustering equal parts defiance and respect for his brother of the steppe, placed his right hand on his chest and said, “Travel well.”

Histories get rewritten, traditions become lost, and centuries of wisdom are supplanted by the temptation of extended life. Tepu’Hekel continued to gather volunteers to join him on his hunts that became more frequent and far-stretched. So daring became each expedition that some days the hunters would return only with the blood of another pilgrim fallen along the way. K’wechwa, on harvested grain, hearing no voices, plugged the dykes and stemmed the flow of pilgrims to the I’Hywalla. Ch’Ikidikan’s and Tepu’Hekel’s bodies succumbed to the stresses of their respective quests and the shadow of passing time. According to their sense of duty, pilgrims along each path feasted on their flesh using their blood to sustain them but no pyramids were built to honour their sacrifice. The last fern growing on the steppe withered and dried. Vik’wuna, hearing the voices, migrated and found new plains for pasture. The Call became neglected and was eventually abandoned. Stories of The Good vanished from the campfires stretching over every corner of the continent by the sea, mountain and jungle. With no Call reflecting the mirror of stars, knowledge replaced by novel ideas, The Good would never return.