Tales From Tazara

Meeting Ulli

The Tazara Company runs trains from Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania, to Kapiri Mposhi, in Zambia, and back two times a week. The trip is over 1800km and, depending on delays, takes over 50 hours. The route runs more than a 100km south of the main highway between Dar es Salaam and Mbeya cutting through a lot of untamed wilderness and stopping at every small village along the way. There are a number of first and second class sleeper berths as well as almost a dozen cars worth of third class seating filled with locals, some only going a few stops, others going all the way and simply unable to afford a sleeper car. Families tend to occupy whole compartments in second class, while a handful of locals mix with an intrepid set of foreigners in first class. Anyone with a white face sticks out like a sore thumb and the station master typically makes an effort to put foreigners together in the same compartment. Men and women are always separated.

I decided to break up the journey and descended the Kilimanjaro train in Mbeya, in Tanzania, deciding to wait for the Makuba train that would be passing on Friday. Along the way from Dar es Salaam to Kapiri Mposhi, I met all sorts of fascinating people who all had a story to tell. Riding the train in Tanzania is not common for visitors, so everyone passing through has done their share of travelling in the past and the stories they tell are rarely of weeks spent lounging on a sunbed in a resort with the meals and the drinks included. The stories they tell, instead, involve long arduous journeys through places few seldom seek to go, much like the journey we were now on. Between Nick, a Russian-British national, writer and journalist; Marin, a recent university graduate cycling around Africa for the next year and a half; Gift, a local Zambian who had travelled to Dar es Salaam looking for business opportunities; Matthias and Jeska, friends from Poland travelling on from Kapiri Mposhi as far as Livingstone; or Patrick, a local Zambian who came to my rescue when the train arrived after midnight in Kapiri Mposhi, all had a fascinating story to tell. There were stories of nights spent in mansions with servants at the behest of wealthy businessmen in Kigali who were just lonely had nothing better to do but assist couch surfers; stories about subway robberies in Rio de Janeiro; and stories about train and bus routes gone wrong in remote corners of the world. But, no traveller’s stories fascinated me more than Ulli’s.

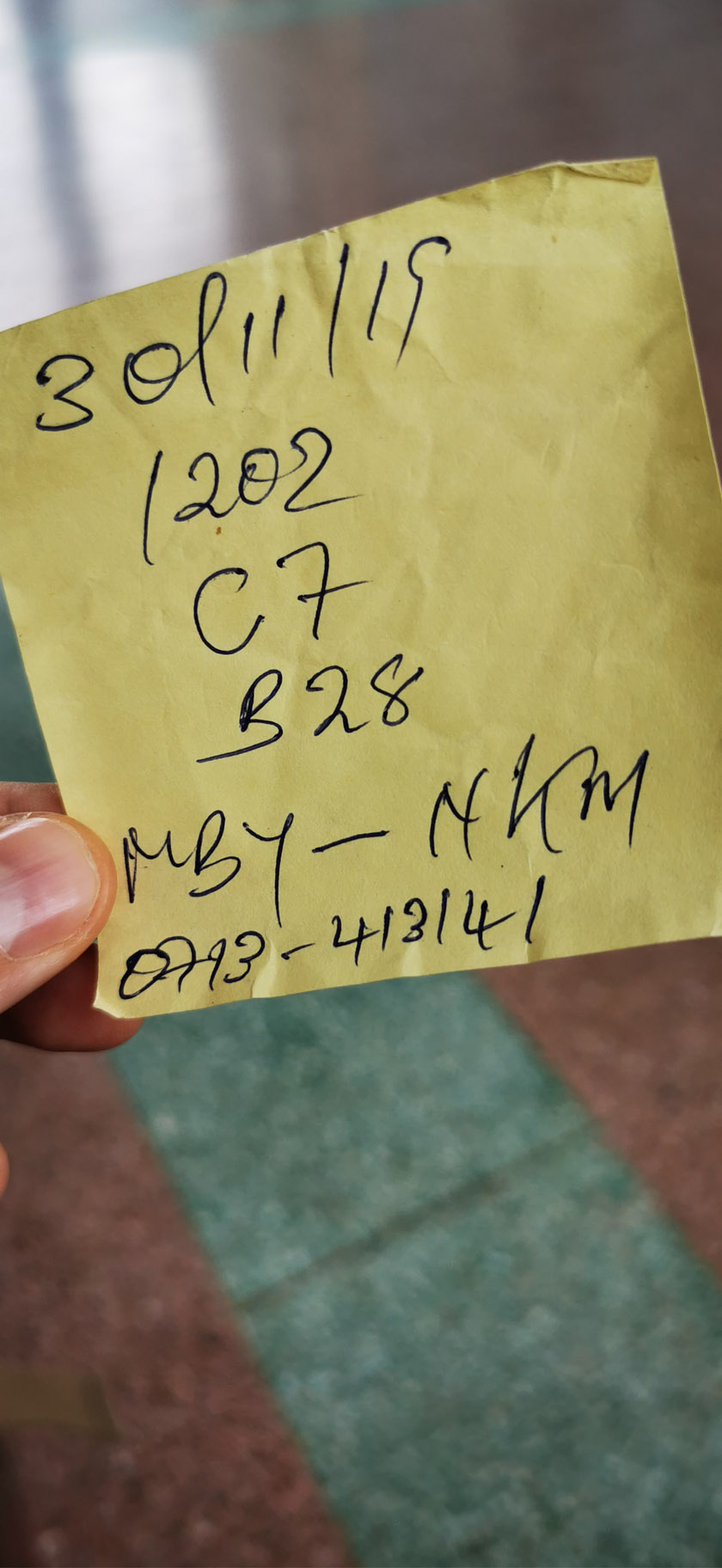

Interestingly, Ulli was the one passenger that I didn’t actually meet on the train. Instead we passed each other at Mbeya station going in opposite directions. Online information about the train is sparse and often inaccurate, but according to the research I had done the train was scheduled to pull through Mbeya around 2 pm. I had, what I was told was a reservation that had been written on a post-it note, but I hadn’t purchased my ticket so I arrived before 11 am hoping to settle things knowing that once I had a ticket my anxieties would subside. There was no one at the booking office and only a few locals sitting around or napping on the benches, and after waiting for an hour I went to ask questions and was told that the booking office would open at 2 pm and that the train was now scheduled to arrive at 4. Anyone with a white face stands out like a sore thumb, and during that wait for the booking office to open was when I met Ulli. Because we both stood out, as happens to a lot of foreigners who travel in the more remote parts of the world, there was an immediate understanding that we were likely searching for the same bits of information, and there was an immediate exchange with each of us asking the other what we knew about the current situation.

Interestingly, Ulli was the one passenger that I didn’t actually meet on the train. Instead we passed each other at Mbeya station going in opposite directions. Online information about the train is sparse and often inaccurate, but according to the research I had done the train was scheduled to pull through Mbeya around 2 pm. I had, what I was told was a reservation that had been written on a post-it note, but I hadn’t purchased my ticket so I arrived before 11 am hoping to settle things knowing that once I had a ticket my anxieties would subside. There was no one at the booking office and only a few locals sitting around or napping on the benches, and after waiting for an hour I went to ask questions and was told that the booking office would open at 2 pm and that the train was now scheduled to arrive at 4. Anyone with a white face stands out like a sore thumb, and during that wait for the booking office to open was when I met Ulli. Because we both stood out, as happens to a lot of foreigners who travel in the more remote parts of the world, there was an immediate understanding that we were likely searching for the same bits of information, and there was an immediate exchange with each of us asking the other what we knew about the current situation.

Ulli was trying to get back to Dar es Salaam as she would be leaving Tanzania in a week and she didn’t have a reservation yet for the train. She was from Austria and had been travelling since the early seventies. Now in her mid-sixties, widowed, and retired, by the time we met she had been all over the world. She had even been to Tanzania 40 years ago and expressed that in all that time there were a few new buildings and cell phones of course, but the people and the landscape really hadn’t changed all that much. She was a semi-professional photographer, and because she wasn’t afraid to go out to remote places, she was able to capture some stunning images from around the world. She and her daughter run a travel blog called Cookie Sound, but for Ulli, all that social media stuff was something she left up to her daughter. For Ulli, it was about being out on the road and seeing and photographing places she had never seen or photographed before. She had a grit and carried herself assuredly as though there was nothing she hadn’t seen before. She had a particular fondness for driving old cars from Europe to Africa and then selling them. She was a remarkable storyteller who had seen and done amazing things, but had a way of beautifully expressing herself making the best use of her rudimentary English vocabulary and her thick Austrian accent. During our 10-hour wait for our respective trains we shared all sorts of stories with each other, but one story in particular that she told stood out among the rest.

Sebastian the Italian Drifter

“It’s amazing, sometimes, the trouble people get themselves into. I had taken the car on the boat from Italy to Morocco and I was travelling through Western Sahara when I found this poor guy at a petrol station with nothing else for miles around and he had nothing, just a guitar. No money. No bags. Just the guitar. He was an Italian. Sebastian was his name. And he wanted to go to Senegal to learn to play the drum. That’s what he said, he wanted to go to Senegal to learn to play the drum. Who knows why? Anyway, so he was in trouble with no way to go anywhere and no way to do anything and I so picked him up and I said I would at least take him to the border or somewhere where he could get help.

“’You want to go to Senegal,’ I said to him. ‘You know that you will have to cross a border. How did you think you would be able to do this without money?’ He just shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘I don’t know’. So he was in a bad situation but I gave him a ride and I paid for a few things here or there while we were travelling to the border because he had nothing. So here I was giving him all this help and he was criticizing the way I was driving saying, ‘you’re going too fast!’ or ‘why aren’t you going faster?’. And then I would stop occasionally to take pictures, you know, when I saw something interesting and he would get upset, ‘why are we stopping?’ he would say with an angry voice. But I couldn’t seem to get through to him that I was happy to help but that this was my car and that he was borrowing my money so I was going to do what I felt like I wanted to do. My life and my travels were not going to stop just for him.

“So, we were approaching the border of Mauritania when I wanted to stop by this sort of gorge by the side of the road to take pictures and sure enough there was a car that had passed us before that had gone off the road and fallen down into the gorge. Two of the passengers were wrapped around the rocks and were long dead, but there was one poor guy who was going to die but was still a little bit alive and crawling around outside of the car. So I told to Sebastian to come with me to help this poor guy. But he was just freaking out. He was like, you know, hysterical. But I had a surfboard and so I took the surfboard down and I was still yelling to Sebastian to help me to make some shade for this poor man who was suffering and was going to die. And we were there for some time and this poor man was suffering, but eventually, a military truck came and the guy was still alive and they said that they would take him to find medical help. I left the surfboard because it was useful to them, but now I could get back on with my travels and I don’t know what happened to this man after. Maybe he survived, but I doubt it.

“Anyway, by this time this Sebastian guy was driving me crazy and when we got to a proper town I got a phone card so that he could call his mother so that he could go home. You know, his mother was so upset because she didn’t know what had happened to her son and they were talking on the phone and they were both crying. And so, I paid for a ticket for this young man to go back home and eventually after some time his mother wired me the money to repay me for my kindness and I suppose he got himself home. And me, eventually I went into Mauritania and I was able to sell the car for, I don’t remember how much, I think it was a thousand euros or something. But I don’t understand who does these kind of things like this Italian guy. Leaving with no money and nothing. You know, you can meet all kinds of crazy people.”